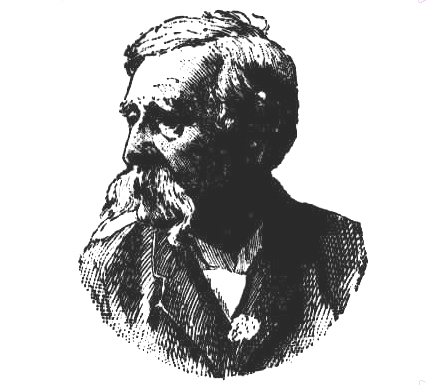

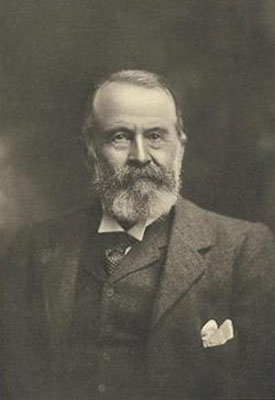

Henry Halloran (1811-1893)

|

She coaxes me on like a siren at play,

Then leaves me alone with a shadow to doze.

As faithless as Venus, she flits with a fay,

Or marries her moods to the rim of a rose.

I went to her house and I opened the door

To peep at the exquisite corridors there,

And thousands of dreams that were strewing the floor

Cried: "Constancy only can win the most fair."

And so on her lily-white doorstep I wait,

Or wander away with her lover in glee.

Now faithful, now fickle, I toy with my Fate,

For I am a maiden as wilful as she.

My Muse, 1917

Zora Cross Wikipedia entry

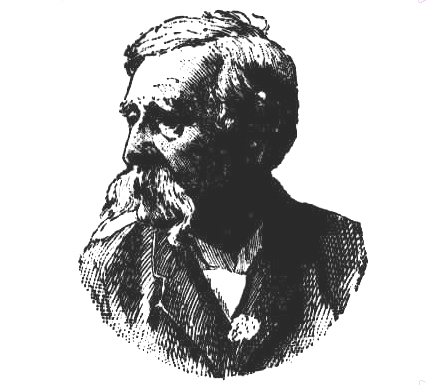

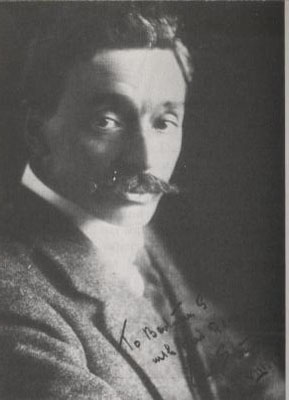

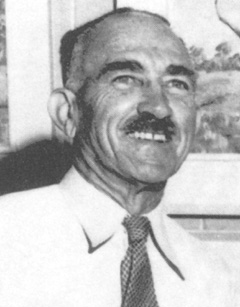

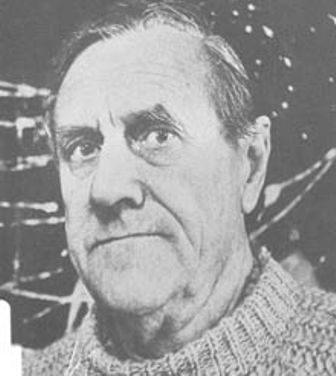

Norman Lindsay (1879 - 1969)

"You have solved the problem," said Bunyip Bluegum, and, wringing his friend's hand, he ran straight home, took his Uncle's walking-stick, and, assuming an air of pleasure, set off to see the world.

He found a great many things to see, such as dandelions, and ants, and traction engines, and bolting horses, and furniture being removed, besides being kept busy raising his hat, and passing the time of day with people on the road, for he was a very well-bred young fellow, polite in his manners, graceful in his attitudes, and able to converse on a great variety of subjects, having read all the best Australian poets.

Unfortunately, in the hurry of leaving home, he had forgotten to provide himself with food, and at lunch time found himself attacked by the pangs of hunger.

"Dear me," he said, "I feel quite faint. I had no idea that one's stomach was so important. I have everything I require, except food; but without food everything is rather less than nothing.

"Ive got a stick to walk with.As he was indulging in these melancholy reflections he came round a bend in the road, and discovered two people in the very act of having lunch. These people were none other than Bill Barnacle, the sailor, and his friend, Sam Sawnoff, the penguin bold.

I've got a mind to think with.

I've got a voice to talk with.

I've got an eye to wink with.

I've got lots of teeth to eat with,

A brand new hat to bow with,

A pair of fists to beat with,

A rage to have a row with.

No joy it brings

To have indeed

A lot of things

One does not need.

Observe my doleful plight.

For here am I without a crumb

To satisfy a raging tum --

O what an oversight!"

From The Magic Pudding by Norman Lindsay, 1918

|  |

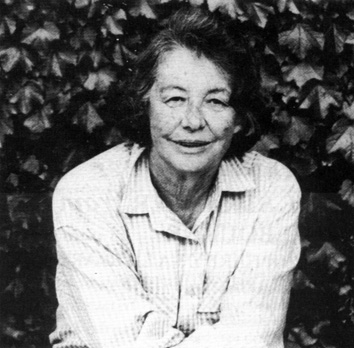

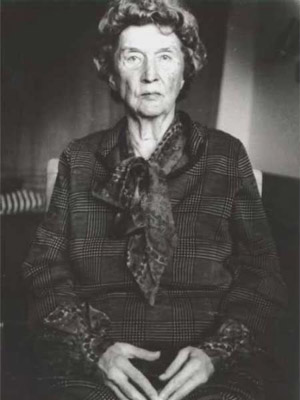

Marjorie Barnard (1897 - 1987) and Flora Eldershaw (1897 - 1956)

The first light was welling up in the east. In the west a few stars were dying in the colourless sky. The waking sky was enormous and under it the sleeping earth was enormous too. It was a great platter with one edge tilted up into the light, so that the pattern of hills, dark under a gold dust bloom, was visible. The night had been warm and still, as early autumn nights sometimes are, and with a feeling of transience, of breaking ripeness, of doomed fertility, like a woman who does not show her age but whose beauty will crumble under the first grief or hardship. With the dawn, sheets of thin cold air were slipping over the earth, congealing the warmth into a delicate smoking mist. Knarf was glad to wrap his woollen cloak about him. Standing on the flat roof in the dawn he felt giddily tall and, after a night of intense effort, transparent with fatigue. Weariness was spread evenly through his body. He was supersensitively aware of himself, the tension of his skin nervously tightened by long concentration, the vulnerability of his temples, the frailty of his ribs caging his enlarged heart, the civilisation of his hands . . . Flesh and imagination were blent and equally receptive. The cold air struck his hot forehead with a shock of excitement, he looked out over the wide sculptury of light, darkness, earth, with new wonder. For a few moments turning so suddenly from work to idleness, everything had an exaggerated significance. When he drew his fingers along the balustrade, leaving in the thick moisture faint dark marks on its glimmering whiteness, that, too, seemed like a contact, sharply intimate, with the external world where the rising light was beginning to show trees dark and grass grey with that same dew.

From Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow by M. Bernard Eldershaw, 1947 (censored version), 1983 (complete version)

A bit of explanation is required here: This novel was originally published in 1947 under the title Tomorrow and Tomorrow after the text was censored by the Australian Government. The book's original title, and the censored text, was restored in the Virago Modern Classics edition of 1987. M. Bernard Eldershaw was the pseuodnym used by Marjorie Barnard and Flora Eldershaw. Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow was the fifth novel they wrote together between 1929 and 1947. It was also to be their last. The book is considered to be one of Australia's major early science fiction novels and was named by Patrick White, in the 1980s, as the Australian novel he would most like to see republished.

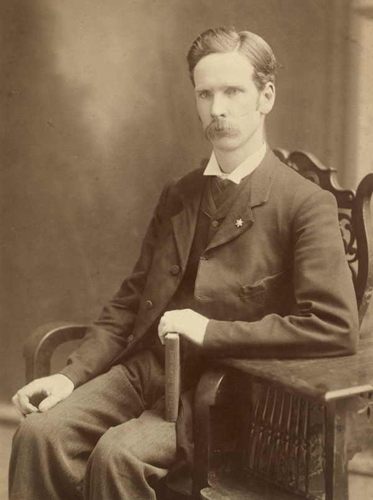

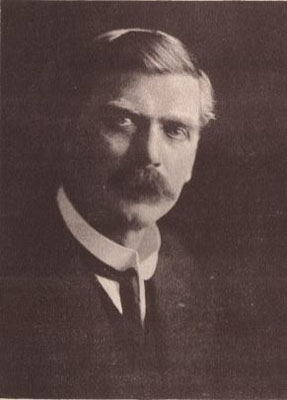

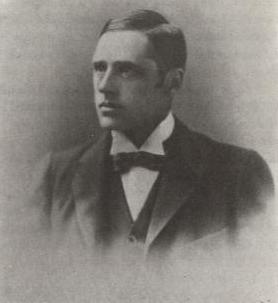

Rolf Boldrewood (1826 - 1915)

My name's Dick Marston, Sydney-side native. I'm twenty-nine years old, six feet in my stocking soles, and thirteen stone weight. Pretty strong and active with it, so they say. I don't want to blow -- not here, any road -- but it takes a good man to put me on my back, or stand up to me with the gloves, or the naked mauleys. I can ride anything -- anything that ever was lapped in horsehide -- swim like a musk-duck, and track like a Myall blackfellow. Most things that a man can do I'm up to, and that's all about it. As I lift myself now I can feel the muscle swell on my arm like a cricket ball, in spite of the -- well, in spite of everything.

The morning sun comes shining through the window bars; and ever since he was up have I been cursing the daylight, cursing myself, and them that brought me into the world. Did I curse mother, and the hour I was born into this miserable life?

Why should I curse the day? Why do I lie here, groaning; yes, crying like a child, and beating my head against the stone floor? I am not mad, though I am shut up in a cell. No. Better for me if I was. But it's all up now; there's no get away this time; and I, Dick Marston, as strong as a bullock, as active as a rock-wallaby, chock-full of life and spirits and health, have been tried for bushranging -- robbery under arms they call it -- and though the blood runs through my veins like the water in the mountain creeks, and every bit of bone and sinew is as sound as the day I was born, I must die on the gallows this day month.

From Robbery Under Arms by Rolf Boldrewood, 1882

|

On a November evening in the middle of the nineteenth century, Mr William Vane, an undergraduate of Clare College, Cambridge, gave a wine party in his rooms. His guests as well as himself had that day ridden to hounds. There had been two kills and they were in high spirits.

A Mr Brayford, of Trinity, while singing a roundelay, let his cigar butt fall on to a spot on the carpet where Mr Vane yesterday had dropped and broken a bottle of scented hair pomade. No one noticed the burning cigar, but Mr Brayford was still sober enough to notice the smell of smouldering wool and smoking perfume.

"Gad!" he exclaimed. "What a stench!" A few minutes later he said" "Gad! I'm going to puke."

Vane had also noticed the smell. Brayford's last remark stimulated a dormant echolalia in his confused and heated brain.

"Gad! It's the Puseyite!" he cried. "The filthy man must be burning incense. Let us wash the filthy man!"

Shouting "No Popery!" -- which expressed in two words the extreme limit of their religious aspiration -- the party trooped down the stairs and burst open the door of the rooms below, which were kept by Aubrey Chapman, a scholarly, slightly asthmatic, mildly High Church undergraduate, who intended to take Holy Orders.

From Lucinda Brayford by Martin Boyd, 1952

Louis Stone (1871 - 1935)

One side of the street glittered like a brilliant eruption with the light from a row of shops; the other, lined with houses, was almost deserted, for the people, drawn like moths by the glare, crowded and jostled under the lights.

It was Saturday night, and Waterloo, by immemorial habit, had flung itself on the shops, bent on plunder. For an hour past a stream of people had flowed from the back streets into Botany Road, where the shops stood in shining rows, awaiting the conflict.

The butcher's caught the eye with a flare of colour as the light played on the pink and white flesh of sheep, gutted and skewered like victims for sacrifice; the saffron and red quarters of beef, hanging like the limbs of a dismembered Colossus; and the carcasses of pigs, the unclean beasts of the Jews, pallid as a corpse. The butchers passed in and out, sweating and greasy, hoarsely crying the prices as they cut and hacked the meat. The people crowded about, sniffing the odour of dead flesh, hungry and brutal-carnivora seeking their prey.

From Jonah by Louis Stone, 1911

Katherine Susannah Prichard (1883 - 1969)

Coonardoo was singing. Sitting under dark bushes overhung with curly white blossom, she clicked two small sticks together, singing:

("Kangaroos coming over the range in the twilight, and making a devil dance with their little feet, before they begin to feed.")

It was no more than a twitter in the shadow of dark bushes near the veranda; a twitter with the clicking of small sticks. Coonardoo was not supposed to be there at all. Everybody was asleep in the long house of mud bricks and corrugated iron, and under the brushwood sheds beyond the kala miah. But Coonardoo did not want to sleep.

From Coonardoo by Katherine Susannah Prichard

Roderic Quinn (1867 - 1949)

The night-long clamour of winds grew still;

The forest rested, its foes withdrawn;

On sounding ocean and silent hill

There crept a sense of the coming dawn.

A bird awoke on a leaning limb

And fluttered its plumes a moment's space;

Dark purple lay on the sea's far rim:

The sky grew pale as a dying face.

Then all the trees and the rocks and heights

With wondering faces watched the East;

It seemed an altar hung with lights

And waiting for a vestured priest.

And in that intimate first hour

When land and sea rejoiced as one,

And Nature, like an opening flower,

Gave incense, came the burning sun.

Yet, while the hour of gold went by,

I saw through all its pageantry

The vast indifference of the sky,

The heartless beauty of the sea.

For wet and wan, and cold and sped

Beyond the breakers' reach of pearl,

There lay a strong man drowned and dead,

And in his arms a drowned white girl.

At Dawn by Roderic Quinn

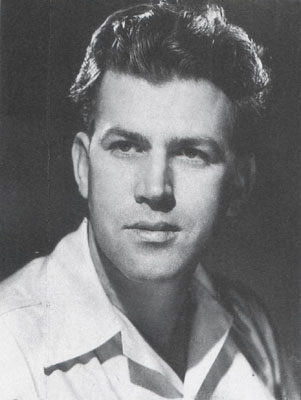

D'Arcy Niland (1919 - 1967)

There was a man who had a cross and his name was Macauley. He put Australia at his feet, he said, in the only way he knew how. His boots spun the dust from its roads and his body waded its streams. The black lines on the map, and the red, he knew them well. He built his fires in a thousand places and slept on the banks of rivers. The grass grew over his tracks, but he knew where they were when he came again.

He had two swags, one of them with legs and a cabbage-tree hat, and that one was the main difference between him and others who take to the road, following the sun for their bread and butter. Some have dogs. Some have horses. Some have women. And they all have mates and companions, or for this reason and that, all of some use. But with Macauley it was this way: he had a child and the only reason he had it was because he was stuck with it.

- From The Shiralee, 1955

Will Ogilvie (1869 - 1963)

Store cattle from Nelanjie! The mob goes feeding past,

With half a mile of sandhill 'twixt the leaders and the last;

The nags that move behind them are the good old Queensland stamp --

Short backs and perfect shoulders that are priceless on a camp;

And these are Men that ride them, broad chested, tanned and tall,

The bravest hearts amongst us and the lightest hands of all:

Oh, let them wade in Wonga grass and taste the Wonga dew,

And let them spread, those thousand head -- for we've been droving too!

Store cattle from Nelanjie! By half-a-hundred towns,

By Northern ranges rough and red, by rolling open downs,

By stock-routes brown and burnt and bare, by flood-wrapped river-bends,

They've hunted them from gate to gate -- the drover has no friends!

But idly they may ride to-day beneath the scorching sun

And let the hungry bullocks try the grass on Wonga run;

No overseer will dog them here to "see the cattle through,"

But they may spread their thousand head -- for we've been droving too!

Store cattle from Nelanjie! They've a naked track to steer;

The stockyards at Wodonga are a long way down from here;

The creeks won't run till God knows when, and half the holes are dry;

The tanks are few and far between and water's dear to buy:

There's plenty at the Brolga bore for all his stock and mine --

We'll pass him with a brave God-speed across the Border line;

And if he goes a five-mile stage and loiters slowly through,

We'll only think the more of him -- for we've been droving too!

Store cattle from Nelanjie! They're mute as milkers now;

But yonder grizzled drover, with the care-lines on his brow,

Could tell of merry musters on the big Nelanjie plains,

With blood upon the chestnut's flanks and foam upon the reins;

Could tell of nights upon the road when those same mild eyed steers

Went ringing round the river bend and through the scrub like spears;

And if his words are rude and rough, we know his words are true,

We know what wild Nelanjies are -- and we've been droving too !

Store cattle from Nelanjie! Around the fire at night

They've watched the pine-tree shadows lift before the dancing light;

They've lain awake to listen when the weird bush-voices speak,

And heard the lilting bells go by along the empty creek;

They've spun the yarns of hut and camp, the tales of play and work,

The wondrous tales that gild the road from Normanton to Bourke;

They've told of fortunes foul and fair, of women false and true,

And well we know the songs they've sung -- for we've been droving too!

Store cattle from Nelanjie! Their breath is on the breeze;

You hear them tread, a thousand head, in blue-grass to the knees;

The lead is on the netting-fence, the wings are spreading wide,

The lame and laggard scarcely move -- so slow the drovers ride!

But let them stay and feed to-day for sake of Auld Lang Syne;

They'll never get a chance like this below the Border Line;

And if they tread our frontage down, what's that to me or you?

What's ours to fare, by God they'll share! for we've been droving too!

From the Gulf by Will Ogilvie

|

Morris West (1916 - 1999)

The Pope was dead. The Camerlengo had announced it. The Master of Ceremonies, the notaries, the doctors had consigned him under signature into eternity. His ring was defaced and his seals were broken. The bells had been rung throughout the city. The pontifical body had been handed to the embalmers so that it might be a seemly object for the veneration of the faithful. Now it lay, between white candles, in the Sistine Chapel with the Noble Guard keeping a death watch under Michelangelo's frescoes of the Last Judgment. The Pope was dead. Tomorrow the clergy of the Basilica would claim him and expose him to the public in the Chapel of the Most Holy Sacrament. On the third day they would bury him, clothed in full pontificals, with a mitre on his head, a purple veil on his face, and a red ermine blanket to warm him in the crypt. The medals he had struck and coinage he had minted would be buried with him to identify him to any who might dig him up a thousand years later. They would seal him in three coffins - one of cypress; one of lead to keep him from the damp and to carry his coat of arms, and the certificate of his death; the last of elm so that he might seem, at least, like other men who go to the grave in a wooden box.

From The Shoes of the Fisherman by Morris West, 1963

|

'P S,' they said.

And 'Vanessa'.

Or sometimes 'Ness'.

PS. PS. PS. PS. Ness. Ness. Ness.

It sounded through his half sleep like surreptitious mice foraging through tissue paper. It was as mysterious as the lateness of the hour - after nine o'clock - and only as far away as the kitchen door, ajar so as to hear him if he should call to them or have a nightmare.

He turned in bed, listening to the whispering undertones, as steady and continuous as a tap left running and broken only by a cough or sometimes a chair scraping back on the linoleum; then a dish being taken from a cupboard and now and then a voice would catch on fire and break adrift from the murmurings, but always with the same word, Vanessa, said sharply like hitting a brass gong at dead of night and then someone would say, 'Shhh, was that him? Did he call out?' and tiptoeing would startle the old floorboards while a shadow grew larger and larger on his wall; bent to hear if he was stirring and so, annoyed with their secrets, he would feign sleep until whoever it was retreated to the kitchen and the whispering hissed up again like damp green eucalyptus logs burning.

From Careful, He Might Hear You by Sumner Locke Elliott, 1963

|

Before you fairly start this story I should like to give you just a word of warning. If you imagine you are going to read of model children, with perhaps a naughtily inclined one to point a moral, you had better lay down the book immediately and betake youself to Sandford and Merton, or similar standard juvenile works. Not one of the seven is really good, for the very excellent reason that Australian children never are. In England, and America, and Africa, and Asia, the little folks may be paragons of virtue -- I know little about them. But in Australia a model child is -- I say it not without thankfulness -- an unknown quantity. It may be that the miasmas of naughtiness develop best in the sunny brilliance of our atmosphere. It may be that the land and the people are young-hearted together, and the children's spirits not crushed and saddened by the shadow of long years' sorrowful hsitory. There is a lurking sparkle of joyousness and rebellion and mischief in nature here, and therefore in children.

From Seven Little Australians by Ethel Turner, 1894

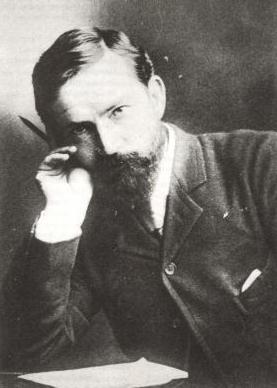

Marcus Clarke (1846 - 1881)

On the evening of 3rd May, 1827, the garden of a large red-brick bow-windowed mansion called North-End House, which, enclosed in spacious grounds, stands on the eastern height of Hampstead Heath, between Finchley Road and the Chestnut Avenue, was the scene of a domestic tragedy.

Three persons were the actors in it. One was an old man, whose white hair and wrinkled face gave token that he was at least sixty years of age. He stood erect with his back to the wall which separates the garden from the Heath, in the attitude of one surprised into sudden passion, and held uplifted the heavy ebony cane, upon which he was ordinarily accustomed to lean. He was confronted by a man of two-and-twenty, unusually tall and athletic of figure, dressed in rough seafaring clothes, and who held in his arms, protecting her, a lady of middle age. The face of the young man wore an expression of horror-stricken astonishment, and the slight frame of the grey-haired woman was convulsed with sobs.

These three people were Sir Richard Devine, his wife, and his only son Richard, who had returned from abroad that morning.

From For the Term of His Natural Life by Marcus Clarke, 1874

|

One bleak afternoon in the winter of 1893 a young man stood in the doorway of a shop in Jackson Street, Carringbush, a suburb of the city of Melbourne, in the Colony of Victoria. The shop was single-fronted and above its narrow door was the sign CUMMIN'S TEA SHOP. In its small window stood a tea-chest with a price ticket leaning against it. The man was of short, solid build and was neatly dressed in a dark-grey suit. His face was clean-shaven. He wore a celluloid collar and a dark tie. With his left hand he was spinning a coin. It was a shiny golden coin, a sovereign.

Standing on the footpath facing him from a few feet away was a tall policeman in uniform, whose small, unintelligent eyes followed the flight of the coin as it spun up a few feet and fell into the palm of the young man's hand, only to spin rhythmically upwards again and again. The policeman said: "This shop is on my beat. I have had complaints that you are conducting an illegal totalisator here."

A cold wind blew through the door fanning against the young man's trouser legs, revealing that he was extremely bow-legged. From a distance, the first noticeable characteristic was his bandiness, but, at close range, his eyes were the striking feature. They were unfathomable, as if cast in metal; steely grey and rather too close together; deepset yet sharp and penetrating. The pear-shaped head and the large-lobbed ears, set too low and too far back, gave him an aggressive look, which was heightened by a round chin and a lick of hair combed back from his high sloping forehead like the crest of a bird. His nose was sharp and straight; under it a thin, hard line was etched for a mouth. He was twenty-four years of age, and his name was John West.

From Power Without Glory by Frank Hardy, 1950

|

Henry Handel Richardson (1870 - 1946)

(Ethel Florence Lindesay Richardson)

In a shaft on the Gravel Pits, a man had been buried alive. At work in a deep wet hole, he had recklessly omitted to slab the walls of a drive; uprights and tailors yielded under the lateral pressure, and the rotten earth collapsed, bringing down the roof in its train. The digger fell forward on his face, his ribs jammed across his pick, his arms pinned to his sides, nose and mouth pressed into the sticky mud as into a mask; and over his defenceless body, with a roar that burst his ear-drums, broke stupendous masses of earth.

His mates at the windlass went staggering back from the belch of violently discharged air: it tore the wind-sail to strips, sent stones and gravel flying, loosened planks and props. Their shouts drawing no response, the younger and nimbler of the two - he was a mere boy, for all his amazing growth of beard - put his foot in the bucket and went down on the rope, kicking off the sides of the shaft with his free foot. A group of diggers, gathering round the pit-head, waited for the tug at the rope. It was quick in coming; and the lad was hauled to the surface. No hope: both drives had fallen in; the bottom of the shaft was blocked. The crowd melted with a "Poor Bill - God rest his soul!" or with a silent shrug. Such accidents were not infrequent; each man might thank his stars it was not he who lay cooling down below. And so, since no more washdirt would be raised from this hole, the party that worked it made off for the nearest grog-shop, to wet their throats to the memory of the dead, and to discuss future plans.

From Australia Felix by Henry Handel Richardson, 1917

|

John Shaw Neilson (1872 - 1942)

The young girl stood beside me. I

Saw not what her young eyes could see:

- A light, she said, not of the sky

Lives somewhere in the Orange Tree.

- Is it, I said, of east or west?

The heartbeat of a luminous boy

Who with his faltering flute confessed

Only the edges of his joy?

Was he, I said, borne to the blue

In a mad escapade of Spring

Ere he could make a fond adieu

To his love in the blossoming?

- Listen! the young girl said. There calls

No voice, no music beats on me;

But it is almost sound: it falls

This evening on the Orange Tree.

- Does he, I said, so fear the Spring

Ere the white sap too far can climb?

See in the full gold evening

All happenings of the olden time?

Is he so goaded by the green?

Does the compulsion of the dew

Make him unknowable but keen

Asking with beauty of the blue?

- Listen! the young girl said. For all

Your hapless talk you fail to see

There is a light, a step, a call

This evening on the Orange Tree.

- Is it, I said, a waste of love

Imperishably old in pain,

Moving as an affrighted dove

Under the sunlight or the rain?

Is it a fluttering heart that gave

Too willingly and was reviled?

Is it the stammering at a grave,

The last word of a little child?

- Silence! the young girl said. Oh, why,

Why will you talk to weary me?

Plague me no longer now, for I

Am listening like the Orange Tree.

The Orange Tree by John Shaw Neilson, 1919

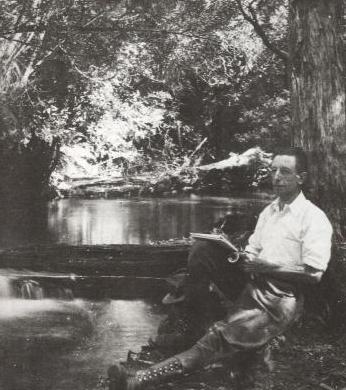

Joseph Furphy (1843 - 1912)

Unemployed at last!

Scientifically, such a contingency can never have befallen of itself. According to one theory of the Universe, the momentum of Original Impress has been tending toward this far-off, divine event ever since a scrap of fire-mist flew from the solar centre to form our planet. Not this event alone, of course; but every occurrence, past and present, from the fall of captured Troy to the fall of a captured insect. According to another theory, I hold an independent diploma as one of the architects of our Social System, with a commission to use my own judgment, and take my own risks, like any other unit of humanity. This theory, unlike the first, entails frequent hitches and cross-purposes; and to some malign operation of these I should owe my present holiday.

Orthodoxly, we are reduced to one assumption: namely, that my indomitable old Adversary has suddenly called to mind Dr. Watts's friendly hint respecting the easy enlistment of idle hands. Good. If either of the first two hypotheses be correct, my enforced furlough tacitly conveys the responsibility of extending a ray of information, however narrow and feeble, across the path of such fellow-pilgrims as have led lives more sedentary than my own -- particularly as I have enough money to frank myself in a frugal way for some weeks, as well as to purchase the few requisites of authorship.

From Such is Life by Tom Collins (Joseph Furphy), 1903

Judith Wright (1915 - 2000)

Beside his heavy-shouldered team,

thirsty with drought and chilled with rain,

he weathered all the striding years

till they ran widdershins in his brain:

Till the long solitary tracks

etched deeper with each lurching load

were populous before his eyes,

and fiends and angels used his road.

All the straining journey grew

a mad apocalyptic dream,

and he old Moses, and the slaves

his suffering and stubborn team.

Then in his evening camp beneath

the half-light pillars of the trees

he filled the steepled cone of night

with shouted prayers and prophecies.

While past the campfire's crimson ring

the star-struck darkness cupped him round,

and centuries of cattlebells

rang with their sweet uneasy sound.

Grass is across the waggon-tracks,

and plough strikes bone across the grass,

and vineyards cover all the slopes

where the dead teams were used to pass.

O vine, grow close upon that bone

and hold it with your rooted hand.

The prophet Moses feeds the grape,

and fruitful is the Promised Land.

Bullocky by Judith Wright, 1944

George Turner (1916 - 1997)

Walk a crowded street, see a hundred people in a minute. They are there, accepted, signifying nothing. Yet -- A stick swells with flesh, puts forth soul. At a subliminal warning eyes and brain communicate; you look at the face. It passes, anonymous as the wind, but a ripple has marked the mind. It could have been Joe who passed. You did not catch a breath or stare in his wake, but noticed him in a flicker of consciousness which did not quite emerge as, That one was different from the rest -- for an instant a person. He is not a big man, being slender and small-boned, but heavier and stronger than the casual glance might gather. There might have been a touch of the cat in him. Or the tiger ... even in stillness he suggested movement.

From A Waste of Shame by George Turner, 1965

|

Charles Harpur (1813 - 1868)

Not a bird disturbs the air!

There is quiet everywhere;

Over plains and over woods

What a mighty stillness broods.

Even the grasshoppers keep

Where the coolest shadows sleep;

Even the busy ants are found

Resting in their pebbled mound;

Even the locust clingeth now

In silence to the barky bough:

And over hills and over plains

Quiet, vast and slumbrous, reigns.

Only there's a drowsy humming

From yon warm lagoon slow coming:

'Tis the dragon-hornet - see!

All bedaubed resplendently

With yellow on a tawny ground -

Each rich spot nor square nor round,

But rudely heart-shaped, as it were

The blurred and hasty impress there,

Of vermeil-crusted seal

Dusted o'er with golden meal:

Only there's a droning where

Yon bright beetle gleams the air -

Gleams it in its droning flight

With a slanting track of light,

Till rising in the sunshine higher,

Its shards flame out like gems on fire.

Every other thing is still,

Save the ever wakeful rill,

Whose cool murmur only throws

A cooler comfort round Repose;

Or some ripple in the sea

Of leafy boughs, where, lazily,

Tired Summer, in her forest bower

Turning with the noontide hour,

Heaves a slumbrous breath, ere she

Once more slumbers peacefully.

O 'tis easeful here to lie

Hidden from Noon's scorching eye,

In this grassy cool recess

Musing thus of Quietness.

Dymphna Cusack (1902 - 1981)

Angus McFarland stepped out of the private hire car at the main entrance of the Hotel South Pacific and snapped a brusque reply to the commissionaire's "Good evening, sir." The chauffeur pocketed his tip, touched his cap, and the car moved smoothly down Macquarie Street.

Angus was hot and uncomfortable. The unseasonable heat of the spring afternoon beat up from the pavement, and across the street the glare from the setting sun blazed back from the fan-shaped transoms of Parliament House. He noticed with rising irritation that the sky was angry with clouded fire, and flaming mares' tales rioted in the upper air. That would mean another hot day tomorrow - probably a westerly, judging by the sky.

What a fool he had been to let his sister persuade him to go to Wahroonga on a day like this, even if Ian and his family were down from the country on one of their infrequent visits. It had been damned boring as well as uncomfortable -- nothing but family business and gossip. Serve him right for going; he had nothing whatever in common with Virginia or Ian, and he ought to have known better. He should have spent the afternoon up at the Continental Gymnasium having his usual Friday Turkish bath and massage to get himself in form for his evening with Deborah. A man wanted to feel at his best with a girl as vibrant and beautiful as she was -- particularly when he was seventeen years older.

From Come in Spinner by Dymphna Cusack and Florence James

John O'Brien (1878 - 1952)

"We'll all be rooned," said Hanrahan,

In accents most forlorn,

Outside the church, ere Mass began,

One frosty Sunday morn.

The congregation stood about,

Coat-collars to the ears,

And talked of stock, and crops, and drought,

As it had done for years.

"It's looking crook," said Daniel Croke;

"Bedad, it's cruke, me lad,

For never since the banks went broke

Has seasons been so bad."

"It's dry, all right," said young O'Neil,

With which astute remark

He squatted down upon his heel

And chewed a piece of bark.

And so around the chorus ran

"It's keepin' dry, no doubt."

"We'll all be rooned," said Hanrahan,

"Before the year is out."

From Said Hanrahan by John O'Brien

Barcroft Boake (1866 - 1892)

That's where the dead men lie!

There where the heat-waves dance forever -

That's where the dead men lie!

That's where the Earth's loved sons are keeping

Endless tryst: not the west wind sweeping

Feverish pinions can wake their sleeping -

Out where the dead men lie!

Where brown Summer and Death have mated -

That's where the dead men lie!

Loving with fiery lust unsated -

That's where the dead men lie!

Out where the grinning skulls bleach whitely

Under the saltbush sparkling brightly;

Out where the wild dogs chorus nightly -

That's where the dead men lie!

From Where the Dead Men Lie by Barcroft Boake

|

Gwen Harwood (1920 - 1995)

Show me the order of the world,

the hard-edge light of this-is-so

prior to all experience and common

to both world and thought, no model,

but the truth itself.

Language is not a perfect game,

and if it were, how could we play?

The world's more than the sum of things

like moon, sky, centre, body, bed,

as all the singing masters know.

Picture two lovers side by side

who sleep and dream and wake to hold

the real and imagined world

body by body, word by word

in the wild halo of their thought.

"Thought is Surrounded by a Halo" [Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations 97] by Gwen Harwood

Dal Stivens (1911 - 1997)

I am the author and amateur naturalist mentioned in the first chapter of this rather unorthodox autobiography by Harold Craddock. I had known and respected Harold Craddock for some years - his contributions to Australian ornithology have been outstanding - but I was never a close friend. Accordingly, I was a little surprised when he asked me to act as his literary godfather, as it were, and handed me the manuscript which with only slight editing appears on the pages that follow. His original idea was that I should use his autobiography as part of the source material for an account of the expedition he led to central Australia in 1967. His manuscript, as he was at pains to point out, was a subjective account and was deficient in many details. "Moreover, it's a bit wild in places - you'll need to get people to corroborate some of the things I've written," he said. This was my own first reaction, and I, accordingly, spent several months interviewing other people who had accompanied Harold Craddock and gathering the mass of material necessary for a straightforward account of the Craddock and Drake Expedition to find the rare night parrot. It was only when I had accumulated a mass of material that I realized that the finest memorial to my friend was to publish his autobiography much as he had written it, with only minor interpolations by others where accounts differed. Who was I, for instance, to judge whether Harold Craddock, or someone else, was being truthful? The truth about anything must be disputable. As he asks in the autobiography, which is the reality and which is the dream? Most of the people mentioned have consented to the references made to them even though they did not always agree that they acted as Harold Craddock said they did or from the motives he imputed to them. They have, in fact, behaved with extraordinary magnanimity. In a few places only they have interpolated mild demurrers. Occasionally it has been necessary to use invented names and alter details.

From A Horse of Air by Dal Stivens.

Henry Kendall (1839 - 1882)

By channels of coolness the echoes are calling,

And down the dim gorges I hear the creek falling:

It lives in the mountain where moss and the sedges

Touch with their beauty the banks and the ledges.

Through breaks of the cedar and sycamore bowers

Struggles the light that is love to the flowers;

And, softer than slumber, and sweeter than singing,

The notes of the bell-birds are running and ringing.

The silver-voiced bell birds, the darlings of daytime!

They sing in September their songs of the May-time;

When shadows wax strong, and the thunder bolts hurtle,

They hide with their fear in the leaves of the myrtle;

When rain and the sunbeams shine mingled together,

They start up like fairies that follow fair weather;

And straightway the hues of their feathers unfolden

Are the green and the purple, the blue and the golden.

From Bell-Birds by Henry Kendall

Thea Astley (1925 - 2004)

'I've never sailed the Amazon. I've never reached Brazil,' she quoted, and I've never been to a literary festival or a poetry reading, she thought, and listened to poets read, awed by their own genius.

A lot of things she hadn't done. Sitting now, useless maybe, in her upstairs flat with a view of the town's pub, grocery store, unused picture show, council building and primary school skulking by the wattles near where the creek used to flow. But I might write a book -- something -- she decided, having the wherewithal: table, typewriter, a new ream of paper, and angry ideas. And alone-time in the hot evenings. Past fifty, she admitted. And had really done nothing except move from one day to the next, accepting the vagaries of personal weather. These were written on her anxious face, blinked behind her glasses; they turned up the corners of her mouth that tried to conceal its amusement in a town that went for the most explicit of laughs. All she had to do was insert a page in the typer, adjust her kitchen chair, flex her fingers as if she were about to crash into the Rach II and begin.

From Drylands by Thea Astley

Xavier Herbert (1901 - 1984)

Although that northern part of the Continent of Australia which is called Capricornia was pioneered long after the southern parts, its unofficial early history was even more bloody than that of the others. One probable reason for this is that the pioneers had already had experience of subduing Aborigines in the South and hence were impatient of wasting time with people who they knew were determined to take no immigrants. Another reason is that the Aborigines were there more numerous than in the South and more hostile because used to resisting casual invaders from the near East Indies. A third reason is that the pioneers had difficulty in establishing permanent settlements, having serveral times to abandon ground they had won with slaughter and go slaughtering again to secure more. This abandoning of ground was due not to the hostility of the natives, hostile enough though they were, but to the violence of the climate, which was not to be withstood even by men so well equipped with lethal weapons and belief in the decency of their purpose as Anglo-Saxon builders of Empire.

From Capricornia by Xavier Herbert

C.J. Dennis (1876 - 1938)

'Er name's Doreen ...Well, spare me bloomin' days!

You could er knocked me down wiv 'arf a brick!

Yes, me, that kids meself I know their ways,

An' 'as a name for smoogin' in our click!

I just lines up 'an tips the saucy wink.

But strike! The way she piled on dawg! Yer'd think

A bloke was givin' back-chat to the Queen....

'Er name's Doreen.

"The Intro" from The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke by C.J. Dennis

Amy Witting (1918 - 2001)

A week before Isobel Callaghan's ninth birthday, her mother said, in a tone of mild regret, 'No birthday presents this year! We have to be very careful about money this year.'

Every year at this time she said this; every year Isobel chose not to believe it. Her mother was just saying that, she told herself, to make the present more of a surprise. Experience told her that there would be no present. As soon as they stepped out of the ferry onto the creaking wharf and set out for Mrs Terry's lakeside boarding house, where they spent the summer holidays, the flat reedy shore, the great Moreton Bay fig whose branches scaffolded the air of the boarding-house garden, the weed-bearded tennis court and the cane chairs with their faded flabby cushions, all spoke to Isobel of desolate past birthdays, but she did not believe experience, either. Day by day she watched for a mysterious shopping trip across the lake, for in the village there was only one tiny store which served as a post office too; when no mysterious journey took place, she told herself they must have brought the present secretly from home. Even on the presentless morning she would not give up hope entirely, but would search in drawers, behind doors, under beds, as if birthday presents were supposed to be hidden, like Easter eggs in the grass.

From I For Isobel by Amy Witting

Christopher Brennan (1870 - 1932)

How old is my heart, how old, how old is my heart,

and did I ever go forth with song when the morn was new?

I seem to have trod on many ways: I seem to have left

I know not how many homes; and to leave each

was still to leave a portion of mine own heart,

of my old heart whose life I had spent to make that home

and all I had was regret, and a memory.

So I sit and muse in this wayside habour and wait

till I hear the gathering cry of the ancient winds and again

I must up and out and leave the embers of the hearth

to crumble silently into white ash and dust,

and see the road stretch bare and pale before me: again

my garment and my house shall be the enveloping winds

and my heart be fill'd wholly with their old pitiless cry.

How Old is My Heart, How Old, How Old is My Heart by Christopher Brennan

Kenneth Slessor (1901 - 1971)

After the whey-faced anonymity

Of river-gums and scribbly-gums and bush,

After the rubbing and the hit of brush,

You come to the South Country

As if the argument of trees were done,

The doubts and quarrelling, the plots and pains,

All ended by these clear and gliding planes

Like an abrupt solution.

From South Country by Kenneth Slessor

Mary Gilmore (1865 - 1962)

I'm old Botany Bay;

Stiff in the joints,

Little to say.

I am he

Who paved the way,

That you might walk

At your ease to-day;

I was the conscript

Sent to hell

To make in the desert

The living well;

I bore the heat,

I blazed the track --

Furrowed and bloody

Upon my back.

From Old Botany Bay by Mary Gilmore

Victor Daley (1858 - 1905)

Stand up, my young Australian,

In the brave light of the sun,

And hear how Freedom's battle

Was in the old days lost - and won.

The blood burns in my veins, boy,

As it did in years of yore,

Remembering Eureka,

And the men of 'Fifty-four..

From "Eureka" by Victor Daley

A.B. ("Banjo") Paterson (1864 - 1941)

I had written him a letter which I had, for want of better

Knowledge, sent to where I met him down the Lachlan, years ago,

He was shearing when I knew him, so I sent the letter to him,

Just "on spec", addressed as follows: "Clancy, of The Overflow".

And an answer came directed in a writing unexpected,

(And I think the same was written in a thumbnail dipped in tar)

'Twas his shearing mate who wrote it, and verbatim I will quote it:

"Clancy's gone to Queensland droving, and we don't know where he are."

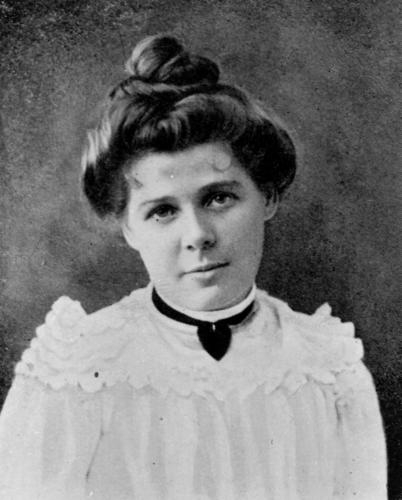

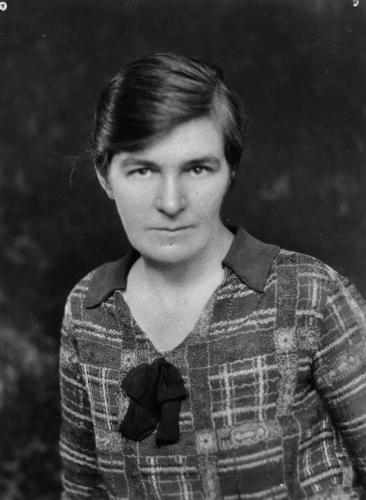

Miles Franklin (1879 - 1954)

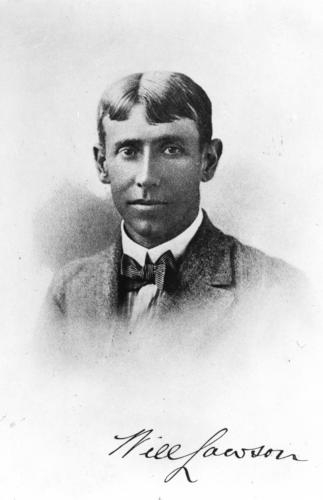

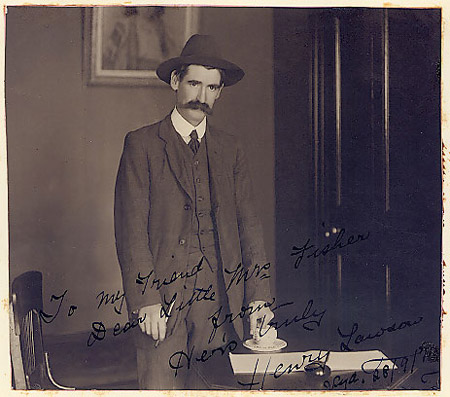

Henry Lawson (1867 - 1922)

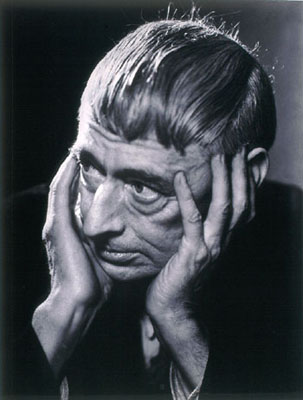

Patrick White (1912 - 1990)

Christina Stead (1902 - 1983)