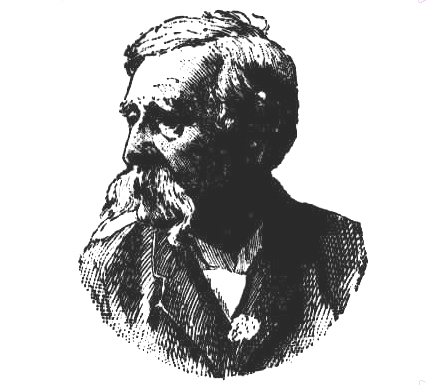

Prominent amongst the early band of bush balladists developed by the Sydney "Bulletin" and yet with a distinctive note of his own is Edward Dyson. A. B. Paterson, Henry Lawson, John Farrell, and Edward Dyson, it has been said, all graduated in the same school, that of journalism and the Sydney "Bulletin" was their nursing mother. John Farrell is the oldest member of this little group, Edward Dyson is the youngest. Like Lawson, Dyson has written wore notable work in prose than in verse, but his poems constitute a unique contribution to the literature of Australia.

''There is a certain similarity of style running through the whole four," says Henry G. Turner, of this group, in "The Development of Australian Literature," and though they frequently view the same subject from a totally opposite standpoint, the influence of Adam Lindsay Gordon, of Bret Harte, and of Brunton Stephens is in them all." Apart from their common interest in singing in differing strains of the life of the bush, Dyson is distinguished from the other members of this group in the peculiar inspiration he drew from the mines and the miners in the days when it was possible to invest mines and mining fields with a poetical glamour. Dyson is also distinguished by a genial humour, which in his prose run to the broadest farce.

In an account he once wrote of his methods of work, Edward Dyson asserted that he went though "a process of soakage and seepage." He said that he allowed his experiences to soak for years in his memory before he attempted to draw upon them for use in fashioning stories and verses, as he held that experience needed the mellowing influence of time before it acquired literary value. His variegated literary output must therefore be regarded as the evidence of a rich and varied experience which has "soaked and seeped," in his own geological metaphor, through the personality of the writer.

Edward Dyson was born at Morrison's, near Ballarat, in 1865. His family had come to Australia in 1852 and were in the thick of all the gold rushes of the period. Shortly after Edward's birth the family moved to the big mining field of Alfredton. Later moves carried the family to Melbourne, Bendigo, and Ballarat until, when Edward was 11 years old, they were back at Alfredton again. In the meantime the big mines had closed down and the worked-out shafts and abandoned workings excercised a peculiar fascination for the young Dyson, to be reflected in such of his later work as "The Worked-out Mine," with its--

"Above the shaft in measured space

A rotted rope swings to and fro,

Whilst o'er the plat and on the brace

The silent shadows come and go.

And there below, in chambers dread,

Where darkness like a fungus clings,

Are lingering still the old mine's dead,

Bend o'er and hear their wisperings."

Other experiences of this period when Dyson actively shared the adventures of the youngsters of his age, are no doubt reflected in the rollicking boys' story - "The Gold Stealers," in which Waddy forms a counterpart of Alfredton. Before he had reached 13, Dyson had set out to explore the world as assistant to a hawker, his adventures in this capacity providing the raw material for his later story "Tommy the Hawker." Returning to Ballarat, he worked for a while as whim boy, his recollections of this life providing the foundations for his most effective poem, "The Old Whim Horse," paralleled by Dyson's own dream, as he sang:--

"See the old horse take, like a creature dreaming,

On the ring once more his accustomed place;

But the moonbeams full on the ruins streaming

Show the scattered timbers and grass-grown brace;

Yet he hears the sled in the smithy falling,

And the empty truck as it rattles back,

And the boy who stands by the anvil, calling;

And he turns and backs, and 'takes up slack.'"

Later mining at Clunes and Bungaree, on the alluvial field at Lefroy in Tasmania, and then back as a trucker in a deep mine, and afterwards at battery building in Victoria, Dyson became familiar with every detail of the mining life of the period. This experience is all reflected in his first book of poems ''Rhymes from the Mines and other Lines," published in 1896. In "The Trucker," in particular is a vivid account of the life of the lads which Dyson had shared:

"Yes, the truckers' toil is rather heavy grafting at a rule --

Much heavier than the wages, well I know:

But the life's not full of trouble and the fellow is a fool

Who cannot find some pleasure down below."

And in "The Prospectors" he paints the characteristics of a type that is by no means extinct to-day:--

"We are common men with the faults of most, and a few that ourselves have grown,

With the good traits, too, of the common herd, and some more that are all our own;

We have drunk like beasts and have fought like brutes, and have stolen and lied and slain.

And have paid the score in the way of men -- in remorse and fear and pain.

We have done great deeds in our direst needs in the horrors of burning drought,

And at mateship's call have been true through all to the death with the Furthest Out."

It has been said that Dyson's poems, on their first appearance, suffered by comparison with those of Paterson and Lawson because his mining songs lacked any distinctive Australian note, but it is certain that the vivid realism, the genial sense of humour and the kindly human understanding which inspires these simple poems will ensure that the best of them will live.

In his prose work Dyson has achieved a number of successes. "Fact'ry 'Ands" and "Benno" were responsible for the creation of characters which have become as well-known as the most famous characters of Dickens. The characterisation is fine throughout, but the humour runs to the broadest farce.

"Below and On Top," and "The Missing Link," contain some of the best of Dyson's short stories. With "In the Roaring Fifties," a more ambitious novel, published in 1906, Dyson was less successful than with his lighter sketches. Many other short stories have not yet appeared in book form.

Altogether Edward Dyson has been responsible for a notable addition to the literature of Australia. He has opened new veins and exploited them according to their peculiar requirements. Lacking the imagination which would have raised his creations to the higher levels of literature, he has shown himself a faithful recorder of much that is interesting and a versatile and adaptable craftsman. Living wholly by his craft he has shown that it is possible even in Australia to devote a life to writing and manage to live.

First published in The Morning Bulletin [Rockhampton], 12 January 1931

[Thanks to the National Library of Australia's newspaper digitisation project for this piece.]