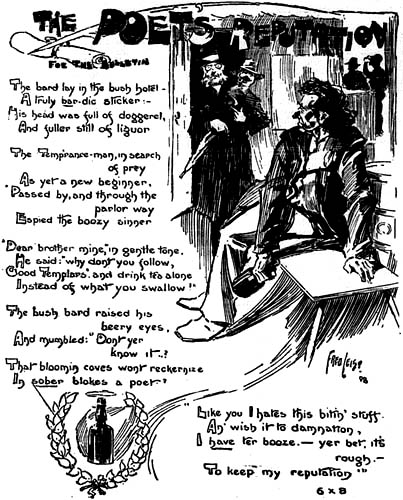

Who was to gather up the two strands of life in Australia -- which I have perforce called the belltoppers and the moleskins -- and make from them something new? Who was to show us as a coherent group instead of fugitive colonials? Such questions are answered by the name of a poet whose great work has been to put revealing questions. Through all his books Bernard O'Dowd makes demands and challenges. His first book, with its austere, democratic chants in the barest of ballad stanzas, was called not "Downward," as printers so often have it, but "Dawnward?" the query being not only in the title, but wistfully pervasive:

Flames new disaster for the race

Or can it be the Dawn?

His earliest and most famous sonnet, "Australia," which has been strangely described as aggressively patriotic, deserves rather to be called an ode written in time of doubt:

Last Sea-Thing dredge by Sailor Time from space,

Art thou a drift Sargasso, where the west

In halcyon calm rebuilds her fatal nest,

Or Delos of a coming Sun-God's race?

Not much positive swashbuckling there. Indeed, throughout his questioning poems that have appeared over several decades, O'Dowd is hardly more confident about this Terra Australis Incognita than was Robert Burton, three centuries before him. Burton, too, suggests both sides: "Antipodes (which they made it a doubt whether Christ died for)"; and "whether that hungry Spaniard's discovery of the Unknown South Land be as true as his of Utopia .... it cannot choose but yield in time some flourishing kingdoms to future ages." For the matter of our being antipodes -- "the underworld," as the Oxford Dictionary condenses it -- O'Dowd uses a gesture of some warmth. Aware, as a child or a scientist is, that a ball has no up or down, he laughs, with a moment's swagger, at the traditional north, the top of the map, from which all blessings must for ever drop down. Cannot the south, perhaps, prove a source of renewal?

Antipodeon? Whew! We are the top,

The fountain . . . .

So begins the sextet of a brilliant sonnet in the fourth of his books, "The Seven Deadly Sins." But it is in the fifth book, "The Bush," with its single, long poem in a striking ten-line stanza of his own, that O'Dowd has put his questions about Australia at full length; solemnly, whimsically, now by allusion, now by sensitive and powerful descriptive passages; again and again with the movement of high poetry, so that, as cannot be shown here in this crumble of prosy comment, the ideas are "carried alive into the heart by passion."

A Significant Link

This questioner-poet brought to his ever-growing task a hoard of curious learning and an almost tactile sensitiveness to a landscape that had hardly begun to be frankly seen and recorded in words. In possessing these two gifts, one recondite, the other intimate, he recalls, not for the first time, the Irish poet A.E., whose twin passions for agriculture and for Hindoo religions have been hit off by James Joyce in a satirical dramatic passage of "Ulysses." Joyce pictures A.E. as a fantastic mythical figure exclaiming "Patsypunjaub!" and so expressing the two sides of his being. O'Dowd, firmly based in the realities of the land that bred him, yet having his head in "The Silent Land," with its overtones, linked the academic writers and the bush bards. Drawing down upon Australia in "The Bush" all the Utopian prophecies,

Bacon foretold her, Campanella, More,

He is aware, too, of our yearly spectacle, north to south,

..... the Wattle River, rolling,

Exuberant and golden towards the sea;

O'Dowd weaves past and present into patterns that are continually repeated, yet never the same. He has shaped his urgent questions over and over, never content with a single answer. Is this unknown south land, indeed, to give flourishing kingdoms to succeeding ages? Then what is a flourishing kingdom? Is it perhaps like this?

There, lazy fingers of a breeze have scattered

The distant blur of factory chimney smoke

In poignant groups of all the young lives shattered

To feed the ravin of a piston-stroke!

What is a flourishing kingdom to be?

No corsair's gathering ground, no tryst for schemers

No chapman Carthage to a huckster Tyre,

She is the Eldorado of old dreamers,

The Sleeping Beauty of the world's desire!

But here arises a question of another sort. Beauty? In his curious and brilliant preface to Gordon's poems, Marcus Clarke wrote, "In Australia alone is to be found the grotesque, the weird, the strange scribblings of Nature learning how to write" -- no other beauty. Was Barron Field's horrible old verse wrong in granting that this fifth part of the earth was redeemed, from that utter failure with which he had forced it to rhyme? And was Aldous Huxley right in his instructive use of an Australian phenomenon for a mere gruesome measurement of time?

The time of waiting began. Each second the earth travelled 25 miles and the prickly pear

covered another five rods of Australian ground.

Macabre, grotesque, unlovely to alien eyes;- that was Australia. O'Dowd accepts Clarke's challenge, recognises the degree of honesty in his vision, shares it and transcends it. Without reluctance, he upholds the tragic quality in the land- scape that has confronted him since his birth:

Out of the heights what influence is pouring

Thin desolation on your haunted face?

Again he dreads that alien forces should seek

To drown the chord or purifying sorrow

Born ere the world, that pulses through your trees.

Born ere the world. With such a statement O'Dowd meets the more serious and persistent charge that is made against a new country, especially against the newest of all -- the simple charge of being new. Chesterton and Belloc, for instance, in book after book, have casually mentioned an "a priori" detestation of us as crude, empty, dull. At best we are to such onlookers a bad joke; but no, they would never subject themselves to the pangs of looking on. At most, they may now glance at America, which certainly started off before us; and what do they see there?

Perhaps Herny James could still tell them, with another of his comprehensive sighs. (And for America let us read, again, "Australia.")

There is in America no State in the European sense of the word, No sovereign, no court, no

personal loyalty, no aristocracy, no church, no clergy, no army, no diplomatic service, no

county gentleman, no palaces, no castles, nor manors, nor old country houses, nor

parsonages, nor thatched cottages, nor ivied ruins; no cathedrals, not abbeys, nor little

Norman churches; no great universities, nor public schools; no literature, no novels, no

museums, no pictures, ...

This was written perhaps 50 years ago, but we are still much newer than America was then. The charge is valid: a new country has none of the mellow gifts of age. How, then, can it live?

A Whimsical Discussion

It is a poet who answers, moving on a plane where Time is not the mere calen- dar. "For Troy hath ever been," and the great themes of human love and strife reappear

Across each terraced aeon Time hath sowed

With green tautology of vanished years.

That tautology, that strange inevitable repetition, can save us. "The towers that Phoebus builds can never fall." But here, in the poem, the argument rather shifts, and the verse from being a poetic utterance becomes a discussion, whimsical and bizarre. To one who looks back from that great day when we shall all be contemporaries together, this newest continent, says the poet, will seem no younger than Babylon. Readers of the future will readily confuse Euripides with the Australian, Gilbert Murray, his translator; they will confuse "Elzevir," the Australian critic, with Longinus who counselled Zenobia.... The verses become full of names, sometimes wittily handled; but it was :Elzevir" himself who protested, when "The Bush" first appeared, that he was like a fly in amber -- but in the cloudier part of superb amber, he might have added. For those wayward and cloudy stanzas in this poem are outnumbered by others of a golden clarity; and in many passages O'Dowd's almost legal statements of both sides, both possibilities, have given a profundity that this poet could achieve in no other way.

The questioning poet, O'Dowd has been accustomed to remember the phrase of one who guided his youth, Walt Whitman. 'The poet is the Answerer." The man of law, O'Dowd, may well have remembered that it is only by the zig-zag of questions that you arrive at a verdict. He leads toward our answer.

First published in The Argus, 23 February 1935

[Thanks to the National Library of Australia's newspaper digitisation project for this piece.]