(Died March 18, 1935)

She has put aside her lyre a little while

She, the sweet singer, vendor of gay song;

She has put down her lyre, and with a smile

Drifted to other fields, but not for long.

But not for long. Someday, where now she lingers

She will grow weary, and will swiftly burn

To feel the strings again beneath her fingers,

Then, like, a wandering minstrel, will return.

She will return, with nuance and with laughter,

Old echoes waking in the street and hill,

And all our kin and those who follow after

Will know her note, and call her singer still!

First published in The Courier-Mail, 23 March 1935

October 2011 Archives

In the "Arabian Nights" we read of one Serendib, an Oriental merchant who went about the bazaars of Bagdad picking up all sorts of odds and ends, and making out of them, with deft artistry, things new and strange. Horace Walpole was a confessed disciple of Serendib, and decorated his bijou Gothic castle at Twickenham with lovely bits of statuary and cabinets crammed with coins and porcelain, and a hundred quaint ornaments in brass. Mrs. Mabel Forrest, our Queensland poetess, is another follower of Serendib, and from her magic pack of fancies she has for the last score of years or more been bringing forth, like a persuasive pedlar, a remarkable series of opalescent poems redolent of cedar and cinnamon, and reminiscent of the tinkle of temple bells. One wonders how she does it, as one wonders at a conjurer. Perhaps her fellow Australians have fallen into the placid mood of acceptance -- imagining that the things of beauty she has been producing with such fresh lustre and apparent ease are the things one expects as a matter of course from a conjurer. Long ago Kendall, thinking of Harpur, chided his countrymen on "the life austere that waits upon the man of letters here," and it would be a thousand pities if a similar indifference were to chill the heart of such a music-maker and dreamer of dreams as Mrs. Mabel Forrest has been.

Upon an iron balcony above the city street,All day the pale, sick woman lies; across her idle feet

A striped rug from Arabia; and in her slender hands

The magic book that tells her tales of undiscovered lands.

The day will come when her magic book, like Prospero's, shall sink "deeper than did ever plummet sound," but, at least, let us reassure her that we love her sweet fantasies and re-echo in our hearts the clairvoyant sympathy which she has shown in many a poem for the weary and the heavy-laden. To do this is simple gratitude for the place she has taken since the death of Brunton Stephens as our representive Queensland poet, the one who has turned into shapes of beauty our common experiences of sunset and moonrise, of busy streets and shaded garden crofts, of child- hood's dreams and the wistful reveries of age.

Mrs. Mabel Forrest is a romantic lyricist. She is not a balladist like Banjo Paterson or Harry Lawson, for though she knows her Bush as intimately as any teller of its epical tales, her strength lies in the evocation of her thronging fancies, in the embroidery of them with the colours of masque or pageant, and in the lilting progress she gives to them the sound of shawms and cymbals. It is her most frequent method to take hold of some simple, common thing like a worn door-mat and turn it into a dream barge on which she visits the ports and happy havens of romance.

Worn here and there by little feet,The mat upon the floor is string;

And when you shake it, full of dust:

By day an ordinary thing.

But you should see it when at night

The house is still and stars are bright.

The poem becomes an incantation, summoning up from the vasty deep "the cloud capp'd towers, the gorgeous palaces, the solemn temples, the great globe itself," as by the waving of a magic wand. Image swiftly follows image, aglow with colour and aromatic with incense, till the exquisite and passionate sensuousness of it all exercises on the mind of the listener an almost hypnotic charm, as if we were indeed looking from magic casements on the foam of perilous seas in fairy lands forlorn. Mrs. Forrest's imagination is akin to that of Keats, who could not see a sparrow on the garden path without feeling that he was that very bird hopping about on the gravel. She visualises all objects within her ken, and her effects are so vivid that they do not need the underlining she sometimes gives to them. It is because of this art of make-believe that many of her poems fascinate the minds of imaginative children. She shares this knack with Robert Louis Stevenson, in his "Child's Garden of Verses." Here for example is one verse from "Goblin Time":

In goblin time the iron tank --A harmless creature in its way --

Grows like some awful giant's head

That crouched behind our house all day.

The clothes-line hanging in the yard,

With fluttering humble things upon,

Has changed into a gallows tree,

That holds a dangling skeleton.

Mrs. Forrest's imagination is populous with elfin folk. Another feature of her poetry is her riotous delight in decoration. She hangs festoons of flowers upon her rhymes, and threads them with necklaces of jewellery -- pearls, rubies, diamonds, turquoises, silver and gold. She clothes her figures with old time costumes or the silks of to-day. And as for colour, surely no poet has ever excelled her there. "Red Broom Handles " prompt her imagination to play with all shades of red from the caps of the pixies and ochre fishing-boats to the red of Revolution itself. The "Queen's Room" is a study in all sorts of yellows; and "Blue Tiles," seen in a shop window, call up to her fancy the Persian blue of Babylonian palaces. Indeed, she is apt to throw her palette into the picture-grey, moth-grey, stone-grey, snaky-grey; yellow, cowslip coloured, loquat yellow, grass yellow, saffron, golden amber, and "primrose honey," as well as reds and browns, blacks and whites. Out of such sensuously luxuriant material she can weave a story that is never dull, an exotic story of kings and queens, princesses and gypsy girls, and gentlemen with jewelled swords and sentimental hearts. Nor, is this all. She knows how to handle geographical decorations from the Orient. Of local colour no Australian poet has so great a command. Every bird and bush and flower is named and woven without forcing into her poetry. Her verse might have for its sign peacock with all its feathers up,under a rainbow. Her images have often the fanciful conceits of Donne.

The mice of the Dark have nibbled the moon,Where it lay on the shelves of day.

As for metrical cleverness she has little to learn from Masefield's "Cargoes" when she writes of Sydney streets. To read a volume of Mrs. Forrest's poems is to feel yourself squatting in some Eastern palace on rugs of wondrous dye, with all the perfumery and cruelty of a Sultan's divan around you as you look from a lattice or a spicy garden of the Golden Horn. But if she surrounds herself with Oriental splendour, her ear is never dull to the still, sad music of humanity. How poignant her "Old Woman," in "Alpha Centauri," and "Old Men," in the "Poems," are every reader knows. And in the later poems (not yet published in book-form) this diapason note sounds more frequently and more hauntingly, often in a single final line -- "I shall not need a lamp when I wander among the stars." Mrs. Forrest has been writing since the century began -- essays, poems, and four fine novels, and because she has written much under the spur of necessity, some critics have spoken of "her facile pen." "It costs not much to make a song," she says ironically.

It needs no thews of mighty strength,No treasure fund of gold to sink

Only a pen a dagger's length --

With veil of heart's blood for the ink.

First published in The Courier-Mail, 30 September 1933

[Thanks to the National Library of Australia's newspaper digitisation project for this piece.]

Barnes had previously been shortlisted for Flaubert's Parrot (1984), England, England (1998) and Arthur and George (2005).

You can read the full list of shortlisted, and the longlisted novels.

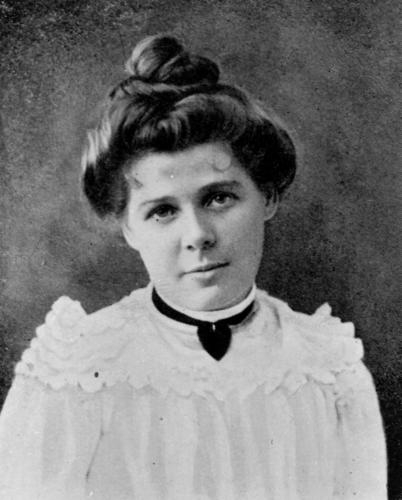

Mabel Forrest (1872-1935) was born on the Darling Downs in Queensland. She was, in the main, home-schooled by her mother as the family moved from station to station, following the father's managerial work. She married John Frederick Burkinshaw in 1893 but the marriage was an unhappy one - with Burkinshaw moving to Perth in 1896, and the couple being divorced in 1902; she married John Forrest a few months later. She had begun writing during her first marriage and her prolific output was maintained up till her death in Brisbane in 1935.

Author reference sites: Austlit, Australian Dictionary of Biography

See also.

Mrs. Mabel Forrest, the Queensland poetess and authoress, whose works have had appreciative recognition in and beyond Australia, died early yesterday morning.

Mrs. Forrest had experienced indifferent health for several years, but continued her prolific literary output without impairment of her grace of style and vigour of thought. Paralysis of the right arm supervened on a fracture of the shoulder, caused by an accident about 12 months ago, but she bore her suffering with fortitude and cheerfulness.

Mrs. Forrest's early life in the country and experience on stations, amid bush-bordered lands or on the plains, was reflected in much of her work. She was the daughter of the late Mr. and Mrs. Mills. Mr. Mills was well known on Darling Downs and South western grazing properties, including Marnhull and Callandoon. She was born near Yandilla, and she also lived in Goondiwindi and Dalby. Later she lived in Townsville and Charters Towers, amid the contrasting conditions of the North.

VERSE AND PROSE

Most of Mrs. Forrest's books bore alliterative titles. Her first novel to be published in London, in 1924, was "The Wild Moth," later screened as "The Moth of Moonbi." It ran into three editions in London. Other novels were "Gaming Gods," "Hibiscus Heart," "Reaping Roses," "The Bachelor's Wife" (published in 1912, and the prelude to success in prose), "Carlotta," "The Scythe of Fate," "Topaz Eyes." Among her verse was "Alpha Centauri" and "The Rose of Forgiveness" (1909), "Streets and Gardens"' and "The Green Harper." Some of her books first appeared as serials and these, as well as short stories and verse, were accepted by many Australian and English newspapers and magazines.

Several of her short stories were translated into Dutch and published in Holland. She won 14 prizes in literary competitions. Her writing began in her seventh year. In her country home she scribbled her thoughts on backs of envelopes and any piece of paper at hand. While other children yearned for toys she begged Santa Claus to bring a "big book, full of blank paper." She even wrote on a white-washed chimney with a piece of charcoal.

So much of Mrs. Forrest's work was redolent of the bush and the open spaces, of the tribulations and the triumphs of the men on the pastures and the farms, of the spirit of the country, and there was such understanding and sympathy in her description of scene and incident, that she was often thought to be a man. The Society of Authors, inviting her to membership, addressed her as "M. Forrest, Esq." She had been mistaken for a mine manager and a cattle and a sheep station owner. A Frenchman of letters, Henri Corbiere, appreciating her "The Heroes," written in war time, wrote to her longing to "shake mon ami by the hand."

Many notable English poets and authors wrote to her in tribute to her work. She was a member of the Society of Authors (London), the Fellowship of Australian Writers, the Lyceum Club (London), and a life member of the Queensland Press Institute.

The remains were cremated at the Brisbane Crematorium yesterday afternoon.

First published in The Courier-Mail, 19 March 1935

[Thanks to the National Library of Australia's newspaper digitisation project for this piece.]

Last Drinks by Andrew McGahan, 2000

Cover design: Nada Backovic

Allen and Unwin edition 2000

The winners were:

Best True Crime Book

Murderer No More by Colleen Egan

Best Children's/Young Adult Book

A Girl Like Me by Penny Matthews

Best Adult Novel

Cold Justice by Katherine Howell

Readers' Choice Award

The Old School by P.M. Newton

The world to me a shambles is:

Where Butcher Death doth make an end,

Alike of smile, and sneer, and kiss.

He lifts his pole-axe o'er the tall,

And bloody end he gives to all.

Two months ago he killed a mate

Away in far Nyassaland;

Three months agone the Axe of Fate

Laid low, upon the Torres sand,

A man whose life was all too brief --

A trusty pilot of the Reef.

One passed his checks at Hobart Town;

One threw the seven in Papua;

One slung his alley in to drown;

One sinned and burst by Burnett Bar;

Pluck palpitatlon was one's fate;

One turned it up in Foveaux Strait.

And, taking now a stitch in time,

And Chronos by the Foreloek (such

Old metaphors do make for rhyme,

And don't obscure the meaning much),

Of all my friends whom death must seize

I've written the obituaries.

Some are in prose, and some in verse;

On all their virtues I enlarge;

With song I cover up the hearse,

With lyrics deck the funeral barge.

A centenarian (what is truth?),

I weep because of my lost youth!

The friend who drinks in glee to-night!

I'm ready with his earthly end;

My muse with bombazine bedight

(I'll show you how to plant a friend)!

Ere yet the breath has left his clay

His funeral ode shall see the day.

But when I've finished all my pals:

When dead are all the men I knew:

When worms --- Death's grisly seneschals ---

Have hid them all from fleshly view;

I'll vainly search on land or sea

For one to write an ode on ME!

And as I could not quietly

Stay in my grave unless 'twere done;

I state now, without hope or fee,

How good it was ere Time was run;

Careless of blame or praise or laugh

I write here mine own epitaph.

IN MEMORIAM RANDOLPH BEDFORD.

Died 31st Dec., 1968.

When all his virtues I record,

The manly act -- the pregnant word --

And think how good he was and wise,

The salt tears well into mine eyes.

Tall, golden-haired, and debonair ---

(A duke from penny novelettes)

The Bow Bells Decorative Heir --

(The one who always paid his debts).

His blue eye challenged, to outshine,

The sun, his golden hair flowed down

His shoulders -- generous and fine

Of Nature's King the Native Crown.

Quiet his mind, and calm as death;

No impulse swayed his equal days;

He ever drew the equal breath;

And walked in clear, unclouded ways.

A writer he --- a poet great --

(His metres, envy said, were rude);

Great novelist --- tho' 'twas his fate

By critics to be labelled crude.

A statesman he (or would have been),

Master of Witanagemotes;

A salved Australia you'd have seen,

But --- he polled insufficient votes!

But for that trifling circumstance,

A greater, grander Hampden, he;

But smaller men achieved the chance,

Lost by that mere discrepancy.

Hampden and Shakspeare rolled in one,

He might have been ! ('twas not to be be!)

Oh great heart hidden from the sun

With gold broad-barring all the sea!

He might have been --- well, anything!

Napoleon, Dante --- aol that lot!

He might have Caesar been, or King!

Alas, alack! But he was not.

He might have been an Orangeman!

Rejoice an early death his fate

Saved from disgrace by that last ban --

His young life ends at ninety-eight.

He might have been a councillor!!!

Kind death has driven away our fears;

He's saved from being a mayoral bore --

The thought gives gladness to our tears.

He loved to walk the earth around,

Sauntering the world, and up and down

The forests that the deep seas bound,

And wearied quickly of the town.

Rest deep then, Randolph! Rest for long!

Tho' rest to thee will be a pain;

And when the boys, with jest or song,

Come to thy grave, then rise again.

When tremulous, the earth's green breast

Grows with the clamant life of Spring,

In your best Sunday bones rise, drest,

And roam the bush, and have your fling.

Where bony youth and grisly wench

Foot it in Bacchanal, and pass

Each other by the narrow trench

That is their home below the grass!

* * * * *

All of my friends may me forget!

What need have I of friendship now?

When this my dirge is writ, and set

To wait the chilling of my brow?

When life becomes but lees and draff

I'm ready for my epitaph!

First published in The Bulletin, 28 May 1908

A correspondent writes that I should accept "the English language as spoken in the country of its origin," and asks if I want English as spoken on the Barcoo or in Surry Hills (Sydney).

The language of the Barcoo is direct English without affectation, though often illuminated; the English of Surry Hills used to be that of Cockaigne at the Antipodes, and is now rapidly becoming direct English, also without affectations.

English "as accepted in the land of its origin" covers a hundred dialects, and some of the worst affectations of the language. The dialects of Yorkshire, Lancashire, the Midlands, Devon, and Cornwall are not attackable. The patois of the Breton village and the provincialian of the Auvergnat are still French; Piedmont and Sicily speak Italian, though not the Italian of Tuscany; and similarly, though some Lancashire talk may be almost unintelligible to the stranger, it is still English of a sort. The Scotch speak in English with all the differences of men talking in an alien tongue; the wit and imagination of the Irish has made a richer English for Ireland. Whoever invented Welsh must have had as building material the ruins of many aboriginal dialects.

"Announcerese"

Where language or its idioms are natural, objections are almost pedantic, but the interests of beauty, as of truth, are served by objection to the dishonesty of affectation -- objection to the mental falsity and petty vanity that produce it. It was to that mental falsity and petty vanity that I alluded in objecting to the affectations of "Announcerese"-- such verbal horrors as "suparia" for "superior," "marely" for "merely," "par" for "power," "fah" for "fire," and a weather report as "clardy with shahs" for "cloudy with showers." My reference was to the "Announcerese" of the A.B.C., for the reception of B.B.C. radio is rarely good enough to make criticism sure; often mixed with static that disguises voices which clearer reception would enable me to identify as adenoidal.

But this week the B.B.C. reception was clear enough for me to hear the announcer -- a lady -- say that a talk on the Italian-Greecian situation was one jf the best "sairies of the Ar" -- meaning "series of the hour." It is a silly affectation even in London where the "silly ass" of Wodehouse language has replaced English in the West End, and for its copyists.

Compared with the Wodehouse dialect with its spurious cheerfulness and its humour manufactured with great difficulty, the language of the East End is honest and direct. English is not English where it has preferred sentences of "untin' and shootin' an' fishin', an' rippin'," and a direct people, as the Australians mostly are, must not permit themselves that affec- tation which is the lowest form of play acting.

Correct English

Of English speech as accepted in the land of its origin there are the examples of the clean unaffected diction of people in high places. Nothing more natural than the voice and diction of ex-King Edward VIII.; no more natural human speech was ever made than the present Duke of Windsor's declaration of abnegation and abdication. The King, though short of Edward's voice quality, speaks excellent direct unaffected English, and so does the Queen; Churchill's English is also forthright and correct -- marred a little, I think, by an occasional inflection, suggesting the slight unreality insep- arable from the histrionic sense.

But the insincerity of affected speech -- the encouragement to assuming a part -- to play acting in private or public life -- is its own condemnation. And seeing that radio enters the home and can scarcely be shut out of it, one must ask "is it likely that any child seeing the written word 'power,' and hearing it announced 'par' can get the best results from the day's educa tion discounted by the evening's entertainment?" It extends the number of mentally false people -- because there will also be imitators of affectations which are mainly the expressions of frustrated vanity, seeking a protective compensation; and of an impudent vanity that can say what it likes to the customers without fear of the customers talking back.

Met An Irishman

These affectations are also insults to men and women who know and love the language. In "Explorations in Civilisation," I laughed over an Irish man I met at Cogers Hall, off Fleet Street. Said he, "Y'have Tennyson -- the perfection of the sinses. Look at his nose. He cud shmell better than any other man. Says he:

"Me very heart faints an' me whole soul greeves

At the moist rich shmell of the rotting leaves

An' the fading edges of box beneath

An' the breath of the year's last rose!"

'"e cud shmell all that -- rotting leaf and fading s'rub an' dying rose. And or his ear-- man! for his ear."

"Shwate is thy voice; but every sound is shwate

Myriads of riv'lets hastening thro the lorruns;

The moan of doves in immemorial allums;

The murmurst of innumerable bees,

Tennyson the perfection of sound."

An honest, sincere, and direct version. Now imagine Banquo's speech before Macbeth's castle, translated to "Announcerese"-- and note the destruction of beauty by the affectations of the cousin Slenders of the Radios.

This guest of Summah

The Temple haunting Martlet does approve

By his loved Manshonray, that the heavens breath

Smells wooingly ar; no jutty, frieze, buttress

Nor coigne of varntage but this bird hath made.

His pendant bed and procreant cradle

Whar they most breed and haunt I have observed

The ar is delicate.

All men who love English at its best -- the English of Shakespeare, Carlyle, and Tennyson -- must take the affectations that have always discounted its beauty, the affectations that have a larger spread because of their greater distribution by radio.

All language is the correct language; any idiom the correct idiom that has decency and directness; that does not stoop to play act -- a detestable quality always when off stage. More correct than the Wodehouse language and its sedulous apes in Australia are the pidgin of the Papuan, who is direct and tells his story in the fewest words possible, and with the highest literary quality, simplicity, and forthrightness. In the early days of Coolgardie I knew Chief Shaw, who was Mayor of Coolgardie and of Adelaide at the same time. He would be his Goldfields Worship this week and then by coach to railhead, train to Albany, and ship to Glenelg, he would become Mayor of Adelaide again.

In the days when he used to go to bed at least three times in a week, Chief Shaw gave a Mayoral ball at Adelaide Town Hall. At 5 a.m. the Town Hall ran dry; and the lads of the village adjourned with Shaw to the bar of the Old Napoleon.

"Ball go off all right, Mr. Shaw?" asked the barman.

"My oath it did. About half-past two this morning Lady ---" (wife of the then Governor) "came to me and smacked me on the back and she said 'So help me God, Jim! this is the best blanky hop I have seen in 20 blanky years." Of course, what the lady did say was, "It has been a charming dance, Mr Shaw."

Probably even the ribald version was better than the affected translation.

First published in The Courier-Mail, 16 November 1940

[Thanks to the National Library of Australia's newspaper digitisation project for this piece.]

Randolph Bedford (1868-1941)

To those who knew him well the late Randolph Bedford was a big-hearted, genial friend; to many others he was an enigma, and to many thousands he was a legend. That is precisely as he wished it to be.

Mr. Bedford became ill while visiting Sydney and returned to Brisbane last week to take a rest of several weeks in hospital ordered by his doctor.

A prolific writer in prose and verse probably the last literary contribution from his pen was a long, patriotic poem, "Voices of the Brave," which was published in "The Courier-Mail" on June 28.

It contained the following verse, which struck a note of sympathy and resolve in the heart of every loyal Australian:

Oh! My brothers! Labour soldiers in the mine, and forge, and mill,With yet another turning of the lathe and of the drill;

Each precious minute salvaged from the avid sink of time

May save another soldier and avert another crime.

No faint heart can be here, if but we steel the soul and will;

No laggard here to help the foe of all the world to kill.

Mr. Bedford was a remarkable man, mentally and physically big, with a manner that presented him in a full, life-sized setting in most things that he said and did. He was essentially a fighter, with a blade forged and chilled in the battles of more than half a century, and he loved an adventure.

He was born in Sydney, but at 16 he was in the western districts, and at 17 he began to tread the Inky Way at Hay, in New South Wales. From there he went to Broken Hill, when it was mostly an ill-formed canvas town, to a position on the Broken Hill "Argus," which had just started publication. Broken Hill, only three years in development when he went there in 1888, was a rough place, and it was there he developed his love of mining fields and mining speculations.

At one time or another Mr. Bedford had been on every mining field in Australia and New Guinea.

At 18 be had his first short-story published in the "Sydney Bulletin." That was enough; he decided that he would earn his living as a writer, and, with the exception of a brief period on the Melbourne "Age" as a reporter, he did so for many years. The mining fields gave him ample material, and he probably wrote more short stories than any writer in the Commonwealth, several plays (some of which were produced), a travel book, entitled "Explorations in Civilisation," and four novels, the two most popular being "True Eyes and the Whirlwind" and "Snare of Strength," both published in the nineties.

In October,1917, after spending three years in Italy and Mediterranean countries, he entered political life in Queensland as a member of the Legislative Council. He remained there until the council was abolished (one of his objectives in going there); and in 1923 he was returned as Labour member for Warrego, which constituency he represented until his death.

Mr. Bedford loved the storm, frequently raising one as he lashed his opponents with an eloquence and wit that was never excelled in the Parliament of his days. He gave no quarter and certainly looked for none. He was a big square block of a man, with a voice that detonated. He could talk in a whisper or raise his voice to a bellow, and he frequently silenced an inter- jector with a witticism that came like the flash of lightning.

In a tight corner he was Labour's most vigorous fighter, but never reached Cabinet rank, probably because his colleagues realised that in politics he was much happier in the hurly-burly of battle than in a friendly discussion.

In 1937 he resigned his seat to contest the Maranoa Federal constituency against Mr. J. A. J. Hunter. He failed to dislodge the old Country Party representative, and returned to the State House as member for his old constituency of Warrego.

He was a man of undoubted ability, but he was too impulsive, for success in politics for he never learned to suffer fools gladly. He was impatient, and the secret of success in nolitics is to know how to wait in patience. That is a qualification that he boasted he did not possess.

With his death goes a good and vigorous Australian.

First published in The Cairns Post, 15 July 1941

[Thanks to the National Library of Australia's newspaper digitisation project for this piece.]

Shearers' Motel by Roger McDonald, 1992

Cover illustration: Geoff MacQualter

Picador edition, 1992

From the land of Captain Cook;

I opened it up with a loud "Hooray!"

For here was the "Banjo's" book.

'Tis many a day since the "Banjo" strings

Were touched to a tune of my heart,

And work and war and a thousand things

Have wafted us worlds apart.

But I can go back when my eyes are shut

To that hour in the long-lost time

When first I heard in a Darling hut

The ring of a "Banjo" rhyme.

Those were the days when a boy's heart beat

To the rhythm of life and love,

To the music drummed by a horse's feet

And fifed by the wind above.

And I'm glad that his book got through all right,

Unsunk by a submarine,

For "Banjo" and I can be mates to-night

As we go where our hearts have been.

First published in The Bulletin, 12 July 1917

Mr. A. Paterson, the "Australian Kipling," has met the other Kipling. In the S. M. Herald he gives this account of it:--

While in town (Bloemfontein) inquiring into a certain matter I had the luck to meet Kipling. He has come up here on a hurried visit, and partly in search of health after his late severe illness. He is a little, squat-figured, sturdy man of about 40. His face is well enough known to everybody from his numerous portraits, but no portrait gives any hint of the quick nervous energy of the man. His talk is a gabble, a chatter, a constant jumping from one point to another, and he seizes the chief idea in each subject unerringly. In manner he is more like a business man than a literary celebrity. There is nothing of the dreamer about him, and the last thing one could believe was that the little square figured man with the thick black eye- brows and the round glasses was the creator of "Mowgli the Jungle Boy," of "The Drums of the Fore-and-aft," and of ''The Man Who Would be King," to say nothing of Otheris, Mulvaney, and Learoyd, and a host of others. He talked of little but the war and its results, present and prospective. His residence in America has Americanised his language, and he says "yep," instead of "yes." After talking some time about Australian books and Australian papers he launched out on what is evidently his ruling idea at present -- the future of South Africa. " I'm off back to London," he said, "booked to sail on the 11th. I'm not going to wait for the fighting here. I can trust the army to do all the fighting here. It's in London I'll have to do my fighting. I want to fight the people who will say the Boers fought for freedom -- give them back their country!' I want to fight all that sort of nonsense. I know all about it. I knew this war was coming, and I came over here some time ago and went to Johannesburg and Pretoria, and I've got everything good and ready. There's going to be the greatest demand for skilled labor here the world has ever known. Railways, irrigation, mines, milk, all would have started years ago only for this Government."

I asked what sort of Government he proposed to put in place of the Boers.

"Military rule for three years, and by that time they will have enough population here to govern themselves. We want you Australians to stay over here and help fetch this place along."

I said that our men did not think the country worth fighting over, and that all we had seen would not pay to farm, unless one were sure of water.

"Water! You can get artesian water at 40ft any where! What more do they want!"

I pointed out that there is a vast difference between artesian water which rises to the surface and well water which has to be lifted 40ft. When it comes to watering 100,000 sheep one finds the difference.

"OH, well," he said, "I don't know about that; but, anyhow, you haven't seen the best of the country. You've only seen 500 miles of Karoo desert yet. Wait till you get to the Transvaal!"

"Will there be much more fighting, do you think?"

Well, there's sure to be some more, and the soldiers want to get their money back."

"How do you mean, get their money back?"

"Get some revenge out of the Boers for the men we've lost -- get our money back. The Tommies don't count the lot captured with Cronje at all. They're all alive and our men are dead. We want to get some of our money back. You Australians have fought well," he went on; "very well. Real good men. Now, we want you to stay here and help us along with this show. I can't understand there being so many radicals in Australia. What do they want? If they were to become independent, what do they expect to do? Will they fork out the money for a fleet and a standing army? They'd be a dead gift to Germany if they didn't. What more do they want than what they've got?"

I didn't feel equal to enlightening him on Australian politics, so I said, "What are you going to do with the Boers if you take their country?"

"Let 'em stop on their farms."

"Won't they vote against you as soon as you give them the votes back? Won't they revert to their old order of things?"

"Not a bit. We'll have enough people to outvote 'em before we give 'em the votes. There'll be no Irish question here. Once they find they're under a Government that don't commandeer everything they've got, they'll settle down and work all right. They're working away now to the north of us, entrenching away like beavers; we'll give them something better to do than digging trenches."

One could almost see the man's mind working while he talked, and yet all the time while he was talking with quick, nervous utterance of the great things to be done in those unsettled countries I seemed to see bebind him the heavy, impassive face of the man I saw in Kimberley -- Cecil Rhodes. Kipling is the man of thought and speech, Rhodes the man of action. Cecil Rhodes seems to own most things in these parts, and when our Australians reach the promised land of which Kipling speaks so enthusiastically they will be apt to find the best claims already staked out by Cecil Rhodes and his fellow-investors -- at least, that is my impression. There are no fortunes "going spare" in this part of the world; but, anyhow, this is not a political letter, and Kipling is big enough to draw his own rations, and if he chooses to temporarily lay aside the pen of the author for the carpet-bag of the politician, it is his own look-out. He expressed great interest in the Australian horses, and promised to come out to the camp and see them, and he gave us a graphic account of the way in which an Australian buckjumper had got rid of him in India. "I seemed to be sitting on great eternal chaos," he said, "and then the world slipped away from under me, and that's all I remember."

He looks pale and sallow after his illness, but seems a strong man, one that will live many years if his brain doesn't wear his body out.

First published in The Sydney Morning Herald, 12 May 1900, and later extracted in The Barrier Miner, 17 May 1900.

[Thanks to the National Library of Australia's newspaper digitisation project for this piece.]

A.B. "Banjo" Paterson (1864-1941)

There is scarcely a corner of Australia in which the author of "The Man From Snowy River" was not known -- if not personally, at least by his verse -- and it mattered not whether he was among the sheep Outback, at the station homestead or in the shearing shed, or in the shearers' hut; at an up-country race or polo meeting; or on any field of sport; or fishing in his beloved Snowy River; or even on active service (he had three campaigns to his credit); "Barty" was always a fine fellow.

He loved Australia, and his verse, unlike that of many other Australian authors, was never morbid. He saw the best in his native country, and he had a keen sense of humour, which was equally apparent in his conversation and in his writings. Paterson will be numbered among the great Australians, and one test of his qualities was that one never heard him referred to as "Mr, Paterson." It was always "Banjo" or "Barty," which was as he liked it.

A son of the bush, which he loved. Paterson was bom at Narrambla, near Molong. After leaving the Sydney Grammar School he studied law, being subsequently admitted as a solicitor. For some years he practised his profession in Sydney, and was a member of the firm of Street and Paterson. He was not keen on the law, but he found time to combine with his legal work, as one writer has expressed it, "the writing of cheerful verse inspired by the life of the plains and hill stations." At every opportunity he got away to the bush.

Good-bye to Drudgery.

Eventually the pen triumphed over the law, and Paterson forsook what was to him the drudgery of the lawyer's office for Press work, which provided greater opportunities for a life in the open. As an editor, however, he was to a great extent out of his element, for, although newspaper work appealed to him, the administrative duties involved in these positions were not at all to his liking.

Paterson always had a warm spot in his heart for the horse. If Shakespeare had not put the words, "A horse! A horse! My kingdom for a horse!" into Richard Ill's mouth, it is more than likely that Paterson would have uttered them. He dearly loved a horse -- a good horse -- and to have deprived him of his "horsey" talk would have deprived him of one of the pleasures of speech. Whether it was the most famous colt of the day; whether it was the slickest polo pony ever bred; or one of the wild horses of which he sings in his verse was all one to "The Banjo."

His thoughts were ever in the country. On one occasion he dryly remarked to the writer that he was going to spend a holiday with the sheep out west, and that about summed up Paterson's temperament. Sheep out west meant horses to muster them, and there "The Banjo" would be happy.

In those days Paterson's nerve and dash made him one of the best of amateur riders, and he was a frequent competitor at the meetings of the old Sydney Hunt Club. He was also a polo player of ability, and was keenly interested in the turf. Up to within a few weeks of his death he was a conspicuous figure on the principal racecourses of Sydney, with his outsize in field-glasses. At one time -- in the early years of the present century -- he essayed the ownership of racehorses, but did not meet with any great success. Paterson was a keen tennis and bowls player.

His verse will live long -- particularly in "the bush" -- for its cheerfulness and expressiveness, and for its description of the brighter side of Australian country life.

First published in The Sydney Morning Herald, 8 February 1941

[Thanks to the National Library of Australia's newspaper digitisation project for this piece.]

Mr Darwin's Shooter by Roger McDonald, 1998

Photography: Petrina Tinslay. Design: Gayna Murphy/Greendot design

Knopf edition, 1998

|

Sara Warneke (better known by her pen-name Sara Douglass) has died at the age of 54.

Born in Penola in South Australia she attended school in Adelaide and became a Registered Nurse before studying early modern English History at the University of Adelaide. She later became a lecturer in medieval history at la Trobe University in Bendigo, Victoria. She wrote a number of novels without success before trying her hand at fantasy and being signed to HarperCollins Voyager in 1995, a fantasy publishing list that has flourished over the years, most probably as a direct result of the huge success that Douglass achieved. Over the years she published 20 novels and received a number of awards in the Australian fantasy field. She died in Hobart on September 26 of ovarian cancer. |

Obituary by Lucy Sussex in The Age.

Digital Narrative Encouragement Award

The Garden, Robin Craig Clark (Peliguin Publications)

Non-Fiction

A Three-Cornered Life: The Historian W. K. Hancock, Jim Davidson (UNSW Press)

Fiction

That Deadman Dance, Kim Scott (Picador Australia)

Scripts

Gwen in Purgatory, Tommy Murphy (Currency Press)

Children's Books

Toppling, Sally Murphy (author) and Rhian Nest James (illustrator), (Walker Books Australia)

Poetry

Fire Diary, Mark Tredinnick (Puncher & Wattmann)

Young Adults (Joint Winners)

Anonymity Jones, James Roy (Random House Australia)

and

Happy as Larry, Scot Gardner, (Allen & Unwin)

State Library of Western Australia WA History

Vite Italiane: Italian Lives in Western Australia, Dr Susanna Iuliano (UWA Publishing)

People's Choice Award

Utopian Man, Lisa Land (Allen & Unwin)

Premier's Prize

That Deadman Dance, Kim Scott (Picador Australia)

It is complete -- the magnum opus finished.

My book is writ; its joys shall be my own --

These none shall share. Delight is undiminished

In that I revel selfish and alone.

Each line, as written, stands for anxious thinking;

No pencilled sign was casually made.

At times my very soul with fear was shrinking;

Again, I'd write a line and pause dismayed.

Here should be tears -- I wrote this line in sorrow --

Here deeper grief, for much was put at stake;

Oft have I wished each day was its to-morrow,

Oft slept with Fear -- with Care to mate, awake.

At length the end; I wrote in desperation

To simplify the tangle in my skein,

And finished with a powerful situation --

Finale -- in my very happiest vein.

No linotypist's inky paws shall fumble

The pages of MY BOOK. No printer scoff

At my poor penmanship; no reader grumble,

And wish I had been, timely, taken off.

The sacred pages only I shall study;

And I for Recollection's joy alone

When I would have the reds of Life more ruddy,

And realise a pleasure shared by none.

I'll read again the writing, in the double-book I made; ten thousand was the limit, and one horse I hadn't laid (for the cognoscenti knew him, and he had no chance, they said; where the quick were under saddle, he was listed with the dead). But he cantered home the winner of the second big event, and I motored home a "skinner" - wherewithal I am content.

First published in The Bulletin, 25 January 1917

It is only when we get the verse of Louise Mack (it is not possible to be conventional and call her Mrs. Creed) collected under one cover that we realise what a loss to Australian letters was her departure for England. Not that she is now a great poetess -- it were too early to expect that -- but there is in all her work a hint of higher things to come, when she shall have shaken off the subjective method and explored the wider, freer realms of the objective. For her poetry, so far as this booklet is concerned, is almost purely personal, her own impressions scored in a minor key, with the dominant note always that of the aching pain of unfulfilled dreams and ideals. She is a worshipper of nature, and she fits the moods of the great earth-mother to her own thoughts -- and they are sad ones. Sometimes her own grief is emphasised so much that it jars on the sensuous enjoyment of her melodies; but more often she has caught the happy mean, and her stanzas breathe tones of sadness and regret that are common to all mankind. But she has an undoubted gift for assimilating the sombreness of our Australian landscapes, the gladness of our Australian skies, the gloom that hangs pall-like over our Southern scenes on occasions, and giving them forth again to her little world clothed in language tinged in the process of reconstruction into pen-pictures, with her own natural trend towards pathos, and with her own desire to turn the commonplace into the beautiful, or even the fantastic. And usually she tries, too, to bring human beings and human passions into closer touch with the natural, and in so doing she lifts them to loftier planes. There are few verses of hers that are perfectly free from the human element, but of the few here is an example from "Leaf Music":

Listen! the winds are playingA fugue in the orchard trees;

They creep through the boughs of apple,

And linger among the leaves,

And touch with a gentler straying,

Leaves over soon decaying.

. . . . . .

The winds come sighing, singing,

Through leaves with a silken sheen

This song is a silver treble,

With an alto note washed in;

But she touches us more nearly with her tragedy, whether it be her own, or, as in "The Wharf," imaginative. She is so deeply in earnest, has so many aspirations that she has failed to attain, can reconcile so little her own life to that she would choose to live. There is in her work, from this aspect, a passionate sub-thrill of emotion, straining after the higher things of existence, or plunged in despair because they are beyond her reach. Hers is no ordinary chafing against the limitation of surroundings, no light protest against the confines of soul. Her one wish is expressed herein :

With a song, unbound and fetterless

With a gush of song in the throat,

Loosened and loud and letterless,

And the wind its only accompaniment.

. . . . . .

Sudden and swift some day

Meet Death, and have no fear of him;

But close the eyes and have done.

.... When a bird dies none hear of him.

He has sung and ceased, and is happiest.

And because that is withheld from her, her verse takes on the bitterness in which she steeps her love poems, the poems in which passion is checked by the force of circumstance, where love suffers and is assuaged. This theme she has attempted many times, and mostly with success; but she is even better when she sums up the whole of life's griefs, and decides that they are after all naught when compared to the restfulness of the afterworld. Perhaps her best work in the book is her long poem, "To Darkness," which is sonata-like in form. There is little that is more expressive and at the same time exemplifies her typical mood better than this verse, which concludes one of the "movements":

Night, will you hear as I lie at your shadowy gate,And, silent, silent wait for your perfect breast?

Night, will you know, though my Wandering Heart is late,

It is yours at last, and is yours for ever?

Little Dawn and the Middle Morn,

And Moon and Sun, I have left them all,

For the tireless peace of your passionless thrall.

Or in this from another poem:

Oh, the sweet of lying still!Of lying still and still, long year on year.

Wild overhead lives throb and thrill,

Waves beat the shore, and winds the hill,

But only silence ever enters here.

There remains yet the best of her "human" poems, where she has set two hearts apart to watch their struggles towards reunion. There is something that touches one strangely in her verse of this description. It is not that the poems show any mark of genius. They are ofttimes only ordinary, but the pulse of feeling beats so strong, the chord of sadness rings so true, that one is constrained to remember and admire. And then there is her patriotism, her love for the city of her sojourn, the land of her birth. There are dainty little pictures in monochrome on every page, studies in gray that arrest the attention, and cry aloud for the quotation that space forbids. Louise Mack is a poet whose work must be read not once or twice, but many times, and every time her lines are scanned new beauties will spring into being. She has her faults, of course there are inaccuracies of rhyme and rhythm that are left unpolished, but there is the saving grace that her poetry is warmblooded, throbbing with elemental joys and sorrows. She has been original, keen in psychological analysis where that was necessary, and has broken loose from the fetters that usually bind the woman in poetry. Her booklet of verse is a thing that will be cherished by all Australian dilettante, because it is the only memento we have of one of our cleverest litterateurs, and in time, when its charm has sunk deeper, when the lines have been read until they are implanted in our memory, Louise Mack will be remembered as in her "Before Exile" she asks to be.

This is my last good-bye,This side the sea;

O, friends! O, enemies!

Love me, Remember me.

Farewell! and when you can,

Love me, Remember me.

First published in The Brisbane Courier, 22 June 1901

[Thanks to the National Library of Australia's newspaper digitisation project for this piece.]

Louise Mack (1870-1935)

Author: Marie Louise Hamilton Mack (1870-1935) was born in Hobart and moved from state to state with her Wesleyan minister father before settling in Sydney where she undertook her secondary education. A friend of Ethel Turner she started writing poetry for The Bulletin in the late 1880s. She married in 1986 and left Australia for England in 1901. After living there and in Italy she was the first woman war correspondent in Belgium in 1914. She wrote several novels and travel books along with her poetry, and died in Sydney in 1935.

Author reference sites: Austlit, Australian Dictionary of Biography

See also.

Louise's lines:

I am dead, dead tired of living,I am tired of everything.

Tired of getting, tired of giving --

Tired of winter, tired of spring.

The never-to-be-forgotten "Teens," the apotheosis of the Sydney High School girl, became the Bible of all the bright young things who did not then know they were "flappers." They worshipped their spokeswoman. A few years ago when I was on holiday with Louise in Queensland, important matrons were constantly introducing themselves as prototypes of her characters and demanding her autograph.

Early marriage did not interrupt Louise's literary career. Her ambition was unleashed, and London called. Without money and almost without introductions, she went and saw and conquered. Lord Northcliffe recognised her light touch in journalism as just what he wanted, and newspaper work might have claimed her altogether had not the romantic urge persisted. Book after book appeared -- innocuous novels they would be called to-day, but they had their faithful public, the young folk who like sentiment and romance and are not "hard-boiled." Once discussing her "Red Rose of Summer," Louise told me that life in London had often been far from a bed of roses for her. There were days when it seemed that she would have to own herself defeated and return to Australia.

I cannot help telling a story over which I have both laughed and cried. Going, practically penniless, after a vacancy on one of Lord Northcliffe's papers, she had to take a taxi because her shoes were so worn she could not walk in them. She got the job and haughtily told the commissionaire to pay the taxi and put it down to the boss. The man, probably dazzled by the blue eyes and baby face, meekly obeyed.

TYPICAL COURAGE.

That casting all on a die was typical. Courage was the keynote of her character, and "Darkest Before Dawn" peculiarly her motto. She had, her friends are glad to know, years of success and happiness in England, and again, in Italy -- the country of her Instinctive adoption; even if they are saddened by the knowledge that life was not as kind to her as it should have been in her later years.

Then came the war, and, for Louise, further opportunities. I never clearly gathered how she defied authority, which said no woman was to go to the front as correspondent, and just got there. Anyway, some of the finest accounts of events in Belgium appeared over her name. I have often said that she saw more with one eye closed than the average man a-stare. The information that she obtained at first-hand was afterwards enjoyed throughout the length and breadth of Australia in a series of brightly expounded war lectures -- vivid pictures of life as led by men and women in the stricken areas. She came equipped with films which, with the co-operation of the Minister for Education, she showed in most cities and towns of New South Wales.

Of her bright personality, her vitality, her gifts as a hostess, her perennial youth, her passionate love of literature and, above all, poetry -- how to speak? I can only ask in the words of Mary Gilmore:

How shall I remember --With tears? With laughter?

In all the years to come yet after

Let me remember.

First published in The Sydney Morning Herald, 30 November 1935

[Thanks to the National Library of Australia's newspaper digitisation project for this piece.]

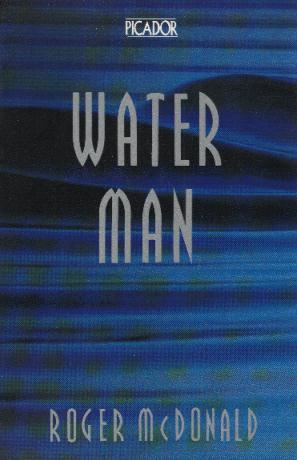

Water Man by Roger McDonald, 1993

Cover photograph: Austral-International

Picador edition, 1993

Of midnight shows her lamp forlorn, to light the late buffoon

Slow homeward from his loyal lodge --- or from the A.N.A. --

To shine on them and help them dodge the trees upon their way,

The pencil-pushers hump it, day by day.

Before the dawn is in the sky, while yet black night is here,

And restless worlds go flashing by to mock the man in beer

Who has his own starred universe within his bleary eyes ---

With many a random, rousing curse as time a-gallop flies,

The pale scribes of the grey bush wake and rise.

Their slow steeds start along the track to meet the dawn, aflame

Far down the skyline, grim and black; some days these nags go lame;

Some days they reef or plunge or kneel ungainly in the mud,

While, slow, the scribe, with clinging heel, slips forward, with a flood

Of threatenings to spill the poor plug's blood.

so, travrelling far, the restless scribe picks shining pearls for print

From council-swine -- gross diatribes and words whose flaring tint

Of turquoise or of purple fills the client one with joy;

He gathers gems from some bucolic cove in corduroy.

(Such little things that cove seem to annoy.)

Weird nights of pothouse banqueting, to toast the cricket club,

Fill up his hours. He haunts alike the chapel and the pub;

The township butcher posts him in the price of beef and chops;

The farmer, with his goat-like chiv., lies to him re the crops --

And! while! he! toils! his! salary! never! stops!

He courts the rectory and the manse each with its little show,

Tea-fight and concert --- no, no dance! --- where all good pressmen go;

And, final straw, the late press-night when, with the blushing dawn,

The scribe goes home with pipe alight, and half his screw in pawn

For beer, his system simply one . . . vast . . . yawn!

First published in The Bulletin, 16 June 1910