Louisa Lawson stamp issued by Australian postal authorities in 1975.

Adelaide. April 3.

Miss Catherine Helen Spence, whose writtings on social and political subjects are known all over the world, died at her residence, Kent Town, early this morning. She was 84 years of age.

The late Miss Catherine Helen Spence, authoress and literary writer, was the president of the Effective Voting League of South Australia, and vice-president of the National Council of Women. She was born at Melrose, in Scotland, on October 31, 1825, and was a daughter of David Spence, writer and banker, her mother being Helen Brodie, who had descended from a long line of tenant farmers in East Lothian. She arrived in South Australia with her parents in November, 1839. Since 1859 the main object of her life was electoral reform -- the Hare-Spence system of proportional representation or effective voting -- in which cause she lectured throughout South Australia and in other States and delivered about a hundred lectures in United States, America, and Canada, and also interested herself in the children of the State. The movement made by Miss C. E. Clark in 1872 to take these out of institutions and place them in family homes was joined by her, and after 13 years' work on the Boarding-out Committee she was appointed a member of the State Children's Council, with which she had been associated since 1886. She was a member of the Destitute Board since 1896. She sat on the Adelaide Hospital Commission in 1895, and was president of the Wo- man's Co-operative Clothing Factory. She held a commission from the South Australian Government in 1893 to inquire into educational, constitutional, and electoral laws, the management of benevolent institutions, and the question of bimetallic currency, especially to take part in the congresses held in Chicago in that year. She had written extensively for the South Australian Press since 1878, more particularly the "Register," and she contributed numerous articles to "Fraser's Magazine," "Cornhill," "Harper's," "Melbourne Review," "Victorian Review," the "Centennial," and other magazines and journals, and she was the author of several works, including "Clara Morison" (a novel in two volumes, 1854), "Tender and True" (two volumes, 1856), "Mr. Hogarth's Will" (three volumes, 1865), "The Author's Daughter" (three volumes, 1867), "Gathered In" (novel), and "The Laws We Live Under, with some chapters on Elementary Political Economy and the Duties of Citizens" (published under the direction of the South Australian Education Department, 1880). She lectured for many years on literary subjects, and filled Unitarian pulpits in Australia and America. She was a candidate for the Federal Convention in 1897 on the one issue of electoral reform, and received 7,500 votes, which were insufficient for election.

First published in Western Mail, 9 April 1910

Note: Catherine Helen Spence died in Adelaide on 3 April 1910.

[Thanks to the National Library of Australia's newspaper digitisation project for this piece.]

Poems, Odes, Songs. By Henry Halloran, C.M.G.

Sydney : Turner and Henderson.

Amid the multitude of Jubilee poems and odes by great and small, those from Mr. Halloran's pen have no unworthy place. There is a vast difference between verse made to order and that which springs directly from a real emotion or feeling. Much that has been written by men of world-wide fame upon the Queen and the Jubilee is tame, unreal, and calculated to make the mind antagonistic to any poetical expressions of the spirit of the time. Not without dread would the critic naturally pick up Mr. Halloran's tastefully edited book of "Poems, Songs, and Odes," dedicated in a sonnet to Lady Carrington, but there is cause to be thankful that there is something worth quoting in this book on this now wearying subject. Lord Tennyson's ode was a dismal failure. Mr. Lewis Morris's was laboured and unmusical, however careful and classical it was in form, and the hosts of others were no better, and principally worse. Where many masters have failed it would be too much to expect Mr. Halloran to succeed, and it would be unjust to him and to the public to say that the peoms are altogether worthy. But there is a reality, a spontaneity, and a genuineness about many of the verses that go far to disarm criticism. There are undoubtedly too many poems of the same kind in the volume, and the old ideas are worked over and over again, but they are evidently the gleanings of many years, and show a continued attitude of loyalty to the throne, as well as many fine thoughts of of a mind accustomed to speak in numbers. The very honesty of the poetical purpose commands respect, and the lines are not infrequent which would not look ill beside the work of greater men. However little one may agree with the excess of feeling which pervades the volume, there is enough that is good in it to merit praise and to entitle Mr. Halloran to a hearing on his theme. The following lines, from an ode on the anniversary of the birth of her Majesty, are indicative of the tenor of the volume and of the musical force that is in it :

"The banners of crimson and gold

|

That Deadman Dance Kim Scott Pan Macmillan 2010 |

Big-hearted, moving and richly rewarding, That Deadman Dance is set in the first decades of the 19th century in the area around what is now Albany, Western Australia. In playful, musical prose, the book explores the early contact between the Aboriginal Noongar people and the first European settlers.

The novel's hero is a young Noongar man named Bobby Wabalanginy. Clever, resourceful and eager to please, Bobby befriends the new arrivals, joining them hunting whales, tilling the land, exploring the hinterland and establishing the fledgling colony. He is even welcomed into a prosperous local white family where he falls for the daughter, Christine, a beautiful young woman who sees no harm in a liaison with a native.

But slowly - by design and by accident - things begin to change. Not everyone is happy with how the colony is developing. Stock mysteriously start to disappear; crops are destroyed; there are "accidents" and injuries on both sides. As the Europeans impose ever stricter rules and regulations in order to keep the peace, Bobby's Elders decide they must respond in kind. A friend to everyone, Bobby is forced to take sides: he must choose between the old world and the new, his ancestors and his new friends. Inexorably, he is drawn into a series of events that will forever change not just the colony but the future of Australia...

Reviews

Morag Fraser in "The Sydney Morning Herald": "That Deadman Dance is a novel to read, recite, and reread, to linger over as Scott peels back layer after layer of meaning, as he slides unapologetically across time and between cultures and ways of being, seeing and understanding. Sometimes his shifts and turns are more boomerang than snake, rebounding, catching you unawares like a sharp key change - exhilarating, disorienting...Scott exploits his ancestry and historical records - songs, diaries, journals, letters - to ground this imagining of early contact. His characters, both Aboriginal and European, are deeply incised, like aunties, uncles, brothers and sisters as robustly individual and cranky as your own (some of them bear the names of Scott's forebears, Manit, Wunyeran and Binyan). Black and white, they stand on ceremony, break rules, break new ground, revert to tribal type, trust, conspire, despair, hope and betray. And there are so many of them that you may need to draw up a Russian novel-style list, with the equivalent of patronymics for the initially bewildering variety of names and languages, spoken and written...There are many strands to That Deadman Dance: epic coastal journeys, whaling sequences that will make you gasp in wonder, injustice, understanding and loss. But it is the characters - flawed, credible human beings, embodying their history but never mere ciphers - who stay with you.."

Martin Shaw for "Readings" bookshop: "Scott begins his tale in the early 1830s, focussing on a fledgling colonial outpost not far from present-day Albany. His narrative follows both black and white, and is divided into several parts, proceeding linearly over a little over a decade, but including as well a prequel of sorts back to the mid-1820s. It is a periscopic style that enables us to observe the shifting perspectives over time among all the participants, newcomer and traditional owner alike, as the 'progress' we know from our history books unfolds...It's hard to imagine we'll ever again have an account of this period, fiction or non-fiction, with such veracity as this, and I mean that particularly in terms of the psychological. For here we get absolutely convincing portraits of the attempts at understanding on both sides."

Patrick Allington in "Australian Book Review": "Scott is an asiduous researcher and a deep thinker. Benang is a feat of storytelling: Scott weaves the complexity and the politicisation of language and the consequences of assimilation policies directly into the prose. But in That Deadman Dance, it is the author's imagination and his graceful prose that shine brightest. Colonisation has prompted in Scott a different imaginative response from the assimilation policies and eugenicist belief systems of early twentieth-century Australia. Although That Deadman Dance does not have Benang's sense of being a landmark book, a sardonic, tottering monument, it is nonetheless the better -- as well as the more accessible -- of the two novels. Politically charged and historically astute, it possesses a furious poise and yet is generous of spirit. Scott avoids gratuitous description, which serves only to heighten the novel's potency."

David Whish-Wilson: "One of the other tangible results of the publication of the book is the fact that, as far as this reader is concerned, 'history' is the richer as the result. Based on solid research (Kim can trace his ancestors to this area, and these stories), and refracted through the mind of a distinctly original writer, 'That Deadman Dance' and particularly its central character Bobby Wabalanginy give voice to not only what was, and what is now, but also to what might have been - serving not only as a reminder that history is always a matter of individual people, and the choices they make, but also the hard truth that the very openness and generosity of the original inhabitants of the area, something that enabled at one point a genuine possibility for intercultural understanding, particularly as it relates to the nature of 'country', was lost (perhaps not irrevocably) precisely because to a large extent the learning and resulting cultural adaption only went one way."

Kim Scott on the "ANZ LitLovers" blog: "It is, as you read, as if all the preconceived ideas of this country's history of Black and White relations fall away and a new paradigm takes their place. What if, Scott asks, the benefits of White Settlement and indigenous expertise were mutual and equally valued? What if there were a genuine friendship of equals? What if the companionship of children grew into adult love across the colour bar? What if the Noongar landlord had been welcome in the houses that the White Man built across his land? And, is it too late now?..Effortlessly, these new ideas insinuate into consciousness. Bobby Wabalangay dances his way through this novel challenging the sourness of the History Wars. He offers a new way of looking at the past and at the future. Scott has the moral authority to play with these ideas because he is a descendant of the Noongar People who have always lived on the south coast of Western Australia where the early whaling settlements were. Like Bobby he speaks both languages and listens in both."

Interviews

Ramona Koval on ABC Radio's "The Book Show".

"Booktopia" blog.

Other

Kim Scott on Youtube:

allowfullscreen="">

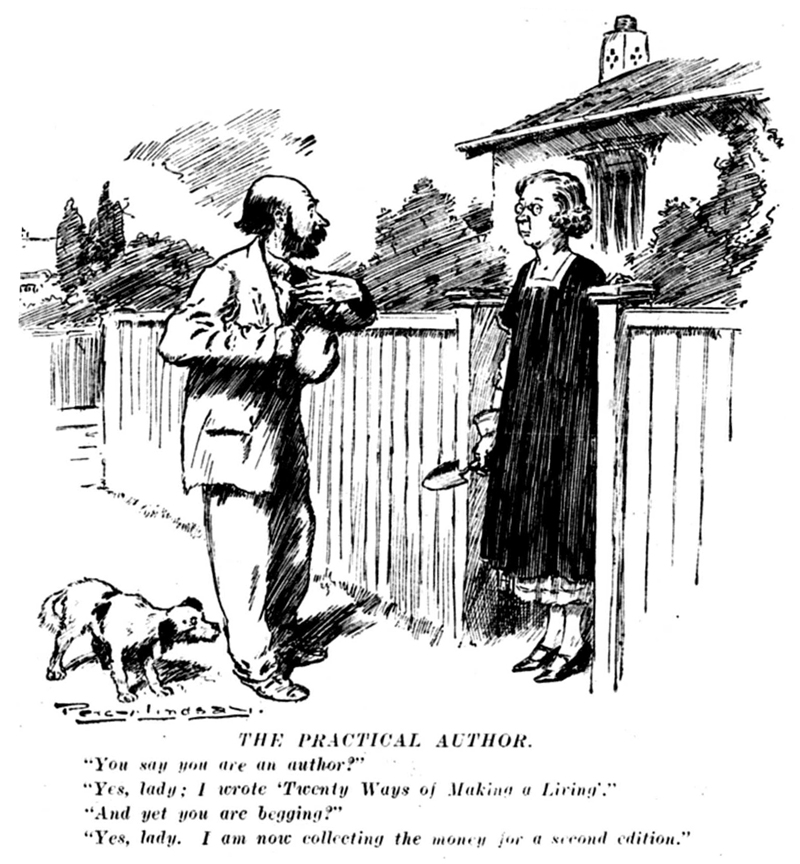

Now that authors' week is over in Brisbane, the very building that housed its proceedings is being demolished like the glass of fervent, Young Lochinvar. ("He quaffed off the wine, and he threw down the cup," you will remember.) Well, what remains? It is interesting, I think, to notice one of the aspects of Authors' Week in Melbourne, and to wonder how the same plan would have gone in Brisbane. The President of the Australian Literature Society in Melbourne suggested a public plebiscite as to the twelve best Australian writers in verse and prose, sending in his own list as a first kite to try the wind. Please notice that the president's original idea was for people to send in lists of the six best writers in prose and verse, and his own list included several well-known names and several that were quite obscure. This was as it should be, since popularity and high quality can only occasionally coincide. No sooner was the stone well rolling, however, than the scheme was of quite a different nature. Every one who sent in a list was sending names of the most popular writers, or, if some comparatively unknown names appeared, it would be because their sender thought they ought to be popular very soon. No room was left for the good but obscure. Thus people were soon contributing rather to other people's preferences than to their own. So-and-so could not well he mentioned because nobody else had mentioned him, which meant that he was not popular. Meanwhile, though, there were the fifty or so who were mentioned at the very first. Their supporters at any rate could not all have believed that they were naming the six most popular poets and novelists in Australia. Some of those first names must have been the utterance of a genuine preference. Let us see what some of these obscure chosen writers can do.

Shaw Neilson.

In one of the first lists sent in, four of the poets were really safe, secured even by having left this world many years ago. I think their names were Brunton Stephens, Kendall, Alfred Domett, and Gordon. These writers are in the textbooks, and can he taken more or less for granted. Even people who never read them will recommend them to you. The remaining two were Hubert Church, the New Zealander, and Shaw Neilson, the Victorian. Neither of these is one of our "popular" poets. Their supporter obviously held them up for their intrinsic goodness. Shaw Neilson and Hubert Church can both endure the fierce light of criticism. What they chiefly suffer from is a complaint well known to our poets, the complaint called neglect. This neglect is not purposely applied, like a draught of poison: People do not say,"X is a bad poet, so I shall neglect him!" On the contrary, they say nothing about X, they have never heard of him, for there are no solid Australian reviews where X is discussed. When his book appears, it gets a few lines of brief notice, probably appreciative, but at once forgotten. Even the name of the book is forgotten, and the name of the poet. And yet, leaving Hubert Church out for this time, Shaw Neilson is an easy name to remember -- John Shaw Neilson. His first volume, published belatedly in 1919, was called "Heart of Spring." Its publisher was the "Bookfellow," ' which means A. G. Stephens, the veteran critic and brilliant journalist, who has never ceased to exalt the name of Shaw Neilson during these twenty-five years and more. "Heart of Spring" in a small but satisfactory edition was widely sold, but not to most of the people who read and follow general poetry. It is doubtful, for instance, if it reached Brisbane at all, so that Brisbane poetry-lovers would have a chance to choose or neglect it. They would not do well to neglect that book. More than most books, it was written with a man's heart-blood. Frail of physique and with failing sight for many years, Shaw Neilson has had to do heavy manual labour such as leaves a man exhausted in his leisure. Yet when his poems take shape, you would say they were the work of some favoured human being, some one enjoying an almost celestial freedom from earthly cares :--

-Listen ! The young girl said. There callsShaw Neilson's poems are not realistic descriptions of the life about him. They are distilled from that life transmuted in the fine chambers of his quiet mind. Perhaps the best whole poem to quote is "May." It is a poem, that reflects the Victorian winter landscape! reflects it in a parable, echoes it in a gentle song -- never "reproduces" it. That is not Shaw Neilson's way.

These are the quiet four stanzas :

MAY.With Neilson's poetry, the surrender has been complete. The poet has grasped the one fundamental reason for making a poem -- that he has something to say for which reasoned prose would be inadequate. What he says would sometimes have no meaning in prose. In poetry, it sings its way into the spirit, doing what prose could never do. He sings again:

Let your song be delicate.Neilson Sung.

These frail, exquisite lines were written as complete in themselves, yet their vowels are so well spaced, and, on the other hand, modern song composers have come to have such a respect, indeed, such a passion, for sheer poetry, that it has been possible to set some of Shaw Neilson's finest lyrics to music. Dr. Whittaker, the well-known English musician and choir-leader, has done this in several instances. For most of us, though, there is already an abundant and complete music present in the poems themselves, if we never hear them sung. Neilson begins to be known through Dr. Whittaker, through A. G. Stephens, and through other less articulate but constant lovers. Still, it is inconceivable that he should ever be a "popular" poet, like "Banjo" Paterson, for instance. Yet popularity is taken as a standard of excellence! Our hearts may leap to the warm, human feeling that throbs through Paterson's ringing verse; yet we feel that Shaw Neilson's shy muse has her finger nearer to the central pulse of the world. We can see why several people, knowing Shaw Neilson's songs and brooding over them, would in all sincerity write him down as one of our greatest and purest singers.

"The Heart of Spring" is out of print; so, I think, is its successor, "Ballad and Lyrical Poems," published in 1923. While waiting for a new edition of these, we can content ourselves, very soon, with a volume that has just been announced as due in November. "New Poems," by Shaw Neilson, will contain a large group of poems written against all odds, during the last three years. Quietly, slowly, the work of Shaw Neilson is becoming known, its sweetness permeating our literature with its own contribution of individual fragrance:

It is the white plum-tree,First published in The Brisbane Courier, 29 October 1927

[Thanks to the National Library of Australia's newspaper digitisation project for this piece.]

|

When Colts Ran Roger McDonald Random House 2010 |

In this sweeping epic of friendship, toil, hope and failed promise, multi-award-winning author Roger McDonald follows the story of Kingsley Colts as he chases the ghost of himself through the decades, and in and out of the lives and affections of the citizens of 'The Isabel', a slice of Australia scattered with prospectors, artists, no-hopers and visionaries. Against this spacious backdrop of sheep stations, timeless landscapes and the Five Alls pub, men play out their fates, conduct their rivalries and hope for the best.

Major Dunc Buckler, 'misplaced genius and authentic ratbag', scours the country for machinery in a World War that will never find him. Wayne Hovell, slave to 'moral duty', carries the physical and emotional scars of Colts's early rebellion, but also finds himself the keeper of his redemption. Normie Powell, son of a rugby-playing minister, finds his own mysticism as a naturalist, while warm-hearted stock dealer Alan Hooke longs for understanding in a house full of women. They are men shaped by the obligations and expectations of a previous generation, all striving to define themselves in their own language, on their own terms.

When Colts Ran, written in Roger McDonald's rich and piercingly observant style, in turns humorous and hard-bitten, charts the ebb and flow of human fortune, and our fraught desire to leave an indelible mark on society and those closest to us. It shows how loyalties shape us in the most unexpected ways. It is the story of how men 'strike at beauty' as they fall to the earth.

Reviews

James Ley in "The Age": "Roger McDonald has long been interested in aspects of the national experience that have taken on iconic significance. His writing depicts an Australia defined by convicts and Anzacs, by its vast outback stations and shearing sheds...That these elements of the nation's cultural identity have been romanticised and mythologised to the point of cliche is not lost on him. The jokily derisive references in When Colts Ran to that virtuoso of the rural potboiler, Ion Idriess, are testament to that. But for McDonald the challenge in tackling subjects that evoke certain nationalistic stereotypes is to render them with the kind of complexity and literary sophistication they are often denied -- as if Idriess, instead of punching out a new book every nine months or so, had brought to his task a deeper sense of purpose and a poetic sensibility capable of sculpting sentences with Faulknerian precision...When Colts Ran offers a vision that is ultimately tragic, not in any strictly formal sense, but in its positioning of the travails of individual lives within a larger determining context whose shape and influence is only evident in retrospect."

Geordie Williamson in "The Australian": "There has always been something of the 18th century about the fiction of Roger McDonald, who won the Miles Franklin in 2006 for The Ballad of Desmond Kale. When Colts Ran shares with his earlier novels a vibrancy, expansiveness and love of the picaresque. It, too, is concerned with a largely homosocial world, country Australia in the postwar era being one of the few places where the Regency swagger of the Anglo past could be replicated without seeming absurd...McDonald's use of different-angled lens throughout makes for a complex and ambitious work. On one hand, the author seeks to join the Australian novel with a form inaugurated 2500 years ago in classical Greece and brought to a fresh perfection in our language by Shakespeare two millenniums later; on the other, he is attempting to conflate a national type with an individual."

Patricia Maunder on "The Book Show": "It's no surprise that Roger McDonald's latest novel began as a series of unrelated short stories about boys and men struggling to understand their purpose in life. A chapter or two of When Colts Ran is dedicated to one character, then he may disappear for a couple of hundred pages. Later, his mate or his son might take centre stage for a while. The links that hold them together -- friendships, affairs, blood relations, chance -- are complex. Sometimes they're disturbingly oblique, stretching to breaking point from one apparently minor episode, to something quite profound many pages and years later...Ultimately, When Colts Ran is a subtle debate between the material and the spiritual, the real and inner worlds of its menfolk. This is epitomised by what McDonald describes as the 'desperation landscape' that is so important to the story. It's both the source and inhibitor of income, and the means to either inspire or crush men's souls. The fact that all of them want to leave their mark on mighty and capricious Mother Nature -- to subdue, exploit or understand her -- hints at why their lives are so tragically wasted."

Lisa Hill on "ANZ LitLovers" Blog: "This is a fine book that has important things to say about gender identity in Australia, not just in the bush but in society in general. It debunks myth-making about rural life with a sobering picture of a sense of disarray. It reminds Australians that we need to re-evaluate and support rural life for it to thrive...It's also very good fun to read!"

Interview

"Booktopia" blog

Other

Roger McDonald with notes on aspects of the novel.

Roger McDonald on YouTube discussing the novel:

|

Craig Sherborne is best known for his two volumes of autobiography, Hoi Polloi (2005) and Muck (2007), but has now produced his first novel, The Amateur Science of Love, which has just been published by Text. He recently spoke to Liza Power from "The Age": |

After the death of his close friend, the great poet Peter Porter, last year, Sherborne wrote a tribute. He began: ''[Poetry] wasn't just some media voice reducing human experience to sound bites and headlines. It was the highest application of language. It was the most resonant chiming of music and meaning: 'I play the sad music my conscience urges.' ''

Fittingly, then, The Amateur Science of Love began as a poem. Titled Showing, it painted the portrait of a mastectomy patient, Sherborne's then lover, and was written when its author was in his late 20s. Later published in his collection titled Bullion in 1995, it was a turning point.

''It was the first decent poem I'd ever written,'' he says. ''I hadn't really written anything I'd liked much, apart from a play for Radio National. It was difficult subject matter but I felt I'd suddenly found my voice: the tone, structure, simplicity, unpretentiousness. [Writing it] felt like finding my purpose in life.''

Its second beginning, a short story titled Unforgiven, was published in The Monthly in 2008. Like its later incarnation as a novel, it's a love story and while it begins ''To be unforgiven is no great shame'', both tales unfurl in a way that suggests otherwise.

''The idea that got the book started was this person trying to redeem himself, sitting down to write a testament. He's failed the relationship [he's in] but he can't ask for forgiveness because the only person he can ask has died. He has to redeem himself to himself. And maybe that's just making excuses but it's crucial to his survival. Unless he does it, he's less than half a human being.''

It isn't. One would say it cannot be; were it not that poetry still here and there succeeds in swathing the most unpoetical words with an atmosphere of beauty; like the moss that (with time and moisture and a little soil) will even grow on a rusty old kerosene tin.

But poetry is a daughter of music; and there are discords in which music, with the best will and the finest instrument, becomes only noise. Many words, such as kitchen, quagmire, wattle, make a discord in poetical language.

Wattle is worse, because it makes a specious appeal to the popular poetical device of rhyme. Many of our early swagmen have died poetically beneath a wattle -- which, as far as my knowledge extends, is one of the last trees a swagman would choose to die under; if a choice were given him.

But the association between the view obvious wattle and the appropriate rhyme of "bottle" is clear; and there is the easy rhyme of "throttle." So the early poet meditated; and the poem leaves his throttle like a blessing from the bottle that consoles the weary swagman as he dies beneath the wattle.

Later poets dare not write so; though some of them apparently would like to: but civilisation has marched; and they dimly feel that those rhymes are below their dignity. Yet -- "cottle," "glottal," "pottle," "tattle," "twattle," -- what else? An excellent but desperate poetess has tried "mottle"--

All noon, where the noon-lights mottle,It is not happy.

Other poetesses have discreetly dodged the rhyme:

"Why should not wattle doAnd the poetical maiden answered prettily:

"Since it is here, and you,Much can be done with "wattle bloom" and "wattle-blossom" to soften the gurgling, choking sound that naturally reminded the pioneers of a death-rattle. One of the best wattle poems uses an effective refrain, "when wattles bloom":

When wattles bloom the airs are sweet with Spring:And the sound can be smothered in a wave of emotion:

The golden eve is round me now,Kendall's sensitive ear rejected wattle for "mimosa," a literary use now rare, once not uncommon:

The low mimosa droops with locksOur "wattle," indeed, is now the world's "mimosa." Beyond Australia you hear only of wattle-bark, many years exported for tanning leather. "Mimosa" -- Australian mimosa acclimatised, with its source long forgotten -- floods Southern France and Italy, and burgeons in North Africa. Mimosa has sent the Americas, North and South, into raptures; it is even ostracised as too popular. Says a writer in "The Bookman," New York, for June last:

"The outstanding feature in the drama of the past season has been the elimination of mimosa as piano decoration. Ever since 1922 our entire dramatic scheme has been dominated by this yellow blossom. But in the fall of 1928 the managers took the matter into their own hands. Mimosa was out."

Our name "wattle" is good old English applied by Governor Phillip's first makers of "wattle-and-daub" huts; interlacing and covering with clay the flexible branches of the wattle. Its utilitarian meaning is to twist or plait; without reference to the golden blossoms that never grew in England, to "wartle" like the warts on the neck of a turkey-gobbler.

For poetical purposes, mimosa is preferred; and already many mimosa poems have been written in the United States; where our wattle-blossom is being absorbed as a national flower, as our eucalyptus has been annexed as a national tree. It is conceivable that, at some distant day, there may even be more mimosa blooms beyond Australia than there are wattle blooms within Australia. Meanwhile, with their national treasury of scented gold, Wattle Days dawn anew.

First published in The Brisbane Courier, 10 August 1929

[Thanks to the National Library of Australia's newspaper digitisation project for this piece.]

|

Bereft Chris Womersley Scribe Publications 2010 |

[This novel has been shortlisted for the 2011 MIles Franklin Award.]

From the publisher's page:

It is 1919. The Great War has ended, but the Spanish flu epidemic is raging across Australia. Schools are closed, state borders are guarded by armed men, and train travel is severely restricted. There are rumours it is the end of the world.

In the NSW town of Flint, Quinn Walker returns to the home he fled ten years earlier when he was accused of an unspeakable crime. Aware that his father and uncle would surely hang him, Quinn hides in the hills surrounding Flint. There, he meets the orphan Sadie Fox -- a mysterious young girl who seems to know more about the crime than she should.

A searing gothic novel of love, longing and justice, Bereft is about the suffering endured by those who go to war and those who are forever left behind.

Reviews

Peter Pierce in "The Sydney Morning Herald": "After the critical acclaim for The Low Road (2007), his first novel about two desperates on the run, Chris Womersley was evidently undeterred by the hurdle of its successor. Bereft is a bleak and brilliant performance that confirms him as one of the unrepentantly daring and original talents in the landscape of Australian fiction. (And there is no clank of the creative-writing production line about him.)...Few recent novels, Australian or otherwise, have such eloquence, prompted by the despair of sufferers who do not shirk the task of seeking the right words...The last part of Bereft is frightening in a way that reminds one of why several reviewers of Womersley's first novel made comparisons with Cormac McCarthy. In the novel's bloody climax, the Angel of Death appears to torment one of the guilty. Other characters vanish into a fog of rumour. The most chilling words of Bereft are reserved until the last page. This is an outstanding work of Australian fiction. Read it next."

Jennifer Levasseur in "The Age": "The Low Road, winner of the Ned Kelly award for best first book, examines the anguish of lives gone hopelessly wrong, of men pushed beyond what they felt were the limits of their capabilities. Bereft, Womersley's new novel, is a strong, more compelling follow-up that explores some similar themes but urges them to new depths...Beautifully written and conceived, Bereft pushes at the borders of literary fiction and thriller, spinning a horrific incident in one man's life into a page-turning reflection on grief and guilt, on the nature of storytelling and its inevitable joys and shortcomings, on what we have to believe in order to survive."

Geordie Williamson in "the Australian": "It must have been some expression on Chris Womersley's face after the eureka moment when Bereft was born...First, excitement at the potential of setting an Australian gothic novel in the immediate aftermath of World War I, during the influenza epidemic that turned rural Australia into a patchwork of plague villages; then, anxiety that someone else might write it first. I would have hugged the manuscript to my person like Gollum's ring...Now he has relinquished the story, it's worth noting that Bereft represents an elaboration of those attitudes and concerns that made his 2008 debut, The Low Road, so gripping, such a cut above the usual genre fare. It is a whodunit that yields up its secret halfway through: a murder mystery from an era when death undid so many that the worst crime became a dreary norm. The novel's historical moment activates a nihilism that settles, like the mustard gas which has ruined its hero, over everything and everyone."

Lucy Clark in "The Courier-Mail": "Womersley combines really beautiful and eloquent writing with a compelling story, and Bereft has a literary sensibility flavoured with the drama of a mystery...His characters are gently but thoroughly drawn, with Quinn Walker reflecting on his defining experiences at war - these scenes are bloody and visceral - and in particular his experience at a seance where he may or may not have been contacted by the spirit of his beloved sister...Bereft is a haunting and beautiful novel that will surely deliver an excellent Australian writer to a much wider audience."

Thuy Lunh Nguyen in "Kill Your Darlings": "Bereft's imagery is also softer than its predecessor's. In The Low Road, Womersley evokes characters and settings by building upon our familiarity with the modern city...On the other hand, Bereft must work with weaker foundations - second-hand accounts of events beyond living memory; hence, Womersley's sketches leave only an impression of an era, a nation's mood - nothing concrete. Nevertheless, his early twentieth century New South Wales is a convincing one, thanks to his characters, who exhibit a healthy respect for both the scientific and the arcane: Quinn's father is enamoured by electricity and aeroplanes and yet swears he has seen a yowie. These individuals make up a society that knows how to build tanks but also has a real fear of dead men walking and Armageddon...The townsfolk's superstitions combined with supernatural happenings mark Bereft as a historical novel with gothic sensibilities."

Angela Meyer in "Bookseller+Publisher": "Chris Womersley's Bereft, his second novel after 2008's award-winning The Low Road, is a rich, gripping tale of love, loss, conflict and salvation....This book is thoroughly enjoyable, compelling, moving, warm and completely memorable. I had that very rare experience of wanting to read it again, almost immediately. This book crosses the lines of popular fiction, literary fiction and mystery."

Sam Cooney on "Readings Bookshop" website: "Like all great literary fiction, Bereft aspires to go beneath the surface, beyond flimsy payoffs and superficial triumphs. In doing so it confronts such pillars as loss, longing and revenge, and sears itself into memory."

Interviews

Peter Mares on "The Book Show".

Booktopia blog

All the World's Our Page blog

Other

The author himself has a webpage devoted to this book.

Book Trailer

Daley met Farrell in Queanbeyan a quarter of a century ago. Farrell was then engaged on the unpoetical work of brewing beer -- later, when he wrote poetry and leading articles, he used to say "the more congenial work." Victor Daley, a young, fresh-blooded Irishman, walked into Queanbeyan one day, and got a job on the "Times'' of that town, then owned by Mr. John A. O''Neill. He went to live with O'Neill, who soon recognised he had made a good bargain, for Daley's work made the "'Times" a new paper, and people bought it because of its cleverness and its novel features. Farrell and Daley both put a lot of their early verse into it, and many a fine joke they used to tell about those days afterwards. One of them is worth narrating. The town had just been incorporated, and the numicipal elections were approaching. The temperance people banded themselves together. Farrell (the brewer!) went to O'Neill. "We'll have to fight these good temperance folk," he said with his fine, rich, Irish brogue. And O'Neill told him he could use his paper in ''the cause of fairplay." There was a meeting one night in opposition to the temperance party, and one man in the audience kept making interjectings. "Who is the man who is interjecting ?" it was demanded from the platform. "The man who will be Mayor," came the reply. And the man's name was Nathan Moses Lazarus. That week Farrell wrote these hitherto unquoted lines for the Queanbeyan "Times":-

There is Irish humor in this skit, and it seems to have had its effect,for Lazarus, though he made a very estimable alderman, was not elected Mayor. For a time Farrell and Daley contented themselves with writing jingle like this. One day a deaf and dumb comp. named Jordan drew on the whitewashed plaster above the fire a picture intended to represent a little angel of about seven summers banging a drum. Daley wrote these lines below it:-

Lord, give me in the realms of blissFancy Daley ever having written such a word as "measly." But these are types of early efforts of twin souls ere they had more fully cultivated the Muses. Besides, Daley drew a thick line between poetry and verse. "Write us some poetry, Mr. Daley," said one of the comps. on one occasion, pointing to the drum and angel. "That's not poetry, my boy; that's verse," said Daley.

As some one has already pointed out, Queanbeyan 20 years ago was what might aptly be described as a Mecca for literary pilgrims. Why ? O'Neill. His heart was so big and he was doing so worldly well that any man fallen on evil days -- especially if he were Irish -- could be sure of his lending a helping hand. Moreover, it is just within the bounds of possibility that those who had tasted of his hospitality used to '"pass the word on," as tramps are said to do, and it was no uncommon thing for minor poets to travel down from Sydney tired of Riot, to take refuge at this Writers' Rest. Several names recur to me, but they don't concern us now. Daley, Farrell, and others who were making their way up the literary ladder, were oftentimes found smoking their pipes together in Queanbeyan. The two I have named were practically fast friends for life. Practically starting out together, it is curious how they stuck to each other. I remember a good many years ago buying a copy of the "'Bulletin'" book with the tltle of "The Golden Shanty." There I found Farell and Daley side by side. I haven't the book by me now, but I remember Farrell's "How He Died" and "The Last Bullet" were there. I forget Daley's verse. Long before that Daley had published many verses -- some in Melbourne, some in Sydney. His first contribution to a Sydney paper was, I believe, "The stucco age," which appeared in old Sydney "Punch." It began--

This is the stucco age, the age of sham:In later years Daley and Farrell saw much of each other in Sydney. The former used to tell of a visit he paid to Farrell one night in the "Daily Telegraph" office. ''Which of us is going to write an obituary notice of the other?" asked J. F. They spun a coin. Heads, Daley wrote; tails, Far- rell. "The coin ran under the table,'' said Daley, a few days after his friend's death, "and I think Courtney found it afterwards, but it must have been heads." Daley wrote the obituary, and among other things he wrote was this: - "I remember quoting to him on an evening the saying of Abou ben Zeeyd -- 'I am a singing man of the singers -- the world's guest and a stranger.' He said he would say it about me. And I have to say it about him."'

Yet neither of them is a stranger. Both men have gone, but they live for us still in their work. When they buried Daley on Saturday they took with them to the grave a beautiful floral harp, with a laurel wreath attached, and a heart of red carnations and bonvardia -- and a streamer said."Victor -- in verse, in life, in song." This from "some lovers of Victor Daley and some admirers of Australian verse." There were many at the graveside, and though some may never have met him, he was no stranger. Rather was he "singing man of the singers -- our guest and familiar friend!"

First published in the Sunday Times (Perth), 28 January 1906

Note: Victor Daley (1858-1905) died on 5 December 1905. John Farrell (1851-1904) died on 8 January 1904.

You can read the full text of The Golden Shanty, the anthology mentioned above, care of Austlit.

[Thanks to the National Library of Australia's newspaper digitisation project for this piece.]

It would seem that Victor Daley, known until lately to but a comparatively few literary students, has by his lamented death bred quite an army of adulators, who either knew him, ate with him, got into a state of paralytic intoxication in his company, or never knew him at all, but still pretend to have done. The grief of those who were really friends of Daley is not likely to prompt them to use their acquaintaince with the Australian poet for advertising purposes; but among the army of adulators there seems to be a sufficiency of those who desire to slobber over a dead man's verses and his past -- to claim, as it were, a part of the poet's fame for themselves and warm themselves in a ray or two of the sun which has risen over the dead man's grave.

The latest comment through the columns of a much-read weekly is that "Vic." (which contraction of the poet's Christian name discloses how intimate must the writer of the worship-wash have been with the poet!) once handed the writer of the article some of his MS.S., and he (the writer of the article, not of the poem), on perusing it, "immediately fell down and worshipped." It is probable that, as usual, the public of Australia will be pelted with such pebbles of reminiscence on Daley for months to come.

First published in the Barrier Miner, 30 January 1906.

Note: Victor Daley died on 5 December 1905.

[Thanks to the National Library of Australia's newspaper digitisation project for this piece.]