March 2010 Archives

Mary Hannay Foott is described in the Australian Dictionary of Biography as "a minor poet", though I suspect this is manily due to the relaively small number of poems she published during her lifetime: Austlit lists only 76. Most of these works appeared in various Queensland newspapers with the odd one or two in The Bulletin. So it was probably more a matter of her lack of exposure rather than anything else. She only published two collections of poems during here lifetime, Where the Pelican Builds and Other Poems in 1885 and Morna Lee and Other Poems in 1890, and wrote very little after the mid-1890s.

I quite like this poem. It is short but gives a good sense of the interplay between nature and men's fortunes - straddling the gap between Charles Harpur and Mary Gilmore perhaps, as there appear to be echoes of both in this work. Where the pelican builds its nest is considered the best country, fertile and well-watered. They prefer large expanses of open water without too much aquatic vegetation which provides perfect breeding conditions for fish, their main source of food. More pelicans implies more fish, which implies more clean water and a better natural environment.

Mary Hannay Foott wrote this poem while she was living in south-west Queensland, an area of the country prone to the classic "droughts and flooding rains". When the pelican arrived in the area everyone would have been acutely aware that good times had returned, and you are left in no doubt that this is what is indicated in this work.

Text: "Where the Pelican Builds" by Mary Hannay Foott

Author bio: Australian Dictionary of Biography

Publishing history: First published in The Bulletin (12 March 1881), and subsequently reprinted in An Anthology of Australian Verse (1907), The Golden Treasury of Australian Verse (1909), Australian Bush Songs and Ballads (1944), Silence Into Song (1968), A Treasury of Australian Poetry (1982), The Macmillan Anthology of Australian Literature (1990), The Penguin Book of Australian Ballads (1993), The Oxford Book of Australian Women's Verse (1995), Classic Australian Verse (2001) and Our Country: Classic Australian Poetry: From Colonial Ballads to Paterson & Lawson (2004).

Next five poems in the book:

"Narcissus and Some Tadpoles" by Victor Daley

"Nine Miles from Gundagai" by Jack Moses

"The Duke of Buccleuch" by JA Philp

"How We Drove the Trotter" by W. T. Goodge

A. G. STEPHENS.

Sir, - As the second anniversary of the death of A. G. Stephens approaches, those interested in Australian literature would like to see some memorial to this outstanding Australian, Joseph Furphy, with whom the name of Stephens is for all time associated has been recently remembered by a tablet. Something of the kind might be erected by subscription to Furphy's contemporary. A. G. Stephens is admittedly our most notable critic. He was independent, percipient, original, witty, and had a true perspective of the relation of Australian literature to its parent stores, as well as vision and enthusiasm regarding its indigenous importance and achievement. His credo for critics is expressed in a passage in his last booklet, "Chris Brennan": - "When a critic denies or delays due praise of good work, or due blame of bad work, because an author is not or is a blood-brother or a sodality-member, then his justice is clouded, his arc is tarnished, and his criticism is shamed."

I am, etc.,

Sydney, April 3. MILES FRANKLIN.

First published in The Sydney Morning Herald, 22 April 1935

[Thanks to the National Library of Australia's newspaper digitisation project for this piece.]

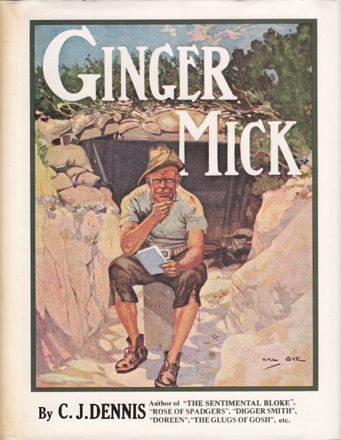

The Moods of Ginger Mick by C. J. Dennis, 1916

Cover illustration by Hal Gye

Angus and Robertson edition 1982

|

Sons of the Rumour David Foster Pan Macmillan 2009 |

[This novel has been longlisted for the 2010 Miles Franklin Award.]

From the publisher's page

Sons of the Rumour is nothing short of a dazzling and genre-defying work of genius. Foster retells the tale of the legendary eighth-century King Shahrban of Persia who, furious at his wife's infidelity, has decided to marry and then behead a fresh virgin every day. But then the king meets Scheherazade, a beauty of such wiles and storytelling gifts she manages to entertain the him for 1001 nights, staving off death for both herself and her countrywomen. In the process, she also bears him three sons, wisely educates him in morality and kindness, and eventually convinces him to take her as his lawful wife.

Intersecting with the historical tale is the story of Al Morrisey - a middle-aged, Anglo-Irish, former jazz-drumming everyman, on the run from a failed marriage, and cursed with Freudian daydreams of his mother and peculiar nightmares of all things Persian - as he vainly attempts to reconcile the past with the present and reclaim some of his youthful vigour.

Ingeniously manipulating the frame tale of the Arabian Nights, and utilising all his narrative gifts of adventurous satire, David Foster has produced a work of fiction like no other. Sprawling, ambitious, explicit but frequently hilarious, Sons of the Rumour is a modern masterpiece, an utterly original novel by one of Australia's greatest living writers, a man who the Sydney Morning Herald critic Andrew Riemer has called Patrick White's worthy successor.

Reviews

Susan Lever in "The Australian": "This is certainly fiction, but it is hardly what most readers consider a novel. It may recall Rushdie's Satanic Verses with its modern take on ancient texts, but Sons of the Rumour values stories as the means of understanding the mysteries. Foster adopts the premodern form of the literary anatomy to range over a mass of disparate stories, opinions, learning and vulgarity as he digs deep into the philosophical origins of sexual and religious behaviour...The book may be read as a form of spiritual exercise for author and reader, an inquiry into the possibilities for spirituality for unbelievers, when atheism has become a rallying point. It is also an entertaining tour de force by a writer in mature command of language. It is Foster at his very best, overwhelming the reader with his imagination, comic energy, wisdom and the richness of his material."

James Ley in "Australian Book Review": "Sons of the Rumour, Foster's fourteenth novel, is his most substantial and brilliant work since The Glade within the Grove (1996). A roiling, historical, pantheological satre, it is alos very much an extension of the themes that have driven his remarkable fiction for more than four decades. The novel is explicity concerned with the interaction between the 'Two Worlds' of spirit and flesh. It deploys Foster's formidable erudition to this end, quoting from a dizzying aray of religious texts from a host of different traditons. The many stories it contains anatomise, in a comical and sometimes brutal fashion, the ways in which sexual desire and religious belief inform and distort each other...Attempt to characterise Foster's writing and eventually one will run out of adjectives. There is simply no one remotely like him in contemporary Australian fiction. He is so far ahead of anyone else that t's not funny. Except that it is funny -- very, very funny."

Short notice

Anna Hedigan on ABC Radio National's "The Book Show": "Transformation is the point to which everything returns in Sons of the Rumour -- the great work of finding meaning in life and the inner purity required to achieve it. I wished for a bit less testosterone and a more discerning rigour in the philosophical inquiry, but Foster rarely disappoints with his ambitious and unique style."

Interview

Paul Sheehan in "The Age".

Other

You can read an extract from the novel on the publisher's page [PDF file].

I.

Lady, I would this little gift

Should tell in years to come of me,

And on thy failing memory lift,

A thought of one who honors thee.

II.

I never read a favorite book,

If read by one, my youth has known,

But it recalls the tone, the look,

That dwelt with them, tho' years have flown.

III.

The simple mark, their pencil traced,

Recalls some cherished thought or word --

A feeling -- not to be effaced

By aught the heart may since have heard.

IV.

Then let this little work possess

That silent, but endearing spell,

Which in thy hours of happiness,

A something still of me may tell.

First published in The Sydney Herald, 13 March 1834

The winners in the South East Asia and Pacific Region were:

Best Book

The Adventures of Vela by Albert Vendt (Samoa)

Best First Book

Siddon Rock by Glenda Guest (Australia)

That's probably the first win by a writer from Samoa in any category, and given the winner was up against Carey and Coetzee, amongst others, it must have a fair bit going for it.

The overall winners in each category, that is the best from all regions, will be announced in Delhi on April 12.

A Shearer Violinist

It is not usual to associate Henry Lawson with the musical art, his works being more reminiscent of the cracking of stockwhips, and the creak of the mining windlass. Having Gipsy blood in his veins, however, it is not surprising to find that he was profoundly affected by melody and harmony. Exotic music of the studio did not appeal to him, nor the cheap tunes of revue and musical comedy: he preferred the old folk songs, sung and played around camp fires. In mining camps, on outback farms, and wherever pioneers and adventurers gather.

Of all musical instruments Lawson preferred the violin - his Gipsy blood would account for that, the violin being the instrument of the wanderer. I have the good fortune to be possessed of a violin that formerly belonged to one of Lawson's mates. On the back of it is inscribed "To my mate, Perce Cowan and his violin, with gratitude for light in dark hours - Henry Lawson." Cowan was a shearer, and, many years ago, he and Lawson were often together "on the wallaby." When the war broke out, Cowan enlisted, and went to the front. After the Armistice he returned, and, in Sydney, renewed his friendship with Lawson. Another returned soldier who was a close friend of both Lawson and Cowan is Douglas Grant, a highly educated Queensland aborigine. Douglas is the only one of the three now living. On being shown the violin he greeted it as an old friend, and told how he and Cowan, with the violin, used to go over to where Lawson lived in North Sydney, when Cowan would play, while Lawson sat at the table and wrote. With tears in his eyes, Douglas vividly described the little room, even going into such details as an old newspaper being spread on the table in lieu of a cloth.

Charming a Snake

Some time back In the 'nineties, Lawson wrote a short story on an incident that occurred when he and Cowan were "on the track." Although I searched through the back numbers of papers and journals in which his works were usually published, I could not find the story, but its salient points were related to me by one who had read it. As far as he could recollect, it was as follows:

Lawson and Cowan were carrying their swags out Cobar way, when, as evening came on, they met a couple of men, also on the tramp, who informed them that there was a deserted hut not far ahead, but warned them not to camp there, as a snake had made its home under the flooring. When the mates reached the hut, they agreed that it would be just the place in which to spend the night if it were not for the snake, so they decided to try and kill it. But how? The usual bush method of enticing it out by placing a saucer of milk near its home was not practicable, owing to the simple fact that they had no milk. At last Lawson had a great idea. He told Cowan to get his violin, and charm the snake out. Cowan unpacked his violin, rosined his bow, and struck up "Annie Laurie," while Lawson, armed with a stick, stood by ready to despatch the reptile if it put its head out. Whether the snake was lured out In this way my informant could not remember, but I hope some day to read the conclusion of the yarn in some old newspaper file.

The monument to Lawson in the Outer Domain is a monument also to the spirit of Australia as portrayed by literature. Unfortunately, the sister art of music has not developed in a similar national manner, unless the swagman's song, "Waltzing Matilda." could be claimed as such. Now, however, that the flood of imported sentimental songs and jazz is declining, there is a chance of something expressing the true soul of the country arising from where all such music comes - from the people of the soil and the open spaces.

First published in The Sydney Morning Herald, 1 August 1931

[Thanks to the National Library of Australia's newspaper digitisation project for this piece.]

|

Parrot and Olivier in America Peter Carey Penguin Books 2009 |

[This novel has been shortlisted for the 2010 Commonwealth Writers' Prize in the South East Asia and Pacific region, and longlisted for the 2010 Miles Franklin Award.]

From the publisher's page

Olivier is a young aristocrat, one of an endangered species born in France just after the Revolution. Parrot, the son of an itinerant English printer, wanted to be an artist but has ended up in middle age as a servant.

When Olivier sets sail for the New World - ostensibly to study its prisons, but in reality to avoid yet another revolution - Parrot is sent with him, as spy, protector, foe and foil. Through their adventures with women and money, incarceration and democracy, writing and painting, they make an unlikely pair. But where better for unlikely things to flourish than in the glorious, brand-new experiment, America?

A dazzlingly inventive reimagining of Alexis de Tocqueville's famous journey, Parrot and Olivier in America brilliantly evokes the Old World colliding with the New. Above all, it is a wildly funny, tender portrait of two men who come to form an almost impossible friendship, and a completely improbable work of art.

Reviews

James Bradley in "The Australian" : "...Parrot and Olivier in America manages to marry the urgency of Theft to the precision of Carey's earlier fiction. The result is a book that in its best moments achieves a sort of rackety joyousness...Nonetheless, it would be a mistake to confuse the book's sprawl or occasional lack of focus with a lack of control...Because for all that it is a book that often seems most alive when at its wildest and most inventive, it is also a book keenly aware of the ironies and contradictions at its centre...Carey may be a republican, and a passionate believer in the possibilities of Australia and Australian culture, but the spirit of his fiction is too restless, too contrarian to have much truck with the sentimental pieties of Australian nationalism. Like Kate Kelly in True History of the Kelly Gang dismissing Ned's and Joe's stories about the brave fight against the English back in Ireland as sentimental nonsense about brutal murderers, Carey's fiction repeatedly evinces a profound ambivalence about the self-deceptions of colonial culture, about the dishonesty at its core, and its celebration of its mediocrities as virtues."

Andrew Reimer in "The Sydney Morning Herald": "Parrot and Olivier in America sounds like the title of a children's book, and there is indeed something irresistibly youthful about the zing and bounce of this picaresque tale spanning three continents. This is Peter Carey at his best: playful, extravagant, even rambling at times, yet fully in control. It is sometimes hard to know where these adventures are heading, yet they all finish up going somewhere meaningful and satisfying...Parrot and Olivier in America is a tour de force, a wonderfully dizzying succession of adventures and vivid, at times caricatured, characters executed with great panache. Telling this intricate story is shared by Olivier and Parrot in alternate chapters, a clumsy device in some hands but highly successful in Carey's."

Ursula K. Le Guin in "The Guardian": "..exactly as its title promises, the book is about Parrot and Olivier in America; but it's not about America. Its picture of the coarse, young United States of Andrew Jackson - based largely on De Tocqueville, of course, and I think also on later observers such as Frances Trollope and Charles Dickens - is entertaining, if predictable...The narrative proceeds in leaps and bounds, sometimes with a hop backwards, omitting connections, giving an impression above all, perhaps, of confusion - confusion of event and motive, incomprehension, a vast drama without structure. The language is vivid, forceful and poetic (though I wish Olivier's aristocratic locution was free of grammatical blunders such as 'of she toward whom', 'of she who I affected to be unaware of', 'to he who I intended to make my father-in-law'). There are terrific set pieces, such as the burning of the forgers' house - moments Dickensian in their vividness. Themes of fire and burning run through the story. An early kind of bicycle appears, with much discussion and even an illustration, and later on an American bicycle enters the tale. Are there hidden significances? I don't know. It's a dazzling, entertaining novel. Should one ask for more?"

John Preston in "The Telegraph": "There are certain things you know you're going to get from a Peter Carey novel: scale of ambition, narrative boldness, apparently inexhaustible imagination and fizzingly exuberant imagery. Even by his standards Carey's 11th novel, Parrot and Olivier in America, has all these in abundance...Like Carey's 2001 Man Booker Prize-winner, True History of the Kelly Gang, Parrot and Olivier in America has an epic historical sweep to it. Yet for all the novel's virtues, the book can't muster the same emotional impact as its predecessor. In part, this is due to the nature of the story. However, there are other factors, too. The friendship between the two men comes to feel increasingly contrived. Sparring away with one another, Parrot and Olivier work wonderfully well, but once they've buried their differences, they tend to lose definition as well as edge."

Philip Hensher in "The Monthly": "Parrot and Olivier is in many ways beautifully done; it is written with all its author's celebrated mastery of style; it is organised very neatly around sets of ideas, including original and reproduction, master and servant; it has the surface appearance of great energy. But nothing human in it much engaged me, and I found myself reading on for the pleasure of the sentences only. It amounts to an exquisite divertissement but, as the book goes on, the suspicion grows that the author is diverting himself much more than the reader. After all, divertissements were written in Carey's chosen period with the full intention that the audience would carry on conversations simultaneously, relegating the artistic invention to the background of their attention."

Andrew Taylor in "The Independent": "Carey's novel builds a picture of America, his own adopted homeland, seen through a glass darkly from a fictional version of the 1830s. Its mainspring is the dialogue that develops between Parrot and Olivier. Parrot is pragmatic, a natural republican, and resourceful. Olivier, a faintly ridiculous child of the ancien regime, judges what he sees and whom he meets by aristocratic and European criteria; and yet is too intelligent, and in some ways too generous, not to ignore the virtues of both this brash, alien country and his irredeemably vulgar fellow traveller...This is one of the strongest points of the novel: the reader never quite loses sympathy with Parrot or Olivier. Another of its virtues is Carey's wonderfully witty and visual prose, which springs surprise after surprise on the reader. A third is that his version of 1830s America allows him to comment on its modern counterpart: he touches lightly on, among many other things, sub-prime mortgages, an inflated art market and demagogic politicians. "

Short Notices

Mark Rubbo of "Readings": "In this marvellous book, Carey will no doubt antagonise and provoke some critics: firstly for his departure from an Australian theme and secondly for his unabashed admiration for the principles of the American democratic tradition. In spite (or because) of this, it is a grand, magisterial story, full of great characters and stories. Above all, it is one of his most important books and a major development in his writing career."

Chris Flynn on the "Falcom vs. Monkey" weblog: "Parrot and Olivier in America is one of Peter Carey's finest achievements, elevating him far above the rest of literature's maddening crowd. There's even a nod to the Aussies in the form of a devilishly funny early map of the colony. The man deserves his head on a stamp."

Interviews

Carey is interviewed by John Freedman of "Granta" magazine about the book.

Tom Leonard in "The Telegraph".

Brian Appleyard in "The Times".

Rosanna Greenstreet in "The Guardian".

Ramona Kaval on ABC Radio National's "The Book Show".

"The Thought Fox", the Faber publishing house weblog.

Other

Carey discusses the novel on Penguin TV, via YouTube.

The UK and US covers of the novel are as follows:

|  |

| UK cover | US cover |

The longlist is:

Figurehead, Patrick Allington (Black Inc. Publishing)

Parrot and Olivier in America, Peter Carey (Penguin Group)

The Bath Fugues, Brian Castro (Giramondo Publishing)

Boy on a Wire, John Doust (Fremantle Press)

The Book of Emmett, Deborah Forster (Random House)

Sons of the Rumour, David Foster (Pan Macmillan)

Siddon Rock, Glenda Guest (Random House)

Butterfly, Sonya Hartnett (Penguin Group)

The People's Train, Tom Keneally (Random House)

Lovesong, Alex Miller (Allen & Unwin)

Jasper Jones, Craig Silvey (Allen & Unwin)

Truth, Peter Temple (Text Publishing)

The shorlisted works will be anounced in April, and the winner on June 22.

A total of 50 novels were submitted for this year's award, and, as usual, there are some notable omissions from this list.

James Bradley appears to be the first cab off the rank with a discussion, and he mentions the omission of The World Beneath by Cate Kennedy, Things We Didn't See Coming by Steven Amsterdam, and The Danger Game by Kalinda Ashton.

The reviews of the Kennedy novel certainly pointed to some level of recognition on this award. The Amsterdam I thought was very good, but if it is set in Australia at all it doesn't make that overly explicit. The judges probably thought it too generic as to locale to fit the award's criteria of "portraying Australian life in any of its phases." A point that James makes regarding the inclusion of Carey's "American" novel; a book with little connection to Australia.

Oh, isn't it good to have an award longlist to slag off about at last!

The shortlisted works for 2010 were:

Steven Carroll, The Lost Life (HarperCollins)

Enza Gandolfo, Swimming (Vanark Press)

Cate Kennedy, The World Beneath (Scribe)

Kristina Olsson, The China Garden (UQP)

Susan Varga, Headlong (UWA Publishing)

with the following two works being highly commended:

Judith Lanigan, A True History of the Hula Hoop (Picador)

Lili Wilkinson, Pink (Allen & Unwin)

And the winner was:

Kristina Olsson, The China Garden (UQP)

| Peter Goldsworthy, author of Everything I Knew, has published a new collection of eight stores titled Gravel. He was interviewed by Angela Meyer for the "LiteraryMinded" weblog. The book is published by Penguin Books, under the Hamish Hamilton imprint. |

You're skilled at capturing that moment of erotic awakening, in 'The Nun's Story', and also in Everything I Knew. It's the kind of topic that draws the reader in through memory, the senses and the imagination. Is the best kind of art, for you, something that stirs the intellect, emotions and physical body all at once?As a child I was pretty often covered in various forms of gravel rash - falling off bikes, tripping in the school playground, which always seems to be covered with bitumen - so I cringe just a little every time I see that cover.

Exactly. Too much literary fiction is pure confection - all head; too much popular fiction is cheap emotions - all heart. There are great exceptions; there is nothing human - nothing of the heart - in Borges' best stories, and they are wonderful. But he knew to keep them short; he would never risk boring us with a novel. I want - unhumbly - to speak to all the organs at once. I've often written about this - as essay called the Biology of Literature, for one - how writing can make us weep and laugh of course, but can make the goosebumps rise (Robert Graves' test of great poetry), or make our hairs stand up on end, or fill us with awe, or stop us sleeping for days.

Which story in Gravel was the most difficult to write, and why?

Hard to say. They are always a mixture of pain and pleasure. 'Sometimes pus, sometimes a poem - but always pain', the poet Yehudi Amichai wrote. 'Shooting the Dog', perhaps - a story that was given to me by my wife Lisa, from her days as a young teacher in the bush. Or the last one, on the love between a middle-aged man and a school girl.

DOWN THE YEARS, by Margaret Herron. - Hallcraft, Melbourne.

Since the title of this book means nothing in particular, the subject would not be immediately apparent if it were not for the fact that the dust-jacket (which is no place for a sub-title) carries the words in small type, "The Life Story of C. J. Dennis, as told by his wife."

That announcement, in fact, is somewhat misleading, for the narrative has too many gaps, and in general is much too slight, to be regarded as "the" life-story, or even "a" life-story, of its subject. It might well have been strengthened by a few illustrations, a bibliography, and perhaps a chapter or two of reminiscence by Dennis's competent artist associate, Hal Gye.

Presumably, "Down The Years" is the outcome of a resolution reached soon after the death of Dennis, when a memorial committee commissioned his widow to write a 'life." That was 15 years ago. In the meantime much material discussing the writings and character of "Den" has been published, and thus a number of the points made in this book , such as those dealing with the origin of "The Sentimental Bloke," are not new.

Necessarily, however - necessarily in the case of a widow writing about her husband - the little volume contains, in certain parts of its 88 pages of wifely chatter, various fragments that are fresh and interesting.

Among these items are one or two brief notes from Henry Lawson, some amusing personal impressions of Dennis's lavender and-lace aunts, and a frank account of how the author reacted to the desire of her versatile husband to keep at different times a household cow and a few prize fowls.

Various comments in the book give rise to a couple of intriguing questions (1) Is a poet's wife the best judge of her husband's character? (2) How much should a widow tell'?

Possibly the reply to the first question should be, "Not necessarily," and to the second, "It all depends..."

Mrs Dennis's domestic assessments are somewhat forthright. She disputes a suggestion, made by some of "Den's" associates, that he occasionally showed a strain of affectation, but, on the other hand, she declares that his tastes were "always extravagant," that he displayed "primness" at times, and that he had a "casual attitude" and "periods of aloofness" that grew worse in later years.

Whatever may be said of these judgments, mere males who knew "Den" will be on his side in the matter of the cow and the fowls.

First published in The Sydney Morning Herald, 2 January 1954

[Thanks to the National Library of Australia's newspaper digitisation project for this piece.]

Elizabeth Speller in "The Independent": "David Malouf's book is born of war. He was first gripped by the stories of the eighth-century BC Iliad as a Brisbane schoolboy in 1943, living among sandbagged buildings and watching constant American troop movements north to the battles of the Pacific. He began this novel 60 years later, drawing on that ancient tale of war just a year or so after the destruction of the World Trade Centre...It is not surprising that his take on extreme and seemingly inexorable violence should be told from the sidelines and should speculate on the back-story of the Trojan war: on bruised humanity, of small glances and fancies, hopes and fortunes dashed, rather than the clash of weapons and heroic egos. But the themes of this apparently simple, yet immensely moving, modern novel are still vast: loss, forgiveness, love and redemption."

David Hebblethwaite on his "Follow the Thread" weblog: "What I take away the most from Ransom is the portrait of a world which is not my own. I haven't the knowledge to judge how authentic is Malouf's depiction of ancient times (and it's a legendary version, anyway), but it's convincing enough for me. This is a society to which the idea of things happening by chance is an alien concept, where everyone is bound to the stations given them by the gods, even a king: he must be seen to be a king, becoming more 'object' than individual - which is why Priam's plan to disguise himself causes such controversy. It takes some effort to connect with this world that thinks so differently, and so it should - but the reward is a fully immersive tale."

Tom Holland in "The Guardian": "If Classic FM published fiction, then Ransom is the kind of novel that would surely result. David Malouf's reworking of the climactic episode of the Iliad demonstrates that epics are no less susceptible than symphonies to being chopped up and repackaged in accessible, bite-size chunks...No one, and certainly not a writer as talented as Malouf, can go far wrong with material like this. As in the Iliad, so in Ransom, the moment when Priam finally meets Achilles and states his mission brings a lump to the throat. Both the lyricism of his prose and the delicacy of his characterisation enable Malouf to avoid the risk of bathos that so often stalks novelists when they try to update epic. He also manages to avoid another tripwire with his treatment of the gods: the immortals, though they manifest themselves throughout the novel, tend to do so elliptically, appearing on the margins of Priam's vision, or else by revealing personal knowledge of a character that no mere mortal could be expected to know."

Darryl Accone mentions Malouf's novel in an essay entitled "Of Walls, Wars, Food and Games" in the "Mail and Guardian": "Malouf moves imaginatively and thoughtfully beyond Homer, the precursor he always respects. There is no expedience to his embellished and enlarged tale, which concentrates on Priam's attempts to recover Hector's body from Achilles. Ransom has been 66 years in the making, from a rainy afternoon in 1943 when Malouf first encountered the story of Troy. For him, and for us, it has been worth the wait."

Edmund White in "The New York Times": "Mr. Malouf is an Australian writer and perhaps his fascination with the wisdom of "barbarians" comes out of his interest in the Aborigines of his country; Mr. Malouf's masterpiece, "Remembering Babylon," is about a 19th-century white adolescent sailor who falls overboard and spends years living among the Aborigines. He nearly forgets English and adopts the culture of the tribe he lives with..."Ransom" is a similarly serious, often beautiful examination of the contrast between the simple sincerity of the carter and the strangely abstract existence of the king. It is dignified and thought-provoking -- but it doesn't seem to me to be exactly a work of art, to be fully realized and embodied in the lives of its characters. It is more a metaphysical inquest than episodes from messy, contingent experience."

Articles by Malouf

In December, Malouf wrote a piece for The Australian newspaper calling for the preservation of Yungaba, an historic building in Brisbane that was threatened with demolition.

"The Sydney Morning Herald" published an extract from Malouf's essay On Experience, which was to be published by Melbourne University Press.

Interview

Anna Metcalfe in "The Financial Times".

Others

The Red Room Company has video-taped a talk by David Malouf titled "The Wordshed, David Malouf in the House of Writing."

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

Part 5

Part 6

Each part runs about four minutes.

The author paid a visit to homeless Clemente students at Mission Australia, who are studying Remembering Babylon.

Wet Ink is pleased to celebrate five years of publication by announcing the Wet Ink Short Story Prize. First prize is $3,000, publication in the March 2011 issue of Wet Ink, and a year's subscription to the magazine. Two highly commended entries will each receive $100, publication in the March 2011 issue of Wet Ink, and a year's subscription to the magazine.

Guest judge Peter Goldsworthy - one of Australia's best short story writers - and Wet Ink's fiction editors Sally Breen and Emmett Stinson will judge the entries.

There is no set theme, and the closing date is 31 August 2010. An entry form available from the magazine, or from the Wet Ink web site at www.wetink.com.au

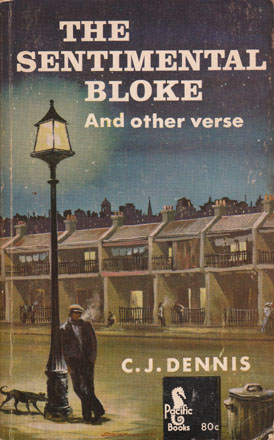

The Sentimental Bloke and Other Verse by C. J. Dennis, 1950

Pacific Books edition 1967

Note: this collection was first published by Angus and Robertson in 1950 and is, as far as I can tell, the first major use of a cover for Dennis's Bloke which doesn't feature Hal Gye's cherubs. The artist here is unidentified.

What inspired "The Good Window"?

I'd had a few of the story's elements kicking around in my mind for a while, but a flight I took from Tasmania home to Adelaide last year was the catalyst I needed to bring them all together. Basically, we had just taken off and the plane had made a really sharp turn--so sharp that all I could see out my window was vibrant green grass, dense forests, and sparkling waters. No horizon, just ground. And since Adelaide's been experiencing intense drought for years, Tasmania's lush landscape came as a shock. It was such a contrast to what I'd gotten used to seeing at home! So, since I generally tend to think morbid thoughts at the beginning of my flights, I looked out at this gorgeous view and thought, 'If the plane crashed right now, this would be the last thing I saw. Apart from the plummeting towards death part, that wouldn't be half bad.'

Once the plane righted itself, I started thinking about how our perspectives--literally, what we see when we look out at the world--influence the way we experience life. From there it was a quick step to: What if a character's world view was mostly based on what she saw outside her window each day?

You can also read another interview with the author which was conducted as part of the 2010 Australian Specfic Snapshot.

My youth came speading back to me;

And once again a chord was struck

Within my breast. I wished him luck,

That jubilantly piping bird I heard at Booralee.

Night's mantle over all was spread,

It was the hour before the dawn;

And, as I looked up at the sky,

The happy songster to descry,

The moon that erst her light had shed,

Had now that light withdrawn.

But still the lark sang gaily on,

Nor heeded he the cloud-dimmed moon;

Reverberant, the air replied.

As though it felt the minstrel's pride

One grand crescendo, and 'twas gone,

That joy-compelling tune.

Ah! blithesome bard of Booralee,

Why did you cease so soon your song

Had you but known the load of care

That weighed me down, the vibrant air

Might echo still the melody

For which my heart doth long.

First published in The Sydney Morning Herald, 12 December 1925

Days of Lawson and Lambert

What a wonderful place was the Sydney of the 'nineties! The sunshine was more mellow then, and the wattle blossom more golden or perhaps it was that they appeared so, seen through the eyes of youth. But however that may be, the foreshores of the harbour were undoubtedly more beautiful than they are to-day, for there was still bush where there are streets and houses now. Fine old homes, too, many of which have disappeared were still standing In spacious grounds which have long since been cut up into building blocks. Manly was then not even a village, and Watson's Bay, with its scrub and its flannel flowers, was a favourite picnicking ground. In Sydney itself steam trams puffed their way towards the pleasant suburb of Leichhardt, whilst Potts Point was a reserve for the rich and fashionable. Hansom cabs abounded, but young ladies who did not wish to be considered "fast" did not drive in them alone, any more than they sat upon the tops of horse-drawn omnibuses. There were no skyscrapers in those days, but visitors from New Zealand gazed with awe and admiration at the two cathedrals, at the Town Hall and the Post Office and at the Equitable Building in George-street. Lower down, towards the Quay, where the big steamers berthed, there existed a Chinatown, fearsome yet fascinating.

How delightful seemed King-street then, with Quong Tart's tearooms, and shops where flowers, unknown to dwellers in colder climates, were arranged with exquisite taste, or where strange fruits, such as guavas and mangoes, were plied beside familiar apples and pears! Living was unbelievably cheap in those days, and no peaches are so luscious now as those which street vendors sold for /2 a dozen. Truly, Sydney seemed a wonderful city to a girl straight from school in a small New Zealand town. And then the young men who were doing wonders with their pencils or their pens! Frank Mahony was drawing Australia as it was, and George Lambert had not yet gone off to Paris and London. Will Ogilvie was in New South Wales singing of Fair Girls and Gray Horses; Victor Daley was in the brief sunshine between the Dawn and the Dusk, and the Hidden Tide was sweeping Roderic Quinn on to the magic shores of poetry.

The women of New South Wales were enfranchised later than their sisters across the Tasman, but some of them, too, were doing wonderful things. Mary Gilmore was off to Paraguay, the dreams of Louise Mack were already in flower, and amongst the musicians there was Mme. Charbonnet-Kellermann. Upon the stage, Nellie Stewart, who died recently, enchanted her audiences before Florence Young and Violet Varley, who died so long ago. Then, in the early nineties there was Mr. Robert Brough and an altogether admirable company at the Criterion.

A Valued Volume

Another woman of singular ability and energy was actually running a newspaper at 402 George-street, and there, from that small and dingy office of the "Dawn," she published a small volume of "Short Stories In Verse and Prose," by her son, Henry Lawson. It contains the most beautiful of his tales, the most beautiful of all Australian tales, "The Drover's Wife." No one could have foreseen then how much sought after this volume was to become, and it was in the lost year of the nineties that Louisa Lawson gave a copy of the then unsold, to a New Zealander as she sailed for Europe from Sydney one burning February day. Books are lost and books are stolen every week, and every month or thereabouts books are borrowed, never to be seen again. But this volume, so small, so insubstantial in its paper cover, was to lead a charmed life. It was to go three times round the world, to lie safe in a Belgian attic during the war, whilst the library at Louvain went up in smoke and the Cloth Hall at Ypres was battered into dust, and finally to return to Sydney, whence it came.

It is nearly 40 years since Henry Lawson's "Short Stories" were issued by his mother, and each year since 1894 his fame has grown, outspreading the limits of his native land, and now the statue of this son of Australia stands upon Australian soil, beneath Australian trees. Henry Lawson himself is gone, and George Lambert is gone also, but their work remains. Yet is it incomplete if the living are content to remember the past alone, to honour only the dead. All created work is in itself - or should be - creative; and these men of vision and achievement laid down a lighted torch for others to take up. The statesman, the farmer, the manufacturer, the labourer all these are necessary for the making of a nation, but it is the artists who crown it with a wreath of imperishable laurel in the sight of all the peoples.

[Thanks to the National Library of Australia's newspaper digitisation project for this piece.]

The shortlisted works are:

Long Fiction

- A Book of Endings by Deborah Biancotti (Twelfth Planet Press)

- Red Queen by H. M. Brown (Penguin Australia)

- "Wives" by Paul Haines (X6, Coeur de Lion Publishing)

- The Dead Path by Stephen M. Irwin (Hachette Australia)

- Slights by Kaaron Warren (Angry Robot)

Edited Publication

- Grants Pass, edited by Jennifer Brozek & Amanda Pillar (Morrigan Books)

- Festive Fear, edited by Stephen Clark (Tasmaniac Publications)

- Aurealis #42, edited by Stuart Mayne (Chimaera Publications)

Short Fiction

- "Six Suicides" by Deborah Biancotti (A Book of Endings)

- "The Emancipated Dance" by Felicity Dowker (Midnight Echo #2)

- "Busking" by Jason Fischer (Midnight Echo #3)

- "The Message" by Andrew J. McKiernan (Midnight Echo #2)

- "The Gaze Dogs of Nine Waterfalls" by Kaaron Warren (Exotic Gothic 3)

The death is announced of Mrs. Campbell Praed, the novelist.

Mrs Praed was born in Queensland 1851, and is the daughter of Mr. T. L. Murray-Prior. She was educated mainly at Brisbane, and previous to her marriage saw a great deal of the social and political life of Queensland. On August 29, 1872, she married Arthur Campbell Bulkley Mackworth Praed, son of a banker in Fleet-street, and nephew of the poet, Winthrop Mackworth Praed. Mr. and Mrs. Praed lived at their station on Curtis Island, Queensland, until 1876, when they came to London. In 1880 she published her first novel, "An Australian Heroine," which has been followed in rapid succession by a number of works. many of which are entirely Australian in character: such as "Policy and Passion" (or "Longleat of Kooralbyn"), "Moloch," "The Head Station," "Affinities," "Australian Life," "Black and White," "Miss Jacobsen's Chance," "The Bond of Wedlock" (subsequently dramatised by the author, and produced by Mrs. Bernard Beere, under the name of the heroine, "Ariane "), "The Brother of the Shadow," "The Soul of Countess Adrian." Mrs. Praed has collaborated with Mr Justin M'Carthy, MP, in a series of novels dealing mainly with English political and social life, but some parts of which are distinctly Australian. These are "The Right Honourable,'' "The Ladies' Gallery," and "The Rival Princess." Mrs. Praed is generally recognised as the most brilliant and successful of Australian novelists. Her descriptions of the scenery of her native land are unsurpassed, and Australians cannot he blamed for thinking her work, which deals with the life, character, and scenes of Queensland, to be of a higher and more enduring kind than the descriptions of London ephemeral fashions, social, political, or religious, which she occasionally essays. Some few years ago Mrs. Praed paid a visit to the United States, and subsequently wrote a series of articles on her Transatlantic experiences in "Temple Bar." She has frequently written for the magazines, English and American, and been a contributor to the series of short stones written by "Australians in London," from "Oak-Bough and Wattle Blossom" (1858) to "Cooee" (1891).

First published in The Sydney Morning Herald, 7 November 1901

[Thanks to the National Library of Australia's newspaper digitisation project for this piece.]

Note: It is interesting to reflect that Campbell Praed actually lived until 1935. Her husband died in 1901, and it is possible that the SMH just got the two confused.

Campbell Praed's biographical page.Update: the newspaper printed the following the next day:

MR. CAMPBELL PRAED..

LONDON, Nov. 5.

The death is announced of Mr. Arthur Campbell Praed, formerly of Queensland.

Owing to the mutilation of a word in the telegraphic message, the announcement was yesterday interpreted as referring to Mrs.Campbell Praed.

According to her website:

May 2010 sees the hardback publication of The Ambassador's Mission, the beginning of the Traitor Spy Trilogy, which takes up the action a generation after the events in The High Lord.

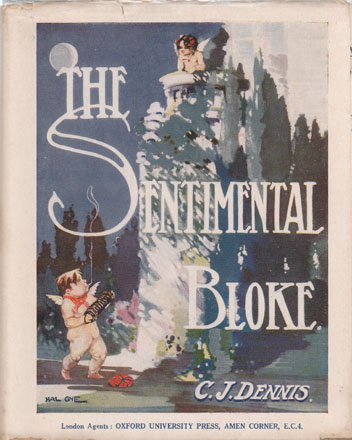

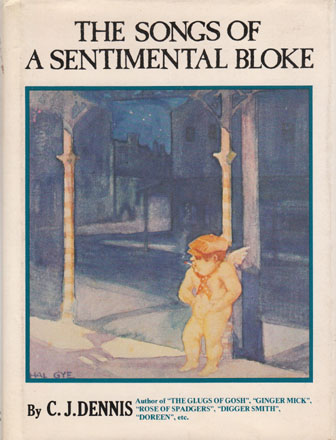

The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke by C. J. Dennis, 1915

Angus and Robertson edition, 1919

Cover by Hal Gye

This edition was the seventeenth of this verse novel. Published on 1st October 1919 - just a touch under four years after the first edition - it brought the total number of copies printed to 100,000.

Fair lays, young with Elizabethan dew,

You won from Rime's rare fields, known to how few

Who scatter Fancy's lyric seeds along!

Your darling love, the sea, with tall ships strong,

Perchance gave you your gallant, boyish view.

No mere girl-writer you! Your vision blue

Swept far horizons with a rollicking throng.

Yet am I stretched apart this April day

With stinging tears for Poesy's sad loss;

My heart cleft open with a sorrow wide,

As once it knew when midst blithe childhood play,

I lay grief-strlcken on my fairy moss,

Because a little book-girl, "Judy," died.

First published in The Sydney Morning Herald, 5 April 1930

ON THE HORNS OF A DILEMMA.

A writer in the "London Mercury" calls attention to the fact that the Australian writer finds himself placed on the horns of a dilemma. As a patriotic citizen, his first aim is to reach the hearts of his own countrymen through the medium of the Australian publisher. It is only natural that he should also yearn for wider publicity, and turn longing eyes towards the reading public of the Old World. Here arises the dilemma -- how to realise both laudable ambitions. He finds to his dismay that a book published in Australia rarely meets the eye of the English reader. What is the cause? Briefly, that the Australian novel which, under different conditions, might have been numbered among the "best sellers," remains unknown because Australian publishers do not advertise sufficiently in the British Press. With things Antipodean booming in England, and social success on the crest of the wave, the expression of the Australian mind is comparatively unknown. The "London Mercury" points out that the valuable outline of Australian literature by Netty Palmer [sic], published in Melbourne, which "ranks with Stopford Brooks' Primer of English Literature," is unknown in the Motherland. This, the first outline that has ever appeared, would prove a most valuable guide to English students, although the title might possibly provoke the inquiry, "Does an Australian literature exist?"

Of books and writers there are no end, but has Australia existed long enough to present to the world the special type which constitutes a national literature? There is nothing invidious in this question. When we consider the centuries of conflict, endeavour, achievement, of strife, between nations, and factions, and religions, of passionate thirst for particular ideals, of romantic happenings, which have been the inspiration of European literature, we are forced to realise that, great as has been the material progress and high endeavour of the Australian people, they cannot, in the short space of their history, look for inspiration from similar sources. Descriptive novels dealing with sectional interests -- bushranglng, pioneering, mining, shearing, convict days -- do not represent the nation as a whole. The birth of the soul of Australia must precede that of its literature. In the process of its evolution, the books which are "milestones on the road" should prove of deep interest to all English-speaking readers -- if, and it is a large if -- they could only got hold of them.

It is noteworthy that Mrs. Palmer takes the year 1900 for her starting point, excluding such descriptive writers as Marcus Clarke and Rolf Boldrewood. These were replaced by "the intimate and natural short story," of which Henry Lawson proved himself a master. She contends that the quality of the novel since 1920 is that of the short story -- "vigorous and abrupt without the suavity of the conventional novel." Among "the personal" books dealing with the life of adventure, she mentions Mrs. Gunn's "We of the Never Never." This delightful book is, happily, well-known in England, as are the novels by "Ada Cambridge," and a few tales of the "gold rush." The intense interest in the new outlet for the spirit of adventure felt in England in the early fifties caused the demand for any sort of story which told of kangaroos, and kookaburras, and the vicissitudes of the early settlers. The library of the British Museum possesses files of yellow local newspapers wherein are printed letters sent by proud parents which they have received from adventurous sons. These constitute a true record of the beginnings of Australian hlstory.

Mrs. Palmer finds the Bush Ballad well established at the close of the nineteenth century, "although the value of its work lay in its zest rather than in its style." A great deal of Australian verse has been produced by women, but "the best cradle song" has been written by a man, and "two men have produced the best child poem." On the other hand, "the best prose stories for children have been written by women." We regret Mrs. Palmer did not mention in her outline "The Education of Clothilde," which was published as a serial eighteen or twenty years ago, and, strange to say, has not yet appeared in book form.

It is regrettable that such a valuable guide as Mrs. Palmer's outline should not be in the hands of oversea readers. The British public, which is as ready to follow sympathetically the literary progress of Australia as to pay homage to its material development, fails for lack of opportunity. We look forward confidently to the day when books by Australian writers will be advertised side by side with those of the "best sellers" of Great Britain. A llttle more enterprise on the part of Australian publishers is all that is required.

First published in The Sydney Morning Herald, 21 August 1926

[Thanks to the National Library of Australia's newspaper digitisation project for this piece.]

Note: the Nettie Palmer work referred to here is Modern Australian Literature, 1900-1923 which was published by Lothian in 1924, and reprinted - though I am not sure if it was in its entirety - in Nettie Palmer: Her Private Journal Fourteen Years, Poems, Reviews and Literary Essays published by UQP in 1988.

The Education of Clothilde, by Sydney Partrige and Cecil Warren, was serialised in The Leader newspaper beginning 3 November 1906. It does not appear to have been reprinted.

Note: The first edition of C.J. Dennis's The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke was published in September 1915. Within a year it had passed through 9 editions and the numbers of copies in print was 51,000. In honour of reaching that mark, Dennis provided a new preface to the book. He refers to the original foreward written by Henry Lawson and published here last week.

Nearly a year ago Henry Lawson wrote in his preface to the first edition of these rhymes: "I think a man can best write a preface to his own book, provided he knows it is good." Now, and at the end of some twelve months of rather bewildering success, I have to confess that I do not know. But I do know that it is popular, and to write a preface to the fifty-first thousand of one's own book is rather a pleasant task; for it is good for a writer to know that his work has found appreciation in his own land, and even beyond.

But far more gratifying than any mere record of sales is the knowledge that has come to me of the universal kindliness of my fellows. The reviews that have appeared in the Australasian and British Press, the letters that have reached me from many places -- setting aside the compliments and the praise -- have proved the existence of a widespread sympathy that I had never suspected. It has strengthened a waning faith in the human-kindness of my brothers so that, indeed, I have gained far more than I have given, and my thanks are due twofold to those whose thanks I have received.

I confess that when this book was first published I was quite convinced that it would appeal only to a limited audience, and I shared Mr. Lawson's fear that those minds totally devoted to "boiling the cabbitch stalks or somethink" were many in the land, and would miss something of what I endeavoured to say. Happily we were both mistaken.

These letters of which I write have come from men and women of all grades of society, of all shades of political thought and of many religions. But the same impulse has prompted them all, and it is good for one's soul to know that such an impulse moves so universally. I created one "Sentimental Bloke" and he discovered his brothers everywhere he went.

Towards those English men of letters who have written to me or my publishers saying many complimentary things of my work I feel very grateful. Their numbers, their standing and their unanimity almost convince me that this preface should be written. But even the flattering invitation of so great a man as Mr. H. G. Wells, to come and work in an older land, does not entice me from the task I fondly believe to be mine in common with other writers of Australia. England has many writers: we in Australia have few, and there is big work before us.

But when I stop and read what I have written here the thought occurs to me that, even in this case, the man has not written a preface to his own book, and Mr. Lawson's advice is vain. For I have a picture before me of a somewhat younger man working in a small hut in the Australian bush, and dreaming dreams that he never hopes to realise-dreams of appreciation from his fellow countrymen and from great writers abroad whose works he devours and loves.

And I, the recipient of compliments from high places, of praise from many places, of publisher's reports about the book that bears my name - I, who write this preface, have a kindly feeling for that somewhat younger man writing and dreaming in his little bush hut; and I feel sorry for him because he is out of it. Later perhaps, when strenuous days are over, I shall go back and live with him and tell him about it, and find out what he thinks of it all - if I can find him ever again.

Melbourne, 1st September, 1916.

Children's Literature Award (for a published children's book, fiction or non-fiction)

Tales From Outer Suburbia by Shaun Tan (Allen & Unwin)

Fiction Award (for a published novel or collection of short stories)

Ransom by David Malouf (Knopf/Random House)

Innovation Award (for a published book which departs from the conventional use of genre by borrowing elements from a number of genres such as fiction, non-fiction, biography, autobiography, poetry or cultural criticism)

Barley Patch by Gerald Murnane (Giramondo)

Non-Fiction Award (for a published work of non-fiction demonstrating a command of the subject as well as a fluent and outstanding literary style)Stella Miles Franklin: A Biography by Jill Roe (Fourth Estate/HarperCollins)

John Bray Poetry Award (for a published collection of poetry)

The Other Way Out by Bronwyn Lea (Giramondo Poets)

Premier's Award (for the best of the above categories)

Tales From Outer Suburbia by Shaun Tan (Allen & Unwin)

South Australian Recipients

Jill Blewett Playwright's Award

This Place by Nina Pearce

Unpublished Manuscript Award

End of the Night Girl by Amy T. Matthews

Barbara Hanrahan Fellowship

Potatoes in All Their Glory and How to Win at Democracy by Patrick Allington

Carclew Fellowship

Alone With Me by Nicole Plüss

The full shortlists can be found here.

The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke by C. J. Dennis, 1915

Cover by Hal Gye

Angus and Robertson edition, 1985