Posts have been a tad scarce over the past few days. I'm finishing up one job and moving on. This has meant a lot of cleaning up at work and no time for anything else. Hopefully service will be resumed within the next few days.

June 2006 Archives

Will Dyson saves you the trouble of reading through the ever increasing library of the novels of the strong silent man.

First published in The Herald, 10 April 1926

The program for the 2006 Melbourne Writers' Festival isn't out yet but the organisers have realised a few titbits via their mailing list. It appears that crime will be big this year - crime and thriller writing that is. Booked to appear so far we have Peter Temple, Shane Maloney, Kerry Greenwood, Jane Clifton, James Phelan, Jack Heath, Barry Maitland, Dame Stella Rimington, Jason Starr, Robert Goddard and Robert Wilson. The Festival runs from August 25th to September 3rd and the program will be released in late July.

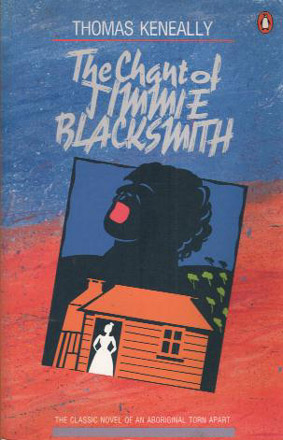

The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith by Thomas Keneally, 1972

(Penguin 1989 edition)

Cover illustration by Michael Fitzjames. Cover design by Jacqui Young.

Is it winter? Is that the reason for the lack of new Australian books around at present? Do we only read on the beach? Well, not this little black duck. I don't go to the beach. Give me a warm fire, a good light and a full glass of muscat and I'm in heaven. No flies, no sand, no sunburn. In any event the literary activity in Australia is about as cold as the weather. Though there are a few gems here and there.

The Age

The new biography of Kylie Tennant (author of such novels as The Battlers and Ride on Stranger) by Jane Grant is reviewed by Peter Pierce. The book is the second in a series, being produced by the National Library of Australia, titled An Australian Life.

"The literary history of the inter-war period in Australia was in significant part the work of such female authors as Tennant, Eleanor Dark, Jean Devanny, Katharine Prichard (with the latter two, Tennant bitterly fell out over politics). Their novels depicted working and underprivileged Australia to the reading public, many of whom knew little of it."

Short notices are given to: Time for Change: Australia in the 21st Century edited by Tim Wright: "In this spirited collection of essays from a diverse range of public figures, Michael Kirby argues for dissent if democracy is to flourish, Pat O'Shane proposes a separate portfolio of Aboriginal Affairs to address problems in the indigenous community, and Julia Gillard advocates the rebuilding of the public realm in health care"; and Eddie's Country: Why Did Eddie Murray Die? by Simon Luckhurst: "Both stirring and bleak, Eddie's Country is about an epic struggle for justice and the depths of denial that allow such miscarriages of justice to prevail".

The Australian

Marion Halligan kicks of this week's literary offerings with a piece titled "Sex and the Singular Woman". Taking Sonya Hartnett's latest offering, Landscape with Animals (published under the name Cameron S. Redfern), she looks at the Bad Sex in Fiction Award, Peter Craven's reaction to Hartnett's novel (which I covered here), reviewer's reactions to her own books, and in the middle of all that, produces a review of the Hartnett novel. She gets the jokes, the melodrama and deliberate exaggerations:

"This is such good writing. It is the work of someone who loves words, who loves writing and reading, who understands how language works and how words can be put together to touch the heart and the mind and make the reader glad that there are still people in the world who can do this.

"And yes, it is about sex; why not? Why should that challenge people, even threaten them? Especially men reading about women doing it. How useful it would be if they could admit this feeling, and examine it. What about a good sex in fiction award? For good writing about good sex. Wouldn't that be fun?"

So, that's three reviews so far, one male against and two females for.

The novelist Alan Gold takes a big swipe at John Pilger's Freedom Next Time, concluding that it "can best be defined as a gigantic kvetch by a man who rails against a world that isn't run the way he wants. Only a blind neo-con would argue that all's well with the world; only a fool would argue that the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have brought universal benefits; but only a rabid Savonarola such as Pilger would argue that the world's ills are the responsibility of the US and its allies."

Short notices are given to: Monica Bloom by Nick Earls, in whose main character the author "convincingly creates a reflective teenage narrator to show how even the worthwhile pursuit of love is often beyond our means"; Monkey Undercover by Garielle Lord, who "is a favourite with adult readers and her fast dialogue, taut narrative and charismatic charcaters - without the violence - have fashioned an exciting, suburban adventure story bound to be a success with younger readers"; Allie McGregor's True Colours by Sue Lawson "who shows that [a miserable teenage life] can only get better and that, despite sometimes being a nuisance, familial love is all we have in the end"; The Nightfish by Helen McCosker: "Using beautifully toned paintings that sweep across the page, Helen McCosker's first picture book is an environmental fable with only the occasional tangled sentence that doesn't stand up to being read aloud"; Weeping Waters by Anne Marie Nicholson whose "fiction debut augurs well; importantly, she's taking on big subjects and big themes"; and The Stone Angel by Katherine Scholes: "What she has written, with precision, is a novella stretched across a very large frame and wrapped in good writing".

The Broken Shore by Peter Temple has now been published in the UK and is starting to garner some reviews. In "The Independent" Mark Timilni is certainly impressed with the book: "The Broken Shore is a sad, desolate novel, as Temple chronicles the death of an area, on the down for the locals, but the up for the rich who come to play. It's a stone classic. Hard as nails and horrible, but read page one and I challenge you not to finish it."

In "The Daily Telegraph", Siddartha Deb finds a lot to like about Theft by Peter Carey: "Theft is a work of art that successfully reflects upon the conditions in which art is created, and one can't complain if it demands of the reader an ability to separate the slightly derivative skin from its pulsating, inimitably authentic, core."

Kate Grenville reviews Tom Keneally's The Commonwealth of Thieves in "The Guardian": "For anyone who has an uneasy feeling that their grasp of early Australian history is less than absolutely firm (and that includes a great many of us), The Commonwealth of Thieves is a great bluffer's guide. The book gives an overview and makes a clear sequence out of all the many different sources...[the book] is a great read and a useful scholarly resource. Excellent chapter notes, an extensive bibliography and the index make Keneally's journey transparent, and allow further exploration in the sources for an interested reader."

Keneally's book is also reviewed in "The Times" by Carmen Callil: "Keneally has always had a grand talent for the telling of a tale. His rattling account of the genesis of his native city is one of his very best."

Tim Flannery's book The Weather Makers is still attracting reviews with Richard Girling, in "The Sunday Times", casting an eye over the book, in tandem with two others on global warming: "Flannery's book is nothing less than a user's manual for the planet... He is a master of cause and effect, explaining, for example, why the warming of the Indian Ocean causes drought in the Sahel. Along with the horror, he serves a generous helping of fine-grained detail that improves our understanding of the natural world even as it increases our anxiety for its future."

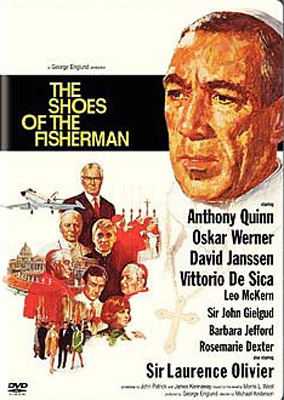

The Shoes of the Fisherman 1968

Directed by Michael Anderson

Screenplay by James Kenneway and John Patrick from the novel by Morris West

Cast: Anthony Quinn, Lawrence Olivier, Oskar Werner, David Janssen, Leo McKern and John Geilgud

In Memory Of Will Dyson and W.T.B. McCormack

Two treasured friends have slipped away,

Mayhap to peace veiled from our eyes;

And one was simple as the day,

And one complex and keenly wise,

And both of them I sorely miss.

These mates, now passed beyond our ken,

For both of them were one in this:

They practised friendship as true men.

A friendship, not for me alone,

But for that variant world each knew,

As variant worlds must e'er be known

To men unlike, as were these two.

Yet both were like in that each fought

His fight 'gainst poverty and pain;

And both gained laurels, dearly bought

These friends I may not see again.

And each wrought well that he might give

His whole life to his chosen plan;

Each lived as worthy men e'er live:

In service of his fellow-man.

And one he served by splendid deeds

That thro' long years shall live again;

And one strove for his fellows' needs

With keen shafts from a brilliant brain.

Each had his meed of human praise

Such as sincerity must win;

One was a torch to light far ways,

The other was a javelin,

And each served well as he knew how

To ease man's burden of distress,

These vanished friends I grieve for now

Because I have found loneliness.

The count of years may ne'er condemn

Such friends or their stout constancy,

And part of me has gone with them,

Yet they leave one great gift with me;

Such gift as few men come to prize --

So feckless is man's heart and mind --

Till friend, but never friendship, dies:

A faith upheld in humankind.

Two treasured friends have slipped away,

Men as diverse as men can be;

Yet are they one to me today,

These friends I may again ne'er see.

One in fine service, one in faith,

One in a friendship, richly rare,

So seem they, till I, too, a wraith,

Seek for them, haply, otherwhere.

First published in the Herald, 28 January 1938

Note:

Will Dyson was a writer

and artist (a brother of Edward Dyson and brother-in-law of Norman Lindsay), W.T.B. McCormack was a civil servant, civil engineer, and soldier.

Jason Steger in "The Age" sums up the response right up front: "Most pundits fancied the novel about the early days of white settlement for this year's Miles Franklin. After all, it had already won both the Commonwealth Writers' Prize and the NSW Premier's Prize...Last night, the novel set in early 19th-century NSW duly won Australia's most significant literary prize. But it wasn't The Secret River, Kate Grenville's much-acclaimed novel and the hot favourite; it was Roger McDonald's The Ballad of Desmond Kale...It was the fifth time one of his novels had been shortlisted for the award, and McDonald admitted he was 'gobsmacked' when told of his success."

In "The Australian", Murray Waldren reports that award judge Morag Fraser said the decision was unanimous. He also concentrates on the fact that McDonald won, rather than that Grenville lost, though he does acknowledge McDonald's history with the award: "Four times before, the writer, based in Braidwood, NSW, had been shortlisted for this most prestigious and richest award on the Australian literary calendar, and he feared he was fated to remain a perennial bridesmaid."

Catherine Keenan gives a nod to Grenville along the way to congratulating McDonald, in "The Sydney Morning Herald", and notes: "It was a particularly distinguished win given the strength of this year's shortlist".

In Brisbane's "Courier-Mail", Jonathon Moran produces the shortest report of the four but does give probably the best quote from the winner: "It is something that you hope for but you can never guarantee it will become a reality. It is a terrific prize to win, and it gets the recognition and the readership that every author craves."

In news just to hand, it has been announced that Roger McDonald is the winner of the 2006 Miles Franklin Award for his novel The Ballad of Desmond Kale. This might come as a bit of a surprise to some people as it wasn't widely reviewed and as Kate Grenville was generally considered the front runner. It certainly comes as a surprise to me as it's the only one of the five I have yet to read. Bugger.

Regular correspondent Ron writes to inform me that The Book Thief, the popular new novel by Markus Zusak, has been optioned by Fox 2000 for film adaptation. No further details available as yet. It just gets better and better for him.

As this is the day that the winner of the 2006 Miles Franklin Award is announced, "The Age" features two articles about the award. Jason Steger, literary editor of the paper, asks "Is it Time for a New Chapter?" and Jane Sullivan, reporter on matters literary, discusses "The Power of the Prize". My choice of winner this year: Kate Grenville for The Secret River, though I wouldn't be at all surprised if Brenda Walker's The Wing of Night runs a close second. Don't worry, after tomorrow this will all go away and we can forget about it for another year.

|

'P S,' they said.

And 'Vanessa'.

Or sometimes 'Ness'.

PS. PS. PS. PS. Ness. Ness. Ness.

It sounded through his half sleep like surreptitious mice foraging through tissue paper. It was as mysterious as the lateness of the hour - after nine o'clock - and only as far away as the kitchen door, ajar so as to hear him if he should call to them or have a nightmare.

He turned in bed, listening to the whispering undertones, as steady and continuous as a tap left running and broken only by a cough or sometimes a chair scraping back on the linoleum; then a dish being taken from a cupboard and now and then a voice would catch on fire and break adrift from the murmurings, but always with the same word, Vanessa, said sharply like hitting a brass gong at dead of night and then someone would say, 'Shhh, was that him? Did he call out?' and tiptoeing would startle the old floorboards while a shadow grew larger and larger on his wall; bent to hear if he was stirring and so, annoyed with their secrets, he would feign sleep until whoever it was retreated to the kitchen and the whispering hissed up again like damp green eucalyptus logs burning.

From Careful, He Might Hear You by Sumner Locke Elliott, 1963

Tara Moss, fashion model turned crime novelist, is in Canada to promote her second novel, Split, and is interviewed by Alexandra Gill in the "Globe and Mail".

Moss grew up in Victoria [Canada] with a fascination for all things morbid, which she attributes to an early immersion in Edward Gorey's Gothic books for children. By the age of 10, Moss was writing gruesome Stephen King-inspired stories that cast her classmates as murder victims. "I was a bit strange," she confesses.[Thanks to Confessions of an Idiosyncratic Mind for the link.]

"The Australian" newspaper is reporting that new writer, Kate Morton, is receiving major interest in the manuscript of her novel. "According to her publisher, Allen & Unwin, her novel, The Shifting Fog, has been sold to 11 countries and advances for it and her second novel are approaching $1 million."

Morton's deal is being compared to that received by Chloe Hooper for her novel A Child's Book of True Crime, which was later shortlisted for the 2002 Orange Prize for Fiction.

It is interesting to note that the article in "The Australian" refers to Morton as a first-time novelist and yet also mentions that she has had two previous novels rejected.

Dirt Music by Tim Winton, 2001

(Picador 2001 edition)

Cover image by Gerry Images Australia.

The Age

Shaun Carey has a look at The Weapons Detective: The Inside Story of Australia's Top Weapons Inspector by Rod Barton, and finds it "open-minded, apolitical and free of anger". Yet "does manage to fire some bullets. He concludes that the US, Britain and Australia did go to war on a lie. And like the trained scientist he is, he poses questions about the health of our democracy, not with some fulmination about John Howard but with a raised eyebrow about the pressures that are placed on public servants and military officers who know something about such things as prisoner abuse but are 'discouraged' from coming forward."

The Betrayal of Bindy Mackenzie is Jaclyn Moriarty's third YA novel and it is reviewed this week by Frances Atkinson: "Moriarty's book is satisfying and engaging. Some young-adult authors merely engage in a clever act of ventriloquism, but Moriarty's prose has a recognisable air of authenticity. It reads like a teen soap opera but with feeling."

Jeff Sparrow reviews Cassandra Pybus's history, Black Founders: The Unknown Story of Australia's First Black Settlers and concludes that "white Australia has a black history - and it's more complicated and fascinating than most of us ever knew."

Short notices are given to: Where Fate Beckons: The Life of Jean-Francois de la Perouse by John Dunmore: "You don't have to be especially interested in the 18th-century French explorer to get into ths academic, very readable biography, but it would help."

The Australian

Not a lot here this week with only Kylie Tennant: A Life by Jane Grant getting a review of any sort. This is part of a new series of short biographies commissioned by the National Library of Australia. "Grant focuses admirably on the most interesting feature of Tennant's career, however, which is the unresolved tension between the professional and artistic aspects of her writing life. Tennant was invariably defensive or flippant about her writing, insisting she wrote only to please her father or husband, or to make money (though at times this was significant, given the mental illnesses of her husband and her son). But Grant suggests fear about the limitations of her creative imagination held her back...Tennant clearly was a frustrating novelist, hugely talented but unwilling to allow her work time to evolve."

The Sydney Morning Herald

Bob Wurth's book, Saving Australia: Curtin's Secret peace with Japan is reviewed this week by Tony Stephens. You'll recall that Bob commented on this weblog, a week or so back, correcting some factual errors in Ross Fitzgerald's review of the book in "The Australian". So it will be interesting to see if Stephens has fallen into the same trap or has actually read the whole work. It certainly starts with praise: "Bob Wurth has written an extraordinary book about a remarkable period of history, focusing on the relations between Kawai and John Curtin, the then prime minister, and other prominent Australians, such as High Court judge Owen Dixon." And continues later: "His research and writing is that of a good reporter: the account of Curtin's train trip from Canberra to Melbourne a few days before Pearl Harbour is gripping; the love story involving Kawai and his American secretary sensitively told." But as a review it merely skims the surface of the book without delving into the whys and wherefores. This book is starting to look really interesting.

James Bradley reviews Black Founders: The Unknown Story of Australia's First Black Settlers by Cassandra Pybus, and finds that the author's story of the first dozen black slaves sentenced to transportation is "surprisingly fresh, perhaps not least because its emphasis on the rum-soaked brutality of colonial life is so at odds with the tendency by recent historians to portray the settlement (for all its faults) as something rather more utopian."

Ex-senator John Button reviews Fear and Politics by current parliamentarian Carmen Lawrence. Button always writes well and this review, with a touch of anecdote, a pinch of history and great dollops of insight, is a joy. If Australia ever had a publication like The New York Review of Books, you'd have to ask Button to be one of the resident reviewers of political works. He calls this "a gutsy and thoughtful book".

Nathan Hollier, editor of Overland magazine, takes up the discussion of the Miles Franklin Award in "The Age" this morning. Hollier takes a similar approach to the award as Jane Sullivan and myself, though he does state: "Perhaps Australia does need a new literary prize, for which the novels of all Australian writers can be considered, but it also certainly still needs the Miles Franklin. The short-listed novels for this year's award are all centrally concerned with Australian history, society and culture, and often, as Castro suggested in relation to his own novel, in a very critical way. In the absence of an award with the particular, thematic provisions of the Miles Franklin, publishers - and major publishers in particular - would be much less likely to publish those works specifically concerned with our society and culture."

The winner of the 2006 award will be announced on Thursday, 22nd June.

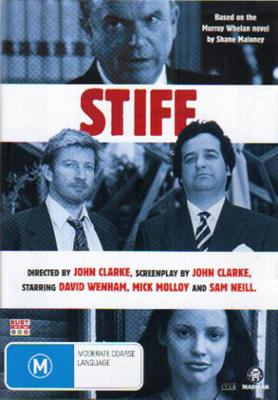

Stiff 2004

Directed by John Clarke

Screenplay by John Clarke from the novel by Shane Maloney

Cast: David Wenham, Mick Malloy, Sam Neill, and Alan Hopgood

"Seasons bloom and seasons wither; dark or bright, they cannot last;"

I suppose, my noble Brereton, you think that patter "fast;"

But it's stale as hash-house "resurrection" remnants of the past.

Let the seasons slide? Of course, sir; 'cos you've got to and they will!

Not the seasons are the matter, but the chances that they kill;

He's a fool who dreams past chances are the present chances still!

Go it, merry, Brerry gallant, go it rattling while you're young,

Tell the girls their kisses bellows-up the love-songs on your tongue,

Tell your mates, and fool yourself, too, that "we never can go bung."

Look around you, Brerry songster, where the friends are of your past;

Men whose gifts of brilliant promise limned a future ne'er outclassed;

Read that future in their present. Don't it make you stand aghast?

Dux, who should have been a Potentate, by future then read clear,

Lurks at corners on the roadway of the daily path you steer,

Tugs your elbow softly, humbly, as he tries to "bite your ear."

Same with Vox and Jus and others, who were leaders in their prime,

And who held, like you, my Brerry, that the present is a chime,

That the flow'rs and girls and rainbows are a merry pantomime.

'Cos their hearts are light and open, opened they their purses, too,

'Cos they whooped the whoop of "Now's-the-time," they paid the reck'ning due,

Let us hope, my Brerry buster, such a fate won't happen you.

"Seasons bloom and season wither!" Yes, but Man has only one

Set of seasons in his lifetime -- Spring and Summer -- then he's done;

Then comes harvesting and winter! Where's his chance of future fun?

If he's grabbed his pile and kept it, shut his ears to woes of peasant;

Made his joys from others' sorrows, shut his eyes to things unpleasant;

Then he may (if glut permit it in the bloated!) "sing the present."

Men don't bloom again when once they start to wither; Winter's blast

Never starts the Spring's soft zephyr in a life once overcast --

And the wrecks -- that's all the Poets -- thus can only "sing the past."

Blood is ichor! marrow's callous! present outlooks make us freeze --

Sing us wine and sing us Women -- time has always room for these;

Let our sinned joys boil to thrill us. Sing the Past; its Memories!

First published in The Bulletin, 15 February 1896

Note: This poem refers to the poem

from last week. "The Dipsomaniac" was a pen-name for Henry C. Cargill.

"The Guardian", and just about everyone else, is reporting that Peter Weir has quit the director's chair on the film adaptation of Shantaram by Gregory David Roberts. Seems he had a difference of opinion, with star Johnny Depp and the film studio, about how to approach the story of the ex-heroin addict, prison escapee and Melbourne author.

Jonathan Stahan (over on his weblog Notes From Coote Street) alerts us to the fact that the Perth-based sf radio show, Faster Than Light, now has a blog, and is podcasting their show. Three programs are now available for download. So far the blog only has postings announcing the availability of the podcasts. Hopefully more will be featured in the future.

The radio program is hosted by Grant Stone and Wolfe Bylsma, and features news and reviews of the sf and fantasy fields in books, film and tv.

It's peculiar where you find Australian books cropping up these days. Now comes the news that Phaic Tan, the bogus travel guide by Santo Cilauro, Tom Gleisner and Rob Sitch (the guys from Working Dog), has been recommended as one of best beach books of the year by "The Village Voice".

[Thanks to The Literary Saloon for the link, though I guess they were looking at the more literary side of the list.]

| Venero Armanno CANDLE LIFE Vintage, 349 pp. Review by Perry Middlemiss |

An unnamed Australian novelist is living in Paris, mourning the death of his lover, and struggling to recapture the rhythm of writing. He spends his waking hours thinking of her, reliving his life with her, and wandering the streets of the city. It's out on the streets that he comes into contact with a Black Cuban-American beggar named Jackson "Sonny" Lee, who gradually insinuates himself into the writer's life, and who eventually leads him to the catacombs under Paris, where the novel's ending is played out. In the meantime, the novelist has a friend die in his artist commune apartment, takes that friend's niece as a lover, gets involved with a mute Russian prostitute and generally has a hard time getting on with his life.

There seems to be a lot of symbols populating this book, and, as indicated by the novel's title Armanno uses the presence of candles throughout the book as a motif indicating life and stability.

My rugged accumulation of mountainous wax is as tall as a table and as wide as a television. When the power goes out, which it does to the point of clockwork madness, all I have to do is find the black stub of a wick in all that gloop and light it with a match. The thing is made of the remnants of hundreds of candles, and there are black wicks by the score. I can choose to light one or a dozen.And later, Sonny tells him:

I took note of that giant candle thing in your room at the commune. I guess that was supposed to be the candle of enlighment. One flame lights the next and the next and the next etcetera. But any good guru will tell you that underneath a candle is always the darkest place of all, so how does that sit with whatever that mountain of congealed wax was supposed to mean?His life's ebbs and flows become defined by his candles and when he is evicted from the commune the giant wax sculpture is destroyed by the cleaners. From that time on his life starts running out of control. He moves in with Lee and oscillates back and forth between his French and Russian lovers, fixated with both in turn, unable to decide where his best options lie.

It is hard not to think that we are being shown a journey here: a journey from the light into the darkness and back out again. Armanno's protagonist follows a path that seems to mirror parts of Joseph Campbell's hero myth-cycle: the journey to Paris as "the call to adventure", the meeting with Sonny as "supernatural aid", his lovers as "the meeting with the goddess" and his journey into Paris's catacombs as the "road of trials" and the trip to the underworld. The narrator has entered a world he does not fully understand and from which he always feels alienated. That, along with the use of symbols and motifs, supports this mythological reading.

The problem is that Campbell's outline is at its dullest when the return from the "otherworld" is denied, when the hero decides to remain behind and not to reveal his new-found knowledge, and it is this path that Armanno appears to have taken with this novel. I say "appears" because the ending of this book is obscure and confused; a drug-enduced blundering though the passageways of the catacombs and the byways of history. I can only assume that the author meant it to be that way. But I've always had trouble with dream and drug sequences - I never think they work effectively.

Armanno has written a complex and, for the most part, compelling novel. There is a lot to admire about his descriptions of the streets of Paris, the interactions between the characters, and the strange and mysterious history of Lee. It's just a pity he couldn't find a satisfactory way to end it.

Matthew Lamb reviews Flag and Nation by Elizabeth Kwan in "The Courier-Mail". "A senior researcher at Parliament House in Canberra, Kwan has produced Flag and Nation, a thorough and much-needed history of the transition from the Union Jack to the Australian national flag we know today (the blue ensign)...The evidence this book presents leaves the impression that no one can argue any longer, through citing 'tradition', that we should keep the current Australian (blue ensign) flag: because no such continuous and inclusive tradition in favour of the Australian flag exists."

In "The Bulletin" this week, Barry Oakley looks at three new debut Australian novels: Poinciana by Jane Turner Goldsmith "...is an impressively assured first novel, as insightful about personal emotions as it is about the political tensions that undercut them"; Grass Dogs by Mark O'Flynn, who "paints Edgar [the main character] with such sure and savage strokes that he is the novel, and the novel is him"; and Billy's Tree by Nicholas Kyriacos which "is told so well you could call this the great Redfern novel. But Kyriacos insists on telling us the stories of

too many others ... and the narrative energies gradually decompress."

Also in "The Bulletin" (just down the page a bit), Anne Susskind reviews Shadow Thief by Melbourne writer Marion May Campbell, whose novel is "is tremendously accomplished, literary and at times compelling, even scintillating. Although many of the topics are common to Australian women's novels - mothers and relationships and sex, often gay - it is about as far as it can get from chick lit, and the tedious, lengthy recounting of detail and dialogue which characterises too much local writing."

In "The Sydney Morning Herald", Erin O'Dwyer interviews Australian author Tegan Bennett Daylight, whose third novel Safety has been gathering a bit of attention lately. "It is 10 years since Bennet Daylight burst onto Sydney's writing scene. In 1996 her first novel, Bombora, was short-listed for the Australian/Vogel Literary Award. In 2002 she was named one of The Sydney Morning Herald's Best Young Australian Novelists, following the publication of What Falls Away."

Johnno by David Malouf, his novel of post-war Brisbane, has been adapted for the stage and will receive its world premiere at this year's Brisbane Arts Festival on July 14th. The adaptation has been written by Sean Mee, directed by Stephen Edwards, and features Sean Mee, Lisa Armytage, Eugene Gilfedder, and Paul Denny.

Cosmos Magazine, which subtitles itself as "The Magazine of Ideas, Science, Society and the Future", also publishes fiction, mostly of the Australian science fiction variety. The latest story is "Empathy" by Chris Lawson. Other stories from back issues are also available. It seems it takes a couple of months after a story is featured in the print edition that it appears on the website. Seems about right.

{Thanks to the Talking Squid weblog for the link.]

Nicholas Shakespeare reviews Tom Keneally's book, The Commonwealth of Thieves, in "The Daily Telegraph" over the weekend. "Australia is lucky to have Keneally. Few writers have a public voice that one wants to follow into the bedroom. He combines Tom Wolfe's expansiveness with the uncorkable energy of Anthony Burgess. At 70, the historian and the novelist are in perfect balance. His work has the integrity of a good floor...It is one of Keneally's virtues in The Commonwealth of Thieves that he gets down and dirty with his characters from their perspective at the time."

Also in the "Telegraph", Diane Cilento's autobography, My Nine Lives is reviewed by Roger Lewis. "Like [Shirley] MacLaine, Cilento was versatile, full of beans, and could be very beautiful when she put her mind to it...Zero Mostel saw her and was hit by a bus."

It must be Australia week in the "Telegraph" as Kate Grenville is interviewed by Helen Brown. "History for a greedy novelist like me is just one more place to pillage. What we're after, of course, is stories, and we know that history is bulging with beauties. Having found them, we then proceed to fiddle with them to make them the way we want them to be, rather than the way they really were. We get it wrong, wilfully and knowingly. But perhaps you could say that the very flagrency of our 'getting it wrong' points to the fact that all stories - even the history 'story' - are made. They have an agenda, even if it's an unconscious one. Perhaps there are many ways to get it right."

In "The Times", the 21st anniversary edition of Germaine Greer's The Female Eunuch is reviewed by Margaret Reynolds. "The need for The Female Eunuch has never gone away. The emphasis, however, is different. In 1970, Greer encouraged women to value their sexuality - today she promotes their right to safe sex or chastity. In 1970, she was writing for middle-class women - today she is more worried about the poor and the dispossessed."

The Boy in the Bush by D.H. Lawrence and M.L. Skinner, 1924

(Macmillan 1980 edition)

Jacket photograph: "Evening When the Quiet East Flushes Faintly at the Sun's Last Look" (detail) by Tom Roberts. Design by Barbara Beckett.

The Age

John Pilger is one of those writer/journalists that you either love or hate - there just doesn't seem to be much room for any other reaction. His latest collection, Freedom Next Time is reviewed by Jeff Sparrow: "...[his] kind of unabashed identification with the poor and dispossesed enrages Pilger's critics but, for my money, it's a welcome change from the instinctive empathy most political reporters offer to the powerful." I must say that I find Pilger's reporting style to be rather refreshing. Even if he appears to be wrong, he's wrong in a manner that gets you thinking. And I'd rather read him that a bunch of other journalists who only seem to re-arrange press releases. As Sparrow puts it: "Yes, the continuing misery in countries that have suffered so much can be depressing, and the campaigning style of Freedom Next Time will not appeal to everyone. Still, if you're dissatisfied with media-lite and its take on the world, Pilger's full-cream, un-homogenised reporting might be just a taste worth acquiring."

Marshall Browne, author of Rendezvous at Kamakura Inn, looks back on the writing of his first published book, City of Masks in 1977. "My strongest memory is of the sense of excitement during the writing, when it seemed the story was coming straight off the Hong Kong streets via the clacking keys of the Olivetti. Those were the days!"

Short notices are given to: On Looking at Looking: The Art and Politics of Ian Burn by Ann Stephen: "This rigorous yet intimate study of one of Australia's early conceptual artists is a refrsshing reminder that there is much more to the history of Australian art than the familiar big names"; Drawing the Crow by Adrian Mitchell: "it is in his re-creations of the moments of his early life where his writing is strongest"; Each Way Bet by Ilsa Evans who "again plays with the notion of opposites, this time using the device of role swapping to tease out the flaws and glories in the respective lives of two sisters."

The Australian

Australian books are thin on the ground in "The Age", as they are in "The Australian" this week. Phil Brown reviews Billy's Tree by Nicholas Kyriacos, a debut novel which revolves around the expulsion of the South Sydney Rabbitohs from the National Rugby League competition in 1999. But he doesn't think it comes together: "As good as it was to see the greatest game of all in a novel, despite being a league tragic I couldn't sustain my interest; everything went on far too long. Perhaps the author might be encouraged to discover his inner novella the next time around."

Jill Rowbotham looks at Noel Preston's Beyond the Boundary examines his own life during the 19 years of Joh Bjelke-Petersen's premiership of Queensland from 1968. "Woven throughout his memories of these and later episodes that occurred as his career as an ethicist took off is a personal story that includes bouts of depression, divorce and battles with cancer. Preston has put great effort into understanding and explaining his life, and in doing so has provided insight into the values and compulsions of his generation."

[Update: the review of John Pilger's book in "The Age" has found its way onto their website.]

|

Wake in Fright 1971

Directed by Ted Kotcheff

Screenplay by Evan Jones from the novel by Kenneth Cook

Cast: Donald Pleasance, Gary Bond, Chips Rafferty, Sylvia Kay and Jack Thompson

Seasons bloom and seasons wither; dark or bright, they cannot last.

Must we try with floods of bitter teas to vivify the past?

Vainly chase the brown and broken blossoms blown along the blast?

Shall we scorn the flowers around us -- red, or blue, or white as snow --

Flowers giving loads of fragrance unto all the winds that blow

Must we hide our eyes and falter: "O, the days of long ago!"

Never stop to look behind you, if the blaze of glory there

Blinds you to the splendour stretching round about and everywhere.

True, the past was pleasant, Lawson, but the present is as fair.

I, too, love the days when heroes, seeking treasure, seaward sped;

Days of Drake, when English sailors followed where their leaders led;

Days when Marlowe trod the glowing clouds, that thundered to his tread.

Even then, though, there were cowards, traitors, swindler, "business men,"

Plot and murder, slave and master, secret sneer, and wounding pen;

And the poets thought the present vile and barren even then.

And their comrades were no better than some modern mates we meet --

Even though they don't go wearing tights and feathers in the street;

And the girls are dear as ever, and their kisses just as sweet.

Sing the present; drop the drivel of the "days evanished," please!

Though you pray until your pants are burst or baggy at the knees,

You can't bid the sun go backward -- no, not even ten degrees.

First published in The Bulletin, 18 January 1896

The 2006 Sydney Writers' Festival is now over but you can relive some of the highlights by watching the videos that BigPond have made available. Featured writers include Jonathan Stroud, Markus Zusak, Neil Gaiman, Edmund White, Audrey Niffenegger, Hari Kunzru, Susan Orlean, David Malouf and Naomi Wolf. If you dig in a bit you can even access video highlights from the 2005 Festival. Access one of the video streams and on the left hand side of the resultant page you will see a list of the BigPond channels available. The link is in there.

| Reviews of The Ballad of Desmond Kale by Roger McDonald. |

[This novel has been shortlisted for the 2006 Miles Franklin award.]

[This novel has been shortlisted for the 2006 Miles Franklin award.]

Description from the publisher's page:

"In the early 1800s, out of the prison society of governors, redcoats, English gaolers, Irish convicts, and the few free settlers of Botany Bay, one had entured much farther inland than a few dozen miles from Sydney into the vast territory claimed, New South Wales. Or so it was believed until the escape of Desmond Kale and the vengeance of his rival, the wildly eccentric parson magistrate Matthew Stanton. THE BALLAD OF DESMOND KALE is Roger McDonald's broad-sweeping novel of the first days of British settlement in Australia. At the centre is Stanton's pursuit of Kale - an Irish political prisoner and a rebelliously brilliant breeder of sheep. The alchemy of wool fascinates, threatens, and transforms when it is discovered that fine wool thrives in New South Wales as nowhere else in in the world, producing veritable gold on sheep's backs. The laying to waste of Spain (Britain's chief supplier of fine wools) at the end of the Napoleonic wars, opens vast new opportunities of supply. THE BALLAD OF DESMOND KALE is both a love story of unusual interest and an epic novel of greed, ambition, conceit, and redemption. The novel is rich in its characterisations and the rawness of its settings, vigour of language, and vividness of personality. The action moves from the early Australian bush to the halls of Westminster, the mills of Yorkshire, the sierras of Spain, the wilds of the Southern Ocean, and returns at last into the far outback for its finale. Once the ballad is sung, ordinary experience is heightened, the world can never be the same again. A brilliant and inspired recreation of the early days of white Australian settlement by one of Australia's finest writers working at the height of his powers."

There don't seem to be any reviews of this novel which react badly to it. All reviewers seem to think it's a pretty impressive piece of work. Peter Pierce in "The Age", can

lead us off as well as anyone, and probably better than most: "McDonald's is a big, ambitious book, a winding tale that takes its due time. There are detours for intriguing subplots - a pregnancy, a feud between half-brothers, a shipwreck, the attempted theft of a map to the fabled inland of the colony, political intrigue over the governing of NSW. There is much detail about the breeding of sheep - the quality of their wool in consequence, the character of the men who are expert in this."

In "Australian Book Review", Michael Williams starts off a bit fixated on the sheep aspect: "How much do you care about sheep? I mean really care about sheep. Because The Ballad of Desmond Kale is up to its woolly neck in them." He does go on from there, which is a blessing: "It's an unusual and inspired variation on the classic Australian colonial novel of hunters for fortune, for identity and for redemption." But Williams does have a few words of caution to impart along with the praise. "This

is a big book that spends a little too long luxuriating in the fun of its grandeurs and at points fails to sustain its narrative drive. The big historical novels that it seems to be emulating have a much clearer sense of focus and of forward momentum. But McDonald does embrace adventure, and at its best, with betrayals and love, ship-wrecks and double-crosses, this is a rollicking good read."

Stella Clarke also considers at the novel in "The Weekend Australian" and is pretty impressed: "Roger McDonald is a riot. This story is balladry of distinction, laid out in prose. He combines a love of intrigue and high adventure with a defiant, lyrical, vigorous way of telling...Here are art and excitement, mixed to magnificent strength. Here are pain and passion, eased through the circumspect medium of a charismatic, old-fashioned style, then springing at you in a gutsy twist of phrase."

Phil

Brown, at "The Brisbane News" probably sums it up for all of us: "This is one of the must-read Australian books of 2005." And it comes as no surprise, to me at least, that I'm still to read it and it's now mid-2006.

In last weekend's "Australian" newspaper, Peter Craven raised the question of whether or not Australia would ever win another Nobel Prize for Literature. It's a reasonable enough parlour game, I've played it myself, so it is always interesting to have a look at the likely, and unlikely, candidates. I say "another" because, as most of us will be aware, Patrick White is Australia's only previous winner of the award, picking up the gong in 1973. The Nobel Prize committee makes it a specific point that a writer's nationality has absolutely no bearing on whether or not they win the prize. Fair enough. But it makes for a pretty boring discussion. The main prize website studiously does not list either the laureates' nationality, nor their language of choice, so I had to consult Wikipedia to get a nationality breakdown. And a pretty interesting one it is too. Top country so far is France, and I wouldn't have picked that. The USA maybe - they run a close second, 13 laureates to 12 - but how many French novelists can you name off the top of your head. Probably no more than four or five who might have been eligible some time in the twentieth century. This is not to denigrate French literature, by no means, it is more an indication of how little we see of it translated and available in far-flung outposts such as Australia. It's just a strange result, is all. Though I must point out that Wikipedia does include Gao Xingjian as French, as he lives there, and I have heard of him. But leaving aside the top countries what about the ones at the other end of the scale that have only won one Literature prize? It makes for interesting reading: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, China, Columbia, Czechoslovakia, Egypt, Finland, Guatemala, Hungary, Iceland, India, Israel, Mexico, Nigeria, Portugal, St. Lucia, Trinidad and Tobago, and Yugoslavia.

Only one each for China and India? Strange. Switzerland has been awarded 2. Needless to say, English is the most awarded language with 26 laureates, followed by French with 13, German with 12, and Spanish with 10. Maybe Australia can point to this statistic as an indicator for why they have only been awarded one prize: Australian works written in English might well get lost in the ruck of the vast numbers of novels, plays and poetry written in that language. Just a thought. But to return to Craven's original article, the list of authors who might be under consideration is an interesting one; mostly for the authors he looks at that you might never consider an even faint possibility. Amongst the usual suspects of Peter Carey, Les Murray, David Malouf, Tom Keneally, Germaine Greer, Clive James, and Shirley Hazzard, you'll also find him talking about Peter Porter, Helen Garner, Robert Hughes, Murray Bail, Tim Winton, Elizabeth Jolley, and Sonya Hartnett; the last of those made my eyebrows head skywards. Craven gradually works his way through this list (although not in this order), praising in turn and dismissing their chances: not enough work produced, not enough variation, too early, aybe too late.

And he comes down to two: Carey and Murray. Peter Carey he deals with first and, while admitting the author may well win it one day, he finds it hard to imagine Carey doing so before such writers as Milan Kundera or John Updike. It's hard to argue with that point. So Craven comes down on the side of Les Murray, "the nation's most famous poet". Of the world's great poets, such as Walcott, Heaney and Brodsky, only Murray has not been awarded the prize. As Craven puts it, of Australian writers "..only Murray would not have his reputation significantly enhanced if he did win it." This year? No, can't see it happening. Writers in English have won three of the past 5 prizes which may have some influence. I know writers in English won three years in a row recently (1991 to 1993) but I also seem to remember some backlash against that succession of wins. So, no, not this year. But I reckon within five years we'll get to see the big fella in a monkey suit. I'd better get reading. Don't want to be caught being as ignorant of Murray as I am of Patrick White when I've had fair warning.

In "The Bulletin", Peter Pierce states his case early, and pretty clearly, in his review of Careless by Deborah Robertson: "Suffer the children is one of the best novels of the year." And later: "With Proudflesh, a prize-winning volume of short stories behind her, Robertson is an experienced writer. Yet little could have prepared her previous readers for the ambition, intelligence and confidence of structural touch of Careless." (You'll need to scroll down to get to the review.)

Graham Williams looks at Voices of War edited by Michael Caulfield, in "The Sydney Morning Herald". The book details interviews with 21 Australians who fought in various wars, culled from over 2000. Williams concludes: "This book should be in every school library in Australia. These people are national heroes."

Zadie Smith has been announced as the winner of the 2006 Orange Prize for Fiction for her novel On Beauty. (The picture on the BBC website doesn't have her looking terribly elated at the news, though she does seem to have quite a grip on the statuette). Smith beat out Australian Carrie Tiffany for the award, who was shortlisted for her novel Everyman's Rules for Scientific Living.

| "Den hiking" |

Recently announced on the Orbit UK website: "Orbit's parent company Hachette Livre is to launch two new SF and Fantasy imprints in the USA and Australia. Orbit, an imprint of the Little, Brown Book Group (formerly Time Warner Book Group), is the UK's leading SF and Fantasy imprint, and the launch of Orbit USA and Orbit Australia will give it a major presence in the three largest English-language markets in the

world."

[Thanks to Jonathan Strahan and the Articulate weblog for details of this.]

Conditions of Faith by Alex Miller, 2000

(Allen and Unwin 2000 edition)

Jacket illustration: Robin M. White/Photonica (woman) and Lorne Resnick/Tony Stone Images (Tunisia)

The Age

The big review this week is of two first novels, a rare event indeed: Juliette Hughes looks at Swallow the Air by Tara June Winch and at Careless by Deborah Robertson. Pity the review isn't on the website, though, knowing how eratic these things are I suspect it might be worthwhile checking back in a day or so.

As has been noted before on this weblog, Winch's manuscript for this book won the David Unaipon Award for Indigenous Writers in 2004. Hughes believes that she has a "voice that will be heard more and more as she grows into the extraordinary talent that has produced Swallow the Air".

"Careless, by Deborah Robertson, is, paradoxically enough written with great care. Each plot part is assiduously interwoven with another: themes of grief, loss, responsibility and betrayal recur as characters do the work that she has set them in slow-moving, hyper-observant present tense."

Both novels would appear to be worth checking out.

Given the amount of interest being generated by Peter Carey's latest novel another view of Australina art might be just the ticket. Which brings us to Voyage and Landfall: The Art of Jan Senbergs by Patrick McCaughey. John Mateer reviews it and finds that: "While having the inevitable limits of the artist's monograph, a literary form that occupies an awkward middle-ground between biography and critical study, McCaughey's correlation of [the associations between style and location] in Senbergs' work is perceptive and useful."

Short notices are given to: His Name in Fire by Catherine Bateson: "In this engaging verse novel, Catherine Bateson takes the emotional life of the young people in her story serious...Bateson's touch is deft"; Pagan's Daughter by Catherine Jinks who "had commercial and critical success with her series of books for older children about Pagan, a medieval Templar squire. Ten years after the publication of the fourth and last book in that series, Pagan's daughter Babylonne makes her first appearance in a book that can stand independently and seems to signal the birth of a new series."

The Australian

Australian books are a bit thin on the ground in "The Australian" this week. We have The Wran Era edited by Troy Bramston, and Saving Australia by Bob Wurth, both explorations of Australian political history and diplomacy.

Neville Wran was an important figure in Australina Labor politics, not least because he was elected to government in NSW in 1976, only five months after Gough Whitlam's Federal government had been sacked by the Governor-General. Mike Steketee finds that "Discounted for the Labor boosterism and a degree of dross, this book provides insights into an absorbing period in politics."

Bob Wurth's book, which is reviewed by Ross Fitzgerald, seems to wander into the realms of fantasy and "goes so far as to suggest that eight days before it happened, Kawai [Japan's first minister to Australia] warned [John] Curtin about the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. He also argues that, between them, Kawai and Curtin, as Opposition leader and then as PM, worked towards a secret agreement between Japan and Australia to keep both countries neutral." Fitzgerald doesn't think he makes his case.

I can't seem to read another online newpaper, or magazine, without coming across a review of Carey's Theft. If his publishers are keeping track of the review clippings then they're doing a pretty good job. It's turning into a hefty volume.

The latest one to come to light (to me at least) is one of the best: a James Wood review in "The London Review of Books". I don't see much point in commenting on this one, I'll just pick a few highlights.

"As he did in his last novel, My Life as a Fake, about the Ern Malley hoax, Carey delights in stripping authorship of authority, and in floating the heretical notion that the reader - or the market - may be the final author of the work."

"Carey likes these intricate, spangly plots, with their outrageous truancies from verisimilitude and their lizard-like velocity; he is one of the most fantastical storytellers in the language, and yet the stories are not unreal, and this is partly why readers can never decide who he is like: is it Dickens, or Joyce, or Kafka, or Faulkner, or Nabokov, or García Márquez, or Rushdie? Two of the realisms that ground these dense fantasies are Carey's ability to animate even minor characters with a flick of novelistic attention, and his great interest in the warped reality of spoken language. One of the great familiar pleasures of his new novel is the way the language recklessly mixes different registers into a vivid democracy, now high and now low, but always interestingly rich.."

"The jovial cynicism of Theft, and its poststructuralist scepticism about the necessary presence of the author in a work of art, seem rather easy achievements for Carey, not least because he dealt with them so nimbly in My Life as a Fake. As in that book, the real subject - Carey's abiding subject, addressed in novel after novel - is the hoax of Australian identity, and its self-tortured relationship with the rest of the world."

In "The New York Times", William Grimes has a look at In Tasmania by Nicholas Shakespeare, but isn't too impressed by what he finds: "If only Mr. Shakespeare, a limp, reticent tour guide, could drop his English reserve, the book might have done justice to the place. Tasmania screams out for lavish, Technicolor physical description. It begs for a writer willing to sink his teeth into the place as if it were a juicy steak. The anemic Mr. Shakespeare specializes in meaningful pauses and cryptic silences. A pastel watercolorist, a stylistic vegetarian, he is inadequate to the task...Mr. Shakespeare should have spent more time chatting with the locals and feasting his eyes on the world around him. Less time spent in the archives, and carefully polishing each of his lapidary sentences, might have served his purpose better."

Scott Westerfeld is another author we've adopted, this time from the US, and his latest novel, Pretties is enthused over by Amanda Craig in "The Times": "Westerfeld has created a gripping thriller about a dystopia founded on ideas of beauty, with all the gadgets, urban planning, moral dilemmas and medical disasters of superior science fiction."

Ali Smith gets into the Theft reviewing act with a piece in the "Daily Telegraph". She appears a little smitten by the novel: "Imagine a cheerful Faulkner, or an even earthier Nabokov. Not possible? Peter Carey is the embodiment of what seems such a literary impossibility, and a writer like no one else in the merry infectiousness, the persuasive relentlessness of his literary energy...A critique of both the art business and the business of love, this is a funny, gorgeous steal of a book."

At the foot of Mt. St. Leonard where in spring the wattles glow,

Where the mountain-ash and messmate 'midst the densest bracken grow,

There's a mountain creek that wanders 'neath the green boughs hanging low,

Where I finished with my mate Dennis in the days of long ago.

With an angler's calm precision "Den" picked out a likely pool,

Where we fed a host of yabbies of a most pugnacious school,

And I soon discovered thereby that the yabbie is no fool

When it comes to robbing fishes in a manner calm and cool.

Down between the lors and shadows we could see the blackfish sweet,

Oh, so juicy and so succulent "Den" said they were to eat,

With some breadcrumbs rolled around them in a manner nice and neat,

Fried in butter (not with dripping) they would be a perfect treat.

All this talk while we were beaten in a cunning sort of style,

Outmanoeuvred and outgeneralled by the strategy and guile

Of the calm Toolangi yabbies who consumed our bait the while

Blackfish couldn't get a look-in though queued up in single file.

So we dined that night more simply on a Dennis omelette,

And the poet swore, by crikey, they were his best as yet,

And I did not mention yabbies lest he'd break out in a sweat,

Nor the blackfish, nor the butter, nor the breadcrumbs, don't forget.

First published in The Bulletin, 7 October 1953

| Brian Castro THE GARDEN BOOK Giramondo, 316 pp. Review by Perry Middlemiss |

[This novel has been shortlisted for the 2006 Miles Franklin Award.]

Let's get one thing straight right off the bat: Brian Castro can write. Unfortunately I have a feeling this is akin to reviewing a play and commenting only on the sets and staging. It amounts to "damning with faint praise", which isn't what I intended, but which does provide some forewarning of my divided opinions of the novel.

The Garden Book tells the story of Swan Hay (born Shuang He), the daughter of a country school-teacher of Chinese ancestry, of her husband Darcy Damon, and of the American aviator-architect Jasper Zenlin, who becomes the love of her life. The main body of the book is set in the Dandenong Ranges outside Melbourne in the period leading up to and during World War II. The novel is framed within the attempts of Norman Shih, a rare-book librarian, to piece together the story of the three from an old diary and a job lot of "Letters, postcards, ledgers, old paperbacks." The story is presented in a series of accounts around each of the characters in turn, in the order in which they enter the plot: Darcy, Swan, Jasper and then Shih to round it out, to tie up the final knots.

That arrangement is reasonable enough. The execution leaves something to be desired, however. Darcy's story is told in the first person as it appears that we are reading from his diary, though this is not made totally clear. He's a strong character, big in body and therefore deemed to be rather slow, though he does actually possess a powerful intellect which slowly manifests itself through the book. Castro is spot-on with his voice and the following quote could have been matched by just about anything from his part of the book.

I only remember my father as a smell. Pipe-bowl shag. His heavy goanna hand reaching round the back of my neck. His boots, ten sizes too big for me, stand empty on the back patio where my pet echidna shuffles back and forth, chiselling at the posts for ants. There's my mother through the kitchen window, boiling up plums for jam. her face is pale; she's sick again. The house is an arsenal of guns and axes. The only family portrait I have. Fleeting happiness tinged with remorse. At least everyone's got clean shirts.The only difficulty with Darcy's story is that Shih keeps intruding without warning; adding to Darcy's story by filling in the gaps between diary entries. How he is able to write in such an omniscient narrative voice is difficult to determine, and starts to grate after a while. This effect is probably accentuated by the fact that it takes a while to work out that it is Shih speaking. I kept wondering why the point of view kept changing and had to keep checking back in Darcy's section to work out what was going it. I found it quite disconcerting.

By the time I got to Swan's part of the book, I'd started to figure out the technique and wasn't so put off by it. That is, until Castro changes his methodology again and starts to interleave entries by Darcy and Swan, each headed by their name. At least he forewarns us this time:

Outside my office window, a jet creases the sky with condensation trails while Swan's entry for this day fades into bluish patches of ink. In the margin near the spine she's teasingly pressed a small blank leaf. The gaps in these notes invite my participation. What does Darcy say?At this point in the book I was starting to think that it was going to be an exercise in technique and structure over plot and story, but things start to pick up when Jasper enters the scene. Darcy and Swan are married and Darcy has fortuitously acquired a degree of wealth which enables him to engage Jasper the architect to build a house and a series of outbuildings for them. The arrival of Jasper completes the triangle, Swan is smitten by his other-worldliness, his charisma and the chance he offers for an escape from a country that barely acknowledges her existence. But the outbreak of war scuttles any hopes she might have of utilising her new-found celebrity as a poet and it all ends as we might expect of such an arrangement, at such a time.

Castro himself has acknowledged that a number of large publishers refused to accept this book in its current form, demanding more changes to the structure and content than he was willing to permit. As a consequence he has taken up with the small Sydney publishing house Giramondo. I believe Castro was right in sticking to his guns and I can see why this novel had difficulty in finding a place. The trouble is I think he should also have taken some notice of the original criticisms. It might have made the book more approachable.

In the end I believe the author has produced a magnificent failure. As I said at the start, the man can write. For days after finishing this book I was still thinking about it, trying to work out what he was up to and how he hoped to achieve it. He got there in the end, but the route he took wandered down paths that left this reader feeling more than a little lost a lot of the time.

[Update: I originally identified this book's publisher, Giramondo, as being Melbourne based. It is, in fact, located in Sydney.]

Justine Larbalestier is interviewed by Jason Nahrung in "The Courier-Mail" about the publication of Daughters of Earth: Feminist Science Fiction in the Twentieth Century , an anthology she has edited. The book contains 11 classic stories by women writers from the 20th century, accompanied by critical essays about each story. "A chance, Larbalestier says, to give credit where it has largely been unpaid in the past, as well as making some hard-to-find stories accessible once again."

The interview also touches on her own writing with Magic Lessons, the sequel to Magic or Madness, being published in Australia in September. A third book will follow.