| James Bradley THE RESURRECTIONIST Picador, 333 pp. Review by Perry Middlemiss |

"Don't judge a book by its cover" the old adage runs. Yet we all fall victim to it. We're conditioned to it, and publishers and marketers expect it of us. Mostly this is not such a bad thing, at least as far as books are concerned. The cover art, the blurb on the back, the author photo, the typeface, the paper quality, even the size of the bloody thing, all merge together to produce a first impression in our minds. So it's of special interest when a book leads you one way, and then swerves another. Such a book is The Resurrectionist, the new and third novel by James Bradley.

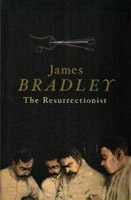

The cover of the Australian edition is striking, in that it is mostly black. Surely not a great colour to catch the eye, you think. And what's that thing above the author's name and title? It looks rather sinister. Then there are the figures at the bottom, all intently studying something "off-cover". You're being led somewhere, that much at least is obvious. The book has the look and feel, the heft, of a literary novel, and yet, there's this thing about it - a thing that leads you to expect a horror novel. And in some ways, that's what you get. But in many, many other ways you get far more than that. You get a literary novel that uses the techniques and traditions of the gothic genre, and that twists and stretches them into patterns rarely seen.

The novel is told in first-person narration by Gabriel Swift, an orphan in 1820s England, who is sent to London to study with Edwin Poll, one of the great anatomists of the time. Gabriel's role is to help prepare for Poll's lectures - in other words, to wash and clean and lay out the bodies for dissection. At that time only the corpses of the executed could be used in such a way, and, of course, there was a shortage. So Poll's house is drawn into the commerce in human bodies, dealing with the resurrectionists, the grave-robbers of the novel's title. This illegal trade has a corrupting influence on all who partake of it and Gabriel is gradually drawn deeper and deeper into the depravity of the exhumation and theft of the world around him. He falls, both professionally and personally, into a pit of his own making and from which there appears no escape.

Over three-quarters of the way through the novel, the locale changes from London in the 1820s to the colony of New South Wales in 1836: an abrupt shift from the dark and grime of England to the bright light and clear air of the Australian continent. At first this jump is rather unsettling: we have a new location, a new time and, at first, what seems like a new protagonist and narrator. But Bradley has unsettled us for a particular reason. One that at first is not at all obvious.

Bradley's choice of his protagonist's name is an apt and significant one. The angel Gabriel of myth is the Archangel of humanity, resurrection, death and hope. A heavy load if ever there was one. And Bradley uses his narrator to carry the similar weight of his novel. In other words, the book lives or dies on how the reader takes to his narrator. At the beginning of the novel Gabriel has our full sympathy. He is a child without prospects, without hope, who is taken into a world where he might well advance to a position that he might never have dreamed of. He begins as a boy among men, an innocent among the corrupt and as the novel progresses we see him slowly change, losing his boyishness and his sense of innocence. He becomes devious both in his personal and professional habits and his final fall is swift and abrupt. He is expelled from the company of Edwin Poll's household and finds himself without hope and at the mercy of the resurrectionists. He reaches a point where drug addiction and murder are commonplace occurrences, passing almost without regret, and yet he still has further to go. At the last his descent into the depths is complete when he betrays his new companions and he finds himself trapped in a metaphorical Hell.

Throughout the book there is a growing sense of foreboding. The change in Gabriel is subtle and measured and you find as a reader slowly becoming unsure of whether to trust him as a narrator. Is he giving us a true account of his life, or only a disordered narrow view of it? It's this realisation that Gabriel probably knows more than he is telling us, that he knows something awful is about to happen that builds the suspense within the plot. We almost can't bear to look, but, at the same time, can't bear not to. This is a classic horror technique; one that usually ends with the "monster" appearing and blood spurting every which way. But the best horror works don't show us the "monster", we only get glimpses of it out of the corner of our eye, a flash as it crosses a doorway. We know it's there, we just can't get to see it full in the face.

So it is with Gabriel's demons - they sneak up on us, corner us in the graveyard, and, just as we think we understand what is happening we cut to the light. We suddenly find ourselves in a place totally different from the one we just left. Handled well it's a wonderful technique, jarring and disorientating. Without the initial spadework, however, it can be a mess, it doesn't work and we don't believe it. In The Resurrectionist Bradley would have struggled to have achieved a better result. The transition from the dark into the light, from claustrophobic London to "the sunlit plains extended", is complete and totally satisfying. Just like the rest of the novel.

Early on in the book, Edwin Poll, Gabriel's master, addresses a lecture-hall of students, and delivers what might be considered his raison d'etre: 'We are men of science, gentlemen, students of nature. It is our purpose to tear down the veil of superstition, to pierce the very fabric of our living being and elucidate the nature of the force which animates these shells we call our bodies. And we will find it here, in this cold flesh. For these tissues we will divine the shadow of that force which drove the fuse within, which set his heart to flicker and beat. Call it a soul if you wish, yet I promise you it shall prove no more and no less mysterious that this magnet's power to bend these filings to its will.'

In many ways this creed might also apply to Bradley's role as the author of this work. One that he fulfils admirably. Read this book.