I was led to the New York Public Radio site for an interview with Markus Zusak and found that Tim Flannery is there as well. Both interviews are available as downloadable podcasts.

[Thanks to Judith Ridge at The Misrule Blog for the link.]

I was led to the New York Public Radio site for an interview with Markus Zusak and found that Tim Flannery is there as well. Both interviews are available as downloadable podcasts.

[Thanks to Judith Ridge at The Misrule Blog for the link.]

As his book on climate change is published in the US, Tim Flannery is interviewed in Wired magazine.

The comments by readers of this interview are interesting. Most set out to disagree with Flannery or to push another barrow. The best of them: "Flannery's words would carry a lot more weight if he weren't trying to sell a book. Nothing sells books like good 'ole fear."

The trouble is, mate, you wouldn't listen if he didn't have a book out, 'cos then you'd just say he didn't have any evidence to back up his arguments. He can't win either way, and you're stuck in a very deep rut.

[Thanks to the folks at mediabristro GalleyCat for the link.]

The 3rd annual Emerging Writers' Festival will be held in the Melbourne Town Hall from April 7-9. The website describes it as: "The festival will promote, network and engage with a range of Australia's most exciting writers. It will be a celebration and investigation of writers of all ages and in all literary forms: from comics to screenwriting, journalism to activism, poetry to hip hop, and novels to plays. And in 2006 the EWF will feature Indigenous writers from around Australia. "Over three days there will be workshops, panels, performances, magazine launches, films, lectures, and a party to re-define your ideas of literary performance! All this for only $15/$25 for a weekend pass, or $10/$15 for a day pass." There is a program and registration form on the site [PDF file].

Over at The Australian Reader website Kate Smith is publishing a crime novella online in serialised form. The current episode is number 6, with the previous entries all available. There will be 13 episodes in all with a new one being published each Friday.

The novella, Wishbone Street, is illustrated by Ashley J Higgs and the author describes it as a story that "combines elements of the supernatural, crime, romance, humour and drama."

| Reviews of Everyman's Rules for Scientific Living by Carrie Tiffany. |

[This novel has been longlisted for the 2006 Miles Franklin award, longlisted for the 2006 Orange Prize for Fiction and was shortlisted for the Best First Book Award for the South East Asia and South Pacific region of the 2006 Commonwealth Writers' Prize.]

Description: "It is 1934, the Great War is long over and the next is yet to come. It is a brief time of optimism and advancement.

"Billowing dust and information, the government 'Better Farming Train' slides through the wheat fields and small towns of Australia, bringing city experts and advice to those already living on the land. The train is on a crusade to persuade the country that science holds the answers and that productivity is patriotic.

"Amongst the swaying cars full of cows, pigs and wheat, an unlikely seduction occurs between Robert Pettergree, a man with an unusual taste for soil, and Jean Finnegan, a talented young seamstress with a hunger for knowledge. In an atmosphere of heady scientific idealism they settle in the impoverished Mallee with the ambition of proving that science can transform the land.

"With failing crops and the threat of a new World War looming, Robert and Jean are forced to confront each other, the community they have destroyed, and the impact of progress on an ancient and fragile landscape.

"Erotically charged, and shot through with humour and a quiet wisdom, this haunting first novel evokes the Australian landscape in all its stark beauty and vividly captures the hope and disappointment of an era."

In "The Age", Judith Armstrong initially thinks the book may have something to hide: "You can't see a title such as this without suspecting its author of playing games. What lies behind the joke? Carrie Tiffany, who regards her own name as 'ridiculously flaky', is a first-time novelist who has already received some excellent publicity." But she soon comes to realise that the book is far more than just a funny title, and that it is "a

highly accomplished, adroit and funny-serious novel, which, unlike a Mallee farm, works almost perfectly."

The general consenus of opinion amongst reviewers of this novel is that it is an impressive debut. At AussieReviews, Sally Murphy found that "Everyman's Rules for Scientific Living is a powerfully haunting novel. Set in the period between the two worlds, in a community struggling through the depression and drought, this is a gripping first novel from a new Australian talent."

A claim that was echoed by Publisher's Weekly in the US, which called it a "rich and knowing debut novel." And which then went on to state: "Acclaimed Australian story writer Tiffany writes in a deceptively simple style, notable for its craft and heartbreaking clarity; that as well as her unusual yet utterly believable period

characters make for a stunning debut."

William Elliott's manuscript, The Pilo Family Circus, has been named the inaugural winner of the ABC Fiction Award. The award brings with it a prize of $10,000 and publication by ABC Books. Elliott's work was chosen from 900 entries, and a short-list of 25. The 2007 ABC Fiction Award is now open and entries must be received by May 30 2006.

[Thanks to Ron at Mountain Murmurs for the link.]

There was another mode of composition, very much slower and more painful, in which she strove to capture the essence of certain events, real or imagined, as precisely as she could, and here she felt she might one day acquire a very different sort of facility, if only she could stumble upon some great conception, something that would absolutely distinguish her work from that of hundreds of authors whose novels crammed the circulating libraries and bookstalls and joustled one another for notice in the pages of the reviews. At least half a dozen times she had launched herself with high hopes into "Chapter One", and felt her tale to be well under way, only to see a darkness fall across the page, blighting her carefully wrought sentences until her characters lay down, as it were, at the side of the road and simply refused to go on. And then persons from Porlock, usually in the form of her mother, would call just as she saw her way out of the difficulty. There were certain pages, composed almost as if from dictation, with which she was entirely satisfied, but they seemed like the work of another person altogether, and remained in any case unfinished. No; the life of an author was certainly not an

easy one.

From The Ghost Writer by John Harwood, pp257-258

------EXTENDED

BODY:

Joseph Furphy (1843 - 1912)

Unemployed at last!

Scientifically, such a contingency can never have befallen of itself. According to one theory of the Universe, the momentum of Original Impress has been tending toward this far-off, divine event ever since a scrap of fire-mist flew from the solar centre to form our planet. Not this event alone, of course; but every occurrence, past and present, from the fall of captured Troy to the fall of a captured insect. According to another theory, I hold an independent diploma as one of the architects of our Social System, with a commission to use my own judgment, and take my own risks, like any other unit of humanity. This theory, unlike the first, entails frequent hitches and cross-purposes; and to some malign operation of these I should owe my present holiday.

Orthodoxly, we are reduced to one assumption: namely, that my indomitable old Adversary has suddenly called to mind Dr. Watts's friendly hint respecting the easy enlistment of idle hands. Good. If either of the first two hypotheses be correct, my enforced furlough tacitly conveys the responsibility of extending a ray of information, however narrow and feeble, across the path of such fellow-pilgrims as have led lives more sedentary than my own -- particularly as I have enough money to frank myself in a frugal way for some weeks, as well as to purchase the few requisites of authorship.

From Such is Life by Tom Collins (Joseph Furphy), 1903

Along with being a damn good weblog Bookslut also publishes an online monthly magazine, and this month their resident sf/fantasy reviewer takes a look at Passarola Rising by Azhar Abidi.

We can argue till we're blue in the face as to whether or not the novel falls into the fantasy category and the reviewer, Colleen Mondor, even acknowledges the problem: "Passarola Rising might seem more like a historical novel or mainstream adventure story, but at its heart it is about an amazing flying machine. The fact that the man who designed this craft was real only makes it that much more wonderful and certainly a title that any fan of Jules Verne (or H.G. Wells) must certainly grab a copy of." And then goes on to say: "Passarola Rising is an old fashioned fantasy, one that embraces the fantastic elements posed by the early 18th century."

Which pretty much allows it to be read anyway you want. And a good thing too.

Oscar and Lucinda by Peter Carey, 1988

(University of Queensland Press 1988 edition)

Cover illustration by Gregory Rogers and Pierre Le Tan

This novel won the 1988 Booker Prize and the 1988 Miles Franklin Award

Marshall Browne continues to get exposure for his new novel, Rendezvous at Kamakura Inn, which is reviewed in "The Age" by Jeff Glorfeld. This is Browne's first novel in a new series featuring Inspector Hideo Aoki, of the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department's Criminal Investigation Bureau. I'm not sure that Glorfeld is overly convinced by the end result: "As with kabuki, Browne writes in a strangely stilted style, as if he has been translated awkwardly from another language. As if in a ritualistic theatre performance, Aoki's inner narration continually loops back over his thoughts, his moral turmoil. It isn't a big book, in this sealed-off stage Browne has set, but by moving slowly, examining every action and reaction over and over again, it takes on the feel of an epic. In a Japanese way, it becomes an article of duty to see the story through to its conclusion." Though he does then go on to conclude: "Readers might throw it down in frustration, but they will probably pick it up again. It can get to you like that, and rewards those who do their duty and see it through to the end." So, it's rewarding but hard work? Can't see a problem with that.

I'd prefer it if reviewers didn't equivocate: don't extrapolate on what some readers might do, state clearly what you thought of it and let readers make up their own minds. I take statements such as "Readers might throw it down in frustration" as a direct challenge, but I'm contrary like that.

The Australian continent and fire have had an intimate relationship ever since the land was first visited however many thousands of years ago. It's a strange mixture of love and hate. Stephen Pyne's new book, The Still-Burning Bush, examines the role that fire has played in the life of this country, which, as Simon Caterson notes, resonates beyond these shores. "The scientific and political importance of fire in Australia is matched by its cultural significance...Australians also have a habit of naming and commemorating fires - Ash Wednesday is an obvious example - which is not replicated elsewhere. For all the death and destruction caused by fire every year, the intense interest in these events is a sign that, like war and sport, fire defines us as a nation." This is a sequel to Pyne's early book, Burning Bush, his history of Australian fire up to the 1980s.

Shotr notices are given to: Aristotle's Nostril by Morris Gleitzman: "Parents and librarians around the nation worship Gleitzman for seducing their children to the world of words and books. And they trust him, for alongside the humour he is consistently compassionate and persistently optimistic"; The Mermaid Tree by Robert Tiley, an "accessible, entertaining study" of the exploration of Australia after the battle of Waterloo; and Venom by Dorothy Horsfield, who "has an acute eye for the way people misunderstand one another. But, just as her characters invent each other, they can equally have moments of insight."

Over in "The Australian", Ross Fitzgerald looks at autobiographies by two former judges who were also both ex-communists: In Off the Red by Ken Marks, and Comrade Roberts: Recollections of a Trotskyite by Kenneth Gee. And a mixed bag he finds them as well.

In addition, Debra Adelaide reviews Drink Me by Skye Rogers, which falls directly into the "Harrowing Memoir" genre, and Christopher Bantick is impressed with Patrice Newell's memoir of life on the land, Ten Thousand Acres: A Love Story.

Jason Nahrung considers Scott Westerfeld's new young adult novel, Peeps, in "The Courier-Mail", and finds that "the ride is fun and at times spooky and beautifully sketched". On the other hand, Leisa Scott did not like Carry Me Down by M.J. Hyland at all, throwing the book down in disgust, before picking it up again to get stuck into it. An uncommon review in Australian newspapers.

It's good to see that the book webpages of Brisbane's "Courier-Mail" have been given a decent overhaul. The previous version hardly had any literary content at all. Chief amongst the new offerings is Suzanna Clarke's piece on the standing of the Miles Franklin Award within the Australian literary community: "Always a Story".

I was certainly pleased to see Alex Miller making a point I heartily endorse: "Winning the Miles Franklin is the only thing that gets you out of the book pages and into the news pages. "You get fabulous publicity, but the response by the bookshops is crap. When the Booker comes out, the shortlisted books are in shop windows for weeks. That doesn't happen with the Miles Franklin." And, to be frank, I can't see why not. The sales of last year's winner, The White Earth, had practically dried to a trickle before

McGann's win. After that it went gangbusters, pushing up towards 40,000 copies. Surely something to be learned there.

I've mentioned Tim Flannery's The Weather Makers here a few times over the past few weeks, which seems only fair as a) it's an important book, and b) I'm reading it. (Note: the second doesn't necessarily follow the first, but on this occasion I'll run with it.)

Now comes the news from "The Telegraph" that there are some changes with the book's cover between the UK and US editions. The UK edition - which is the one I have - features a certain Bill Bryson blurbing: "It would be hard to imagine a better or more important book." Fair enough, he's written that big science book recently - the title escapes me - and he's pretty popular in the UK. It seems, however, that the book's US publishers have opted for British PM Tony Blair in preference. He states: "The Weather Makers provides insights not only into the history, the science and politics of climate change, but also the actions people can take now that will make a difference". "The Telegraph" then goes on to explain: "Mr Blair may not be as popular as Mr Bryson in England but the Americans certainly know an expert on hot air when they see one."

Luckily Mr Blair was here in Melbourne last night for the closing ceremony of the Commonwealth Games so he won't notice this little joke at his expense. My visiting English friends will, however, blow hot coffee out their nostrils when they read this.

Would you like to change with Clancy -- go a-droving? tell us true,

For we rather think that Clancy would be glad to change with you,

And be something in the city; but 'twould give your muse a shock

To be losing time and money thro' the foot-rot in the flock,

And you wouldn't mind the beauties underneath the starry dome

If you had a wife and children and a lot of bills at home.

Did you ever guard the cattle when the night was inky-black,

And it rained, and icy water trickled gently down your back

Till your saddle-weary backbone fell a-aching to the roots

And you almost felt the croaking of the bull-frog in your boots --

Sit and shiver in the saddle, curse the restless stock and cough

Till a squatter's irate dummy cantered up to warn you off?

Did you fight the drought and "pleuro" when the "seasons" were asleep --

Falling she-oaks all the morning for a flock of starving sheep;

Drinking mud instead of water -- climbing trees and lopping boughs

For the broken-hearted bullocks and the dry and dusty cows?

Do you think the bush was better in the "good old droving days,"

When the squatter ruled supremely as the king of western ways,

When you got a slip of paper for the little you could earn,

But were forced to take provisions from the station in return --

When you couldn't keep a chicken at your humpy on the run,

For the squatter wouldn't let you -- and your work was never done:

When you had to leave the missus in a lonely hut forlorn

While you "rose up Willy Riley," in the days ere you were born?

Ah! we read about the drovers and the shearers and the like

Till we wonder why such happy and romantic fellows "strike."

Don't you fancy that the poets better give the bush a rest

Ere they raise a just rebellion in the over-written West?

Where the simple-minded bushman get a meal and bed and rum

Just by riding round reporting phantom flocks that never come;

Where the scalper -- never troubled by the "war-whoop of the push" --

Has a quiet little billet -- breeding rabbits in the bush;

Where the idle shanty-keeper never fails to make a "draw,"

And the dummy gets his tucker thro' provisions in the law;

Where the labour-agitator -- when the shearers rise in might

Makes his money sacrificing all his substance for the right;

Where the squatter makes his fortune, and the seasons "rise" and "fall,"

And the poor and honest bushman has to suffer for it all,

Where the drovers and the shearers and the bushmen and the rest

Never reach the Eldorado of the poets of the West.

And you think the bush is purer and that life is better there,

But it doesn't seem to pay you like the "squalid street and square,"

Pray inform us, "Mr. Banjo," where you read, in prose or verse,

Of the awful "city urchin" who would greet you with a curse.

There are golden hearts in gutters, tho' their owners lack the fat,

And we'll back a teamster's offspring to outswear a city brat;

Do you think we're never jolly where the trams and 'busses rage?

Did you hear the "gods" in chorus when "Ri-tooral" held the stage?

Did you catch a ring of sorrow in the city urchin's voice

When he yelled for "Billy Elton," when he thumped the floor for Royce?

Do the bushmen, down on pleasure, miss the everlasting stars

When they drink and flirt and so on in the glow of private bars?

What care you if fallen women "flaunt?" God help 'em -- let 'em fluant,

And the seamstress seems to haunt you -- to what purpose does she haunt?

You've a down on "trams and busses," or the "roar" of 'em, you said,

And the "filthy, dirty attic," where you never toiled for bread.

(And about that self-same attic, tell us, Banjo, where you've been?

For the struggling needlewoman mostly keeps her attic clean.)

But you'll find it very jolly with the cuff-and-collar push,

And the city seems to suit you, while you rave about the bush.

P.S. --

You'll admit that "up-the-country," more especially in drought,

Isn't quite the Eldorado that the poets rave about,

Yet at times we long to gallop where the reckless bushman rides

In the wake of startled brumbies that are flying for their hides;

Long to feel the saddle tremble once again between our knees

And to hear the stockwhips rattle just like rifles in the trees!

Long to feel the bridle-leather tugging strongly in the hand

And to feel once more a little like a "native of the land."

And the ring of bitter feeling in the jingling of our rhymes

Isn't suited to the country nor the spirit of the times.

Let's us go together droving and returning, if we live,

Try to understand each other while we liquor up the "div."

First published in The Bulletin, 6 August 1892

Bulletin debate poem #4

In "The Australian" last weekend Rosemary Neill wrote a long article titled "Lits Out", or elsewhere titled "Who is Killing the Great Books of Australia?" I meant to link to it earlier in the week, and wanted to make some comments on it. I just couldn't think of much to go on with. I'm not sure that I still can, yet I think it does need to be mentioned and discussed.

Neill's basic premise is that Australian literary fiction is in a very sick state indeed. It isn't dead, it's just not very well. Sales are down in numbers and value and if the current trends continue then it's probably going to slowly fade out of existence.

Her main argument is based on the number of non-genre Australian novels published each year which has fallen from 60 in 1996 to 32 in 2004. And by any stretch this isn't good. One part of the problem seems to lie with the current crop of major Australian publishers, who are all, bar Allen & Unwin, majority owned by non-Australian companies. Current publishing set-up costs mean that a major publishing house has to print, and sell, at least 3000 copies. That doesn't sound like a lot but Shona Martyn, publishing director at HarperCollins, says that a lot of well-known, respected writers sell under 1000 copies of their novels in this country. The finances just don't add up and publishing at those numbers just isn't feasible. Yet you can't blame the publishers for not publishing books at a loss. They are in the business of making money for their shareholders. They aren't a charity and shouldn't be expected to act like one. Martyn also goes on to say that a book only has a window of approximately four weeks to find a niche in the market. After that the focus of the metropolitan newspapers and magazines has moved on, and all that is left is the round of state and national literary awards. It's not looking good.

There is a ray of hope in all this, however. Small publishers such as Giramondo can make ends meet with print-runs about half those required by the big publishers. The trouble is, their resources are limited and they can't take on the whole field.

It's possible to come up with a long list of reasons why this state of affairs has come about: the marketing is ill-conceived or non-existent; the publishers don't understand the market and are publishing the wrong books; readers just aren't interested in fiction any more, let alone Australian fiction. And a case can be made for all of these. You have to add in the general societal changes involving new forms of media, greater availabilty of those forms, and the subsequent lowering of the attention spans of media consumers. I don't think there is any one reason for the fall in sales, all of those listed play a part, but not the total.

I don't work in the industry and don't have a "wonder cure" for the ills of the Australian publishing industry. I don't believe anyone has. Maybe it lies in the unearthing of a major new writing talent, the emergence of an energetic and courageous publisher, government intervention, or the introdutcon of innovative new publishing forms that are cheaper and more easily accessible.

In some ways the current state of Australian literary fiction mirrors the current problems with our male swimmers at the Commonwealth Games: what once was great has now been seen to rely too heavily on one or two heroic performers who are currently missing through injury. In the next six to twelve months I suspect major initiatives will be put in place to correct this sporting "deficiency". If only the same sort of effort could be put into the literary field we might not be having this conversation again in 12 months' time. In the meantime, don't hold your breath in hope or expectation that the Federal Government will step in to save the day. You're going to be severely disappointed.

The nominations for the 2006 Hugo and Campbell Awards have been released. Congratulations, and good luck, to Margo Lanagan, nominated in the Best Short Story category for "Singing My Sister Down", and to K.J. Bishop, nominated for the John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer of 2004 or 2005.

The Hugo Awards are the readers' choice awards in the science fiction and fantasy fields, and are voted on by members of the year's sf Worldcon (in Los Angeles this year from 23-27 August). You have to be a member (either supporting or attending) to vote. Details of the convention are available at their website. There will be a fair contingent of Australians in LA this year, including yours truly, as we are ramping up our bid for the 2010 Worldcon to be held in Melbourne. We'll be running two bidding parties during the convention and will have a table staffed with volunteers at other times to answer any questions. Further details will be released as things are finalised. If you're there stop by and say hello.

My home laptop screen died last night so updates will be a little curtailed over the coming week or so as I attempt to get that fixed. The bloke in the repair shop said it could be anything from a loose connection between the motherboard and the screen to a blown video-card on the motherboard. I'm hoping for the former and expecting the latter.

I'm also away for the next three days, out of internet contact and probably barely in mobile phone range. I'm shepherding some English friends round some wineries in Northern Victoria. Probably wouldn't be able to post here even if I wanted to.

I'm hopeful of being back in business sometime next week. In the meantime some regulars, like the Saturday poem, will appear off-schedule.

The 2006 Sydney Writers' Festival runs from 22-28 May. No program or guest list has been released as yet, but Neil Gaiman has let slip that he'll be there. [It's a few paragraphs down.]

Judith Wright (1915 - 2000)

Beside his heavy-shouldered team,

thirsty with drought and chilled with rain,

he weathered all the striding years

till they ran widdershins in his brain:

Till the long solitary tracks

etched deeper with each lurching load

were populous before his eyes,

and fiends and angels used his road.

All the straining journey grew

a mad apocalyptic dream,

and he old Moses, and the slaves

his suffering and stubborn team.

Then in his evening camp beneath

the half-light pillars of the trees

he filled the steepled cone of night

with shouted prayers and prophecies.

While past the campfire's crimson ring

the star-struck darkness cupped him round,

and centuries of cattlebells

rang with their sweet uneasy sound.

Grass is across the waggon-tracks,

and plough strikes bone across the grass,

and vineyards cover all the slopes

where the dead teams were used to pass.

O vine, grow close upon that bone

and hold it with your rooted hand.

The prophet Moses feeds the grape,

and fruitful is the Promised Land.

Bullocky by Judith Wright, 1944

Ron Hogan, of the mediabistro GalleyCat weblog, went along to the Books of Wonder book-signing of Markus Zusak, Justine Larbalestier and Scott Westerfeld last Saturday in New York. Ron has posted some photos from the signing as well as a link to Zusak's "Good Morning America" appearance that I mentioned the other day. Check it out. It's pretty good, and runs about 5 minutes.

Eucalyptus by Murray Bail, 1998

(Text Publishing 1998 edition)

Cover photograph by Bill Henson from an untitled series

This novel won the 1999 Miles Franklin Award

Sandy McCutcheon, radio broadcaster for the ABC's "Australia Talks Back" and "Australia Talks Books" programs, is also well-known as both a playwright and author. It is his latest novel, Black Widow, which is reviewed in this weekend's "The Age" by Sue Turnbull. The novel tracks a survivor of the Beslan school siege in 2004 who joins up with five other female survivors to kidnap the four adult children of the Chechyan terrorists who were involved in the original siege. The reviewer finds some interest in the book: "In Black Widow, McCutcheon takes political events of the recent past and gives them an immediate human dimension. The fact that his focus is primarily on the women and children caught up in a war about power is understandable and worthy. The book evokes a strong sense of moral outrage and compassion." But finds that the novel may, in the end, not qute live up to its promise: "... could not help but wonder if in opting for the cliche-ridden and at times downright mawkish voice of [the protagonist], McCutcheon, the playwright and master of many potential voices, might have sold himself a tad short."

Other than this novel, short notices are given to The Book of Everything by Guus Kuijer: "This beautiful little novel is a shimmering prism. Simply but elegantly formed, it throws out complex patterns of emotion and thought, dark and light"; and Devotion by Ffion Murphy: "First-time novelist Ffion Murphy has chosen an unusual topic - severe postnatal depression - to explore more familiar themes of contemporary fiction. Devotion engages intelligently with such issues as hysteria, psychoanalysis, women's relationships, and the unreliability of memory and writing."

In non-fiction in "The Age", Barney Zwartz (religious editor) looks at The New Puritans: The Rise of Fundamentalism in the Anglican Church by Muriel Porter, which "Puts the heat on rich and powerful Sydney for the woes of Australian Anglicanism." Also reviewed is Memory, Moments and Museums: The Past in the Present edited by Marilyn Lake: "The concept of a 'national identity' is a spin-off of nationalism and has had a deadening effect on our historical commemorations."

It's a non-fiction weekend over at "The Australian" as well. Gideon Haigh's Asbestos House, about the James Hardie company, is reviewed by Ross Fitzgerald, who calls it "meticulously researched and powerfully written". The World According to Y by Rebecca Huntley "provides a breezy snapshot of a neglected generation"; and The New Puritans, see above.

John Wright profiles David Mitchell on the eve of the 170th anniversary of his birth. Mitchell was a renown collector of Australiana and his legacy was left to the State Library of NSW which created the Mitchell library in his honour. There would be a lot of us around who would envy Mitchell's financial freedom, which enabled him to buy whatever he liked, wherever he liked: 61,000 volumes in the end.

The Book Thief by Markus Zusak, which we href="http://www.middlemiss.org/weblog/archives/matilda/2006/02/worthy_books_un_24.html">looked at a week or so back, has been published in the US. Justine Larbelestier caught up with Markus in New York over the weekend to find that his novel, which was released on March 14 there, was featured on "Good Morning America" and subsequently hit #1 in Books on Amazon.

A check this morning finds that it has slipped from #3 yesterday to #8 today. Which is not too shabby anyway you look at it. Interesting to note that the book is considered Zusak's "breakout" novel here in Australia, after several young adult books, while the US edition looks to have a distinctly YA cover, and is listed as "Grade 9-up" by the "School Library Journal".

It was pleasant up the country, Mr. Banjo, where you went,

For you sought the greener patches and you travelled like a gent.,

And you curse the trams and 'busses and the turmoil and the "push,"

Tho' you know the "squalid city" needn't keep you from the bush;

But we lately heard you singing of the "plains where shade is not,"

And you mentioned it was dusty - "all is dry and all is hot."

True, the bush "hath moods and changes," and the bushman hath 'em, too --

For he's not a poet's dummy -- he's a man, the same as you;

But his back is growing rounder -- slaving for the "absentee" --

And his toiling wife is thinner than a country wife should be,

For we noticed that the faces of the folks we chanced to meet

Should have made a stronger contrast to the faces in the street;

And, in short, we think the bushman's being driven to the wall,

But it's doubtful if his spirit will be "loyal thro' it all."

Tho' the bush has been romantic and it's nice to sing about,

There's a lot of patriotism that the land could do without --

Sort of BRITSH WORKMAN nonsense that shall perish in the scorn

Of the drover who is driven and the shearer who is shorn --

Of the struggling western farmers who have little time for rest,

And are ruin'd on selections in the squatter-ridden west --

Droving songs are very pretty, but they merit little thanks

From the people of country which is ridden by the Banks.

And the "rise and fall of seasons" suits the rise and fall of rhyme,

But we know that western seasons do not run on "schedule time;"

For the drought will go on drying while there's anything to dry,

Then it rains until you'd fancy it would bleach the "sunny sky" --

Then it pelters out of reason, for the downpour day and night

Nearly sweeps the population to the Great Australian Bight,

It is up in Northern Queensland that the "seasons" do their best,

But its doubtful if you ever saw a season in the west,

There are years without an autumn or a winter or a spring,

There are broiling Junes -- and summers when it rains like anything.

In the bush my ears were opened to the singing of the bird,

But the "carol of the magpie" was a thing I never heard.

Once the beggar roused my slumbers in a shanty, it is true,

But I only heard him asking, "Who the blanky blank are you?"

And the bell-bird in the ranges -- but his "silver chime" is harsh

When it's heard beside the solo of the curlew in the marsh.

Yes, I heard the shearers singing "William Riley" out of tune

(Saw 'em fighting round a shanty on a Sunday afternoon),

But the bushman isn't always "trapping bunnies in the night,"

Nor is he ever riding when "the morn is fresh and bright,"

And he isn't always singing in the humpies on the run --

And the camp-fire's "cheery blazes" are a trifle overdone;

We have grumbled with the bushmen round the fire on rainy days,

When the smoke would blind a bullock and there wasn't any blaze,

Save the blazes of our language, for we cursed the fire in turn

Till the atmosphere was heated and the wood began to burn.

Then we had to wring our blueys which were rotting in the swags,

And we saw the sugar leaking thro' the bottoms of the bags,

And we couldn't raise a "chorus," for the toothache and the cramp,

While we spent the hours of darkness draining puddles round the camp.

First published in The Bulletin, 6 August 1892

Bulletin debate poem #4

(The second part of this poem will be published next week.)

| Wendy James OUT OF THE SILENCE Random House, 351 pp. Review by Perry Middlemiss |

Out of the Silence by Wendy James was released in October 2005 by Random House, and was, reportedly, the only Australian debut novel published by the company that year. As it happens they chose well - it's a good one.

The novel in set in Melbourne and country Victoria during the period of the late 1890s and early 1900s, a time of stifling social and political conservatism, sexual double-standards and rampant hypocrisy. Yet it was also a time when the women's suffrage movement was starting to organise and spread its message, a time when women were pushing back against the barriers imposed by men. It is against this background that the author has pitched the stories of Maggie Heffernan, Elizabeth Hamilton and Vida Goldstein, each of whom with ambitions beyond their perceived social standing.

Maggie Heffernan is a lively country working-class young woman whose life is the main thrust of the book. She becomes engaged to a local rake, but finds herself abandoned after she falls pregnant. The novel follows her grim journey from the country to the city, vainly seeking her ex-fiance, finding herself destitute and finally accused of a dreadful crime. Vida Goldstein is an educated single woman running a local private school, campaigning for votes for women and contemplating running for parliament. Elizabeth Hamilton lives in Vida's aunt's house in suburban Melbourne - an upper middle-class life that provides a sharp contrast with poor Maggie's circumstances. Elizabeth and Vida take up Maggie's cause after her arrest and while their efforts don't meet with total success, all characters are changed by the events within the book.

Elizabeth's story is told in a series of letters to her brother Robert, who lives in America, and in extracts from her journals. These alternate with Maggie's first-person narration of her own account. The easiest approach to this story would be to start at the beginning and to follow tight on Maggie's life-line, extracting every skerrick of pathos and anguish along the way, squeezing it dry of all emotion. But that's too simplistic a method to tell this tale properly and James rightly has taken the harder road and has achieved a better final product as a result.

There is an art to getting this narrative approach just right. Make the sections too short and the narrative loses its forward momentum, make them too long and the reader loses the thread of what is happening in the other plot-line and gets frustrated. This is a delicate balancing act that James maintains with some skill, adding newspaper clippings and even cutting Elizabeth's journal entries; to provide extracts of extracts, if you like. The effect is to increase the amount of white space on the page, reducing the heavy blocks of text so often found in "Victorian" novels, and thereby easing the reading experience in sections where setting and background information is provided. This exhibits a remarkable technique for a debut novel.

Beyond the writing technique we have a writer who is knowledgeable about the era in which the novel is set, yet who presents that research lightly. A lot of care appears to have been taken to present the right amount of background and scene-setting information without swamping the reader with too much detail. And yet a close-reading of the text will inform as well as entertain.

In the Author's Note, it is stated that the characters of Maggie Heffernan and Vida Goldstein are based on historical figures, while Elizabeth Hamilton is purely fictional. To this reader, the introduction of the character of Elizabeth is the component that allows the novel to reach its heights. The slow revealing of her own unfortunate history, including the miscarriage of the child she had conceived with a deceased lover, highlights the social injustices and hypocrisy suffered by Maggie. She also provides the link between Vida and Maggie, bridging the social and intellectual gaps between the characters. Without her the novel would have been a very different book indeed.

This is an accomplished work from a writer with the feel for the flow of a story, the capacity to see how to assemble disparate parts of a novel, and the ability to inhabit her characters fully. I look forward to her next work.

The shortlist for the 2006 National Biography Award has been announced.

"The National Biography Award was established in 1996 to encourage the highest standards of writing biography and autobiography and to promote public interest in those genres. The National Biography Award is administered by the State Library of New South Wales on behalf of the award's benefactors, Geoffrey Cains and Michael Crouch." - from the award website.

John Hughes: The Idea of Home: Autobiographical Essays (Giramondo Press)

William McInnes, A Man's Got to Have a Hobby (Hodder)

Alasdair McGregor: Frank Hurley: A Photographer's Life (Viking)

John Edwards: Curtin's Gift: Reinterpreting Australia's Greatest Prime Minister (Allen&Unwin)

Mary Ellen Jordan: Balanda: My Year in Arnhem Land (Allen&Unwin)

The prize is worth $20,000, and the winner will be announced on March 30th.

The longlist for the 2006 Miles Franklin Award has been announced with Victorian writers dominating the 12 novels.

Knitting, Anne Bartlett

The Garden Book by Brian Castro

The Secret River by Kate Grenville

An Accidental Terrorist by Steven Lang

The Ballad of Desmond Kale by Roger McDonald

Prochownik's Dream by Alex Miller

Sunnyside, Joanna Murray-Smith

A Case of Knives, Peter Rose

The Broken Shore by Peter Temple

Everyman's Rules for Scientific Living by Carrie Tiffany

Dead Europe by Christos Tsiolkas

The Wing of Night by Brenda Walker

The shortlist will be announced on 27th April, and the winner on June 22nd.

In "The Telegraph" Ali Smith reviews the new DBC Pierre: "Reading Ludmila's Broken English, the new novel from D.B.C. Pierre who won the 2003 Man Booker with his first novel, Vernon God Little, is like being hit over the head with a giant hammer, then hit again." Which gives you the impression she doesn't like it - then again maybe she has something about hammers. Anyway, the the review ends with telling you what else to expect, rather than making a definitive statement as to its worth: "Don't expect too high an art here. Don't expect a story. Expect the baroque. Expect slapstick and speed, funny and obscene, and a near-gorgeous overwrite out of which come occasional moments of shocking loss and beauty." Or did I miss something.

In the same paper, Tim Flannery considers The Devil's Picnic by Taras Grescoe, who "squanders the opportunity to

write an important book", and then has his own volume, The Weather Makers,

href="http://www.telegraph.co.uk/arts/main.jhtml;jsessionid=U5AMECKXCFQBLQFIQMFSFFOAVCBQ0IV0?xml=/arts/2006/03/12/bofla12.xml&sSheet=/arts/2006/03/12/bomain.html">reviewed by Susan Elderkin who finds that "what makes this book especially useful is its

multi-disciplinary approach".

Back home in "The Bulletin", James Bradley has a gander at the new Pierre: "Ludmila, for all its moral fury and flashes of genuine hilarity, is a curiously enervating experience. The book never quite knows when to stop, the characters possessed of a crazed loquacity which drowns out the wit which crackles between the lines"; Robin Wallace-Crabb reviews The Bone House by Beverley Farmer: "The book's four essays push language to that cliff edge, testing its ability to deal with all that a person's sensory equipment is receiving from life"; and Peter Pierce skims over Passarola Rising by Azhar Abidi and

Annabel Smith's A New Map of the Universe: "Both novels are confident performances, giving the perhaps illusory notion that foundations have firmly been laid for fictional excursions to come."

The longlist for the 2006 Miles Franklin Award will be announced tomorrow so I thought I might throw out a few suggestions for what might be on the list. Last year 43 novels were entered for the prize, with 12 making the longlist and five on the shortlist.

Possibilities:

Winter Journey by Diane Armstrong

Watershed by Fabienne Bayet-Charlton

The Garden Book by Brian Castro

Slow Man by J.M. Coetzee

The Patron Saint of Eels by Gregory Day

Grace by Robert Drewe

The Secret River by Kate Grenville

Surrender by Sonya Hartnett

Out of the Silence by Wendy James

Original Face by Nicholas Jose

Sandstone by Stephen Lacey

An Accidental Terrorist by Steven Lang

The Ballad of Desmond Kale by Roger MacDonald

Prochownik's Dream by Alex Miller

The Marsh Birds by Eva Sallis

The Broken Shore by Peter Temple

Everyman's Rules for Scientific Living by Carrie Tiffany

Affection by Ian Townsend

Dead Europe by Christos Tsiolkas

Road Story by Julienne van Loon

The Wing of Night by Brenda Walker

Which is a much longer list than I thought I'd end up with when I started this little exercise. There is always a bit of a problem chosing which books might appear on the shortlist due to the conditions of the award. In the past novels by authors such as Peter Carey have been deemed ineligible as they did not present an aspect of Australian life. It is also possible for non-Australian authors to be listed such as Matthew Kneale with his novel English Passengers. And let's not forget that Hannie Rayson was shortlisted for her play Life After George. As a consequence the following may, or may not, be deemed ineligible:

The Book Thief by Markus Zusak

And the following are pretty much certain to be omitted:

March by Geraldine Brooks

The Lost Thoughts of Soldiers by Delia Falconer

The God of Spring by Arabella Edge

Do I think I've covered it all? No, not a chance. There is bound to be some novel that pops up, a debut perhaps, that will sneak in under the radar. And a good thing too.

George Turner (1916 - 1997)

Walk a crowded street, see a hundred people in a minute. They are there, accepted, signifying nothing. Yet -- A stick swells with flesh, puts forth soul. At a subliminal warning eyes and brain communicate; you look at the face. It passes, anonymous as the wind, but a ripple has marked the mind. It could have been Joe who passed. You did not catch a breath or stare in his wake, but noticed him in a flicker of consciousness which did not quite emerge as, That one was different from the rest -- for an instant a person. He is not a big man, being slender and small-boned, but heavier and stronger than the casual glance might gather. There might have been a touch of the cat in him. Or the tiger ... even in stillness he suggested movement.

From A Waste of Shame by George Turner, 1965

Kate Grenville has been announced as the overall winner of the 2006 Commonwealth Writer's Prize for Best Book, for her novel The Secret River. The Best First Book Award went to Mark McWatt from Guyana for Suspended Sentences: Fictions of Atonement.

There I was, just the other day, stating that the new Carey novel, Theft, wouldn't be out until June, and then I read in Maud Newton's weblog that it's already been published here in Australia. Bugger.

From the publisher's blurb: "A truly brilliant novel - an act of fantastic writing bravura from Peter Carey, in which he once again displays his extraordinary flair for language - THEFT is a love poem of a completely unexpected kind. Ranging from the rural wilds of Australia to Manhattan via Sydney and Tokyo and exploring the ideas of art, fraud, responsibility and redemption, this is a dark, thought-provoking and stirring story that will also make you laugh out loud." Yeah, I'd read that.

For a good overview of what was on offer at the 2006 Adelaide Writers' Week have a look at the ABC blog Articulate.

Having the resources of the ABC on hand makes life a lot easier. Kerryn Goldsworthy also provides her wrap-up of the week on her weblog. She partly laments the fact that the festival was in her home town: it's good that it's cheap to get to, but you can't get away from the mundane parts of your non-festival life.

Carl Zimmer reviews Tim Flannery's new book The Weather Makers in "The New York Times", in concert with Field Notes From a Catastrophe by Elizabeth Kolbert. Both books are considered "important" and "Their books do not merely satisfy scientific curiosity. Whatever their flaws, with any luck they may help force us to take more responsibility for our collective actions." This comes on top of the recent book launch at St Paul's in London, which also featured a talk by David Attenborough.

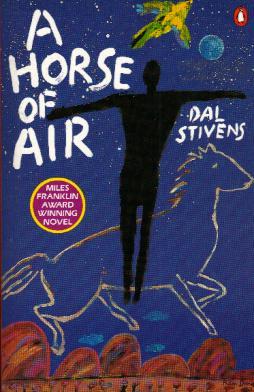

A Horse of Air by Dal Stivens, 1970

(Penguin 1986 edition)

Cover illustration by Ken Done

This novel won the 1970 Miles Franklin Award

James Bradley's The Resurrectionist is reviewed by Peter Pierce in "The Age" this week. Pierce is professor of Australian literature at James Cook University and generally I find his reviews perceptive and informative. In this case I'm more than a bit bemused. Bradley's novel is set among the anatomists of 1820s London and the men who supply them with corpses, the resurrectionists. Pierce states early: "Begun with such confidence in the command of its prose, Bradley's novel becomes more commonplace, gloomy and ghoulish as it details the robbing of graves or the purchase of cadavers, matter-of-fact about a business that can depend on murder...Curiously, this is a novel with its own ringing descriptive voice but only an uneasy authority over its subject." I have no idea what he means by this. The "descriptive voice" I understand, but why the next phrase? Pierce then seems to imply in the same paragraph that Bradley uses stock-standard gothic stereotypes, which doesn't doesn't really fit with subject authority. It's something else entirely, and, I might say, not one that I agree with.

I think also that Pierce is not sure how to approach this work. After Swift's fall into "despair and destitution" Pierce feels that "Bradley narrative pace slackens". As he says, "one act of treachery follows another" as Swift's sense of self-worth is slowly and inevitably destroyed. Pace isn't important here surely. What we are after is a description of a human personality slowly coming apart at the seams, and the pace of the book needs to reflect that.

In the end Pierce concludes: "This is still the work of a strong talent, a writer whose ambition magnifies the structural problems of his work, who sought here rather to struggle with the challenge of previous historical fictions, than more comfortably to seek space for his own." I don't know what "previous historical fictions" he's talking about here. Pierce doesn't mention them.

In her review of Safety by Tegan Bennett Daylight, Michelle Griffin finds the author has taken a big literary risk: "this novel reads like it was written according to some puritan artistic code; all natural lighting, unresolved tensions and characters who can't escape the basic parameters of their personalities. Although Safety is difficult to warm to, it has plenty of integrity, refusing all temptations to pander to the usual resolutions of love stories." And she concludes that "Although this is a novel about people who love each other, it is not, in any sense, a romantic novel."

Geoffrey Blainey describes Hirst as "one of the nation's most independent and original historians" so a collection of his essays is of some importance. Actually, any collection of essays by any Australian historian is of importance in this era of "the history wars". Morag Fraser reviews his latest collection, Sense & Nonsense in Australian History, in "The Age" and finds that there "is vigour in Hirst's essays, a plain man's passion, you could call it. He will say what he means. To what end? Sometimes he reads like a reflex contrarian, but, more often, like a deft scholar whose researches leave him uneasy with orthodoxies, out of kilter with the historical fashion of the moment, but leave us informed."

John Hirst's essay collection is also reviewed in "The Weekend Australian" by Robert Murray, who concludes "The book should be essential reading for those who want to ponder, let alone write and teach about, Australian history but fear choosing between the Paul Keating/Phillip Adams view on the one hand and Pauline Hanson or David Flint on the other."

Phil Brown considers Shadowboxing, a first novel by Tony Birch: "Birch's descriptions of the lower socio-economic world of inner Melbourne in the '60s are brilliant and he evokes, with a curious nostalgia, a claustrophobic world that anyone would be lucky to escape from unscathed. He has a great ability to pare down his prose, laying bare the raw flesh of the matter in the process. Despite their rigours, the stories are engaging, with flashes of larrikin humour. The book is even something of a page-turner at times, although the calamity of one page often leads only to heartbreak on the next."

I'm wonderin' why those fellers who go buildin' chipper ditties,

'Bout the rosy times out drovin', an' the dust an' death of cities,

Don't sling the bloomin' office, strike some drover for a billet

And soak up all the glory that comes handy while they fill it.

P'r'aps it's fun to travel cattle or to picnic with merinos,

But the drover don't catch on, sir, not much high-class rapture he knows.

As for sleepin' on the plains there in the shadder of the spear-grass,

That's liked best by the Juggins with a spring-bed an' a pier-glass.

An' the camp fire, an' the freedom, and the blanky constellations,

The 'possum-rug an' billy, an' the togs an' stale ole rations --

It's strange they're only raved about by coves that dress up pretty.

An' sport a wife, an' live on slap-up tucker in the city.

I've tickled beef in my time clear from Clarke to Riverina,

An' shifted sheep all round the shop, but blow me if I've seen a

Single blanky hand who didn't buck at pleasures of this kidney,

And wouldn't trade his blisses for a flutter down in Sydney.

Night-watches are delightful when the stars are really splendid

To the chap who's fresh upon the job, but, you bet, his rapture's ended

When the rain comes down in sluice-heads, or the cuttin' hailstones pelter,

An' the sheep drift off before the wind, an' the horses strike for shelter.

Don't take me for a howler, but I find it come annoyin'

To hear these fellers rave about the pleasures we're enjoyin',

When p'r'aps we've nothin' better than some fluky water handy,

An' they're right on all the lickers -- rum, an' plenty beer an' brandy.

The town is dusty, may be, but it isn't worth the curses

'Side the dust a feller swallers an' the blinded thirst he nurses

When he's on the hard macadam, where the jumbucks cannot browse, an'

The wind is in his whiskers, an' he follers twenty thousan'.

This drovin' on the plain, too, it's all O.K. when the weather

Isn't hot enough to curl the soles right off your upper leather,

Or so cold that when the mornin' wind comes hissin' through the grasses

You can feel it cut your eyelids like a whip-lash as it passes.

Then there's bull-ants in the blankets, an' a lame horse, an' muskeeters,

An' a D.T. boss like Halligan, or one like Humpy Peters

Who is mean about the tucker, an' can curse from start to sundown,

An' can fight like fifty devils, an' whose growler's never run down.

Yes, I wonder why the fellers what go buildin' chipper ditties

'Bout the rosy times out drovin' an' th' dust an' death of cities,

Don't sling the bloomin' office, strike ole Peters for a billet,

An' soak up all the glory that comes handy while they fill it.

First published in The Bulletin, 30 July 1892

Bulletin debate poem #3.

Benedicte Page, of The Bookseller, has published an interview titled "Peter Carey: Fakes, Frauds, Lies and Hoaxes". Carey talks about his upcoming novel Theft: A Love Story (due from Faber in June), James Frey, and the place of Australia in the literary pantheon: "There is this whole issue for Australia of being on the periphery and having no cultural authority, of cultural authority being determined elsewhere--in New York or in

London--and Australians have taken huge pleasure in undermining that authority and proving it wrong."

And about the prospect of returning home: "I've followed my life--one follows it, not makes it--and my ex-wife really, really wanted to come and live here. I would never have thought of coming in a million years but there was no reason not to, so that happened...yes, a time will come to go back to Australia. I'm on a kind of moral holiday."

[Thanks to The Literary Saloon for the heads-up.]

Publishers Allen and Unwin have announced that the 2006 Australian/Vogel Literary Award is now open, and that entries are now being accepted. The entry form can be found on their award webpage. Be aware that the entry form is a PDF File.

The award is for an unpublished manuscript (novel or non-fiction) by a young Australian writer, and is worth $20,000 plus royalties to the winner. The winner gains a guarantee of publication. It is not unusual for runners-up to be published as well. Entrants must normally be a resident of Australia and under the age of 35 years on 31 May 2006, ie born after 31 May 1971. Entries must be lodged, accompanied by the offical entry form, by 31 May 2006.

The 2006 John O'Brien Bush Festival will be held from 15th-19th March in Narrandera in the NSW Riverina. Events will feature bush poetry, humour and music. This festival was a winner in the NSW Inland Tourism Awards in both 2004 and 2005. You can get a taste of O'Brien's poetry in his book Around the Boree Log and Other Verses.

After last week's profile of Marshall Browne, we have James Hall's review of his new novel, Rendezvous at Kamakura Inn, in "The Sydney Morning Herald": "In crisp, emphatic sentences, he draws credible, well-motivated characters and describes abrupt, explosive action with no sense of self-indulgence. In an unusual career for a writer, Browne, once a banker, has also been a commando and a paratrooper. He obviously knows about violence."

Sandra Hall, a film reviewer for "The Sydney Morning Herald", has written her second novel which is found somewhat wanting by Bronwyn Rivers in the same paper. "Given Hall's professional knowledge of narrative technique it is rather surprising that she falls into the biggest trap for young players: too much telling and not enough showing...This novel makes vivid its historical setting, yet its early drama dies away." A different approach to some British papers who only seem to want

favourable reviews of books by staff.

We had the Madonna book show, and now, it appears, Kylie Minogue is going to follow suit by writing a children's book for Puffin.

Now, I've got nothing against Kylie, she does her job well and I've been impressed with her staying power over the years, but an author? I wonder if she'll do a Stephen King and ask for a $1 advance against royalties. I somehow doubt her management would have a bar of that. It'd be a good gesture though, and show she is at least confident about her work.

The piece in "The Age" is reprinted from "The Guardian".

As James Bradley's new book The Resurrectionist is about to be launched at the Adelaide Writers' Week, Jason Steger has profiled him in "The Sunday Age". The novel, a gothic journey from the light into the dark and back again partly inspired by the story of Edinburgh's William Burke and Robert Hare, took Bradley to some strange places: "I'm so glad I'm not writing the book any more . . . in all honesty I think it messed with my head". Originally scheduled for publication in 2001, it seems the author embarked on a journey almost as dark as the one his main character endures.

[As I write I'm about half-way through the novel, so I think the word "enjoy" is not one I should use about it at this point. The sense of foreboding is rather intense and fifty pages is about all I can handle at a sitting. This is one that is going to stick in the mind for some time to come.]

Jason Steger, literary editor of "The Age", provides what I hope is a running commentary on the 2006 Adelaide Writers' Week. He attends panels/talks by the likes of David Malouf, Sarah Waters, Val McDermid, Vikram Seth, Delia Falconer and Gail Jones.

Over on her weblog, A Fugitive Phenomenon, Kerryn Goldsworthy makes up for missing J.M. Coetzee's citizenship ceremony (tsk, tsk)

by writing a personal account of the first two days of the event. She doesn't attempt to get to everything, skipping Vikram Seth's event due to the long lines of punters waiting to get in, and as a result produces a piece that provides a much better

view of what it's like to attend and participate. If the two of these continue, you'll get a combination of "commercial" and "personal" accounts of the event which complement each other quite nicely.

[By the way, can someone at "The Age" get another photograph of Gail Jones? There must be one somewhere. The image published today is about worn out I reckon.]

|

Charles Harpur (1813 - 1868)

Not a bird disturbs the air!

There is quiet everywhere;

Over plains and over woods

What a mighty stillness broods.

Even the grasshoppers keep

Where the coolest shadows sleep;

Even the busy ants are found

Resting in their pebbled mound;

Even the locust clingeth now

In silence to the barky bough:

And over hills and over plains

Quiet, vast and slumbrous, reigns.

Only there's a drowsy humming

From yon warm lagoon slow coming:

'Tis the dragon-hornet - see!

All bedaubed resplendently

With yellow on a tawny ground -

Each rich spot nor square nor round,

But rudely heart-shaped, as it were

The blurred and hasty impress there,

Of vermeil-crusted seal

Dusted o'er with golden meal:

Only there's a droning where

Yon bright beetle gleams the air -

Gleams it in its droning flight

With a slanting track of light,

Till rising in the sunshine higher,

Its shards flame out like gems on fire.

Every other thing is still,

Save the ever wakeful rill,

Whose cool murmur only throws

A cooler comfort round Repose;

Or some ripple in the sea

Of leafy boughs, where, lazily,

Tired Summer, in her forest bower

Turning with the noontide hour,

Heaves a slumbrous breath, ere she

Once more slumbers peacefully.

O 'tis easeful here to lie

Hidden from Noon's scorching eye,

In this grassy cool recess

Musing thus of Quietness.

The longlist for the 2006 Orange Prize for Fiction has been announced and a few Australian books have made the grade. Included are: Dreams of Speaking by Gail Jones, and Everyman's Rules for Scientific Living by Carrie Tiffany.

The shortlist for the award will be announced on 26th April. The New Writers award shortlist will be announced on 3rd May. The Awards ceremony will be held on 6th June.

Tim Flannery, author of The Weather Makers and Director of the South Australian Museum in Adelaide, reviews the following books for the "New York Review of Books": Life in the Undergrowth by David Attenborough, The Smaller Majority: The Hidden World of the Animals that Dominate the Tropics by Piotr Naskrecki, and Locust: The Devasting Rise and Mysterious Disappearance of the Insect that Shaped the American Frontier by Jeffrey A. Lockwood.

"By the late twentieth century fascination with the minuscule had begun to pall, and now it takes an exceptional book indeed to reawaken our interest. Thankfully, in David Attenborough's Life in the Undergrowth, Piotr Naskrecki's The Smaller Majority, and Jeffrey Lockwood's Locust we find three works that do so."

[Update: I got a bit confused earlier and listed "Richard" Attenborough rather than "David" as the author of one book under review. This was pointed out by an anonymous commenter who stated: "Life in the Undergrowth by Richard Attenborough. That would be the grubs of Hollywood. It's Dave, not Dicky, but you already knew that." It's the

Oscar season that's to blame, I reckon.]

As foreshadowed last week, J.M. Coetzee took Australian citizenship yesterday in a ceremony at the Adelaide Writers' Week. Coetzee was sworn in by Federal Immigration Minister Amanda Vanstone in front of some 200 people, including Cornelia Rau - falsely detained by immigration officials last year. Would have been interesting to see the minister's face when she noticed Ms Rau. I would have paid good money for that. Kerryn Goldsworthy has indicated that she intends to post about this ceremony on her weblog. It's not there yet, so we'll just keep gently prodding.

The winners of the 2006 Adelaide Festival Awards for Literature have been href="http://www.arts.sa.gov.au/site/page.cfm?area_id=10&content_id=64">announced.

$10,000 South Australian Premier's Award for Literature

Sixty Lights by Gail Jones (Vintage)

$15,000 Award for Children's Literature (143 entries)

It's Not All About You, Calma! by Barry Jonsberg (Allen & Unwin)

$15,000 Award for Fiction (114 entries)

Sixty Lights by Gail Jones (Vintage)

$10,000 Award for Innovation (22 entries)

<More or Less Than> 1-100 by MTC Cronin (Shearsman Books)

$15,000 Award for Non-Fiction (154 entries)

Velocity by Mandy Sayer (Vintage)

$15,000 John Bray Poetry Award (90 entries)

Totem by Luke Davies (Allen and Unwin)

$10,000 Jill Blewett Playwright's Award for the Creative Development of a play script by a South Australian Writer (8 entries)

This Uncharted Hour by Finegan Kruckemeyer

$10,000 Award for an Unpublished Manuscript by a SA Emerging Writer to be Published by Wakefield Press (32 entries)

The Quakers by Rachel Hennessy

$15,000 Barbara Hanrahan Fellowship (7 entries)

Mike Ladd

$15,000 Carclew Fellowship (6 entries)

Christine Harris

[Thanks to Wendy James for the notice.]

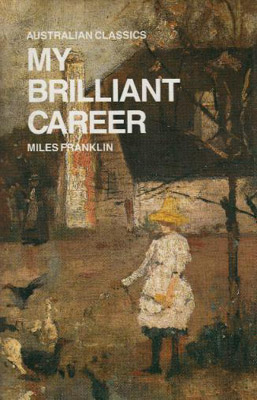

My Brilliant Career by Miles Franklin, 1954

(Angus & Robertson 1986 edition)

The cover: Tea Time by Charles Condor, 1888

Adelaide Writers' Week kicked off over the weekend, and, to celebrate, "The Age" has published Kate Llewellyn's love letter to the event. Held every two years since its inception in 1962, Writers' Week has grown from a lecture at the University of Adelaide to 4 marquees on the banks of the River Torrens, and Llewellyn has been to all of them. There's a lot of name-dropping in the piece but this is only to be expected at an author-driven event, and anyway Llewellyn carries it off with such charm you just go with the flow.

A feeling of complete joy comes over me as I walk down North Terrace on the way to the tents. The day stretches ahead and there is nothing but pleasure to look forward to.Wherever I am I make sure that I am back in Adelaide in time for Writers' Week. Year after year, weaving through the growing crowds in the hot autumn air, choosing seats under trees or umbrellas, meeting friends, long lunches in a bistro by the Torrens; it has gone on for 44 years.

Young hirsute men have grown into gentlemen with comb-overs who still attend. (Why won't they cut their hair?) We pregnant girls are grandmothers. I am one of the diminishing number who have never missed a Writers Week. Nor will I, I hope, until I fade like a dust mote floating from a tent into the autumn air.

DBC Pierre's second novel Ludmilla's Broken English is reviewed in "The Age", but the piece isn't on the website. I suspect you'll be seeing a lot of this book over the next week or so. Australian novels normally get about 3 weeks in the spotlight here, then it's "back to the garret for you boyo". James Ley finished his review with: "Can't wait for the third novel and a Triumphant Return to Form." Yeah, righto James. Just keep taking the tablets, all right?

M.J. Hyland had a bit of a hit with her first novel, and now presents the difficult follow-up. Gregory Day is impressed: "Carry Me Down is a heartrendingly domestic work full of compassion for the most ordinary of our human frailties, as parents, as children, as precocious solo flyers in the defiantly gravitational airs of life and as mediocre family groups stuck within our own blood dialects."

In "The Weekend Australian", Graeme Blundell profiles Australian crime writer Marshall Browne, best known for his Inspector Anders novels. The author has recently delivered the third in this series to his publisher as well as Rendezvous at Kamakura Inn, described as "a violent locked-door mystery set in a frozen Japanese retreat haunted by yakuza assassins." This looks like turning into a new series, as does his character Franz Schmidt in The Iron Heart, who previously appeared in The Eye of the Abyss in 2002. Keeping three series on the go will be a bit of a struggle but it will certainly keep the author busy.

Cath Kenneally reviews M.J. Hyland's Carry Me Down and tends to get a bit carried away I feel, invoking Salinger for Hyland's first novel, and Faulkner and James Joyce for this one. The kiss of death perhaps?

Pandanus Books is best known as a publisher of non-fiction titles dealing with the Pacific Rim and South-East Asia. Lately it has been branching out into fiction and its latest offering is Venom by Dorothy Horsefield. Lon Bram is quite taken with the book referring to it as a "gem".

There's also a review of the new DBC Pierre, and two collections of poetry given the once over by Barry Hill.

(On reading Henry Lawson's "Borderland")

So you're back from up the country, Mister Lawson, where you went,

And you're cursing all the business in a bitter discontent;

Well, we grieve to disappoint you, and it makes us sad to hear

That it wasn't cool and shady -- and there wasn't plenty beer.

And the loony bullock snorted when you first came into view;

Well, you know, it's not so often that he sees a swell like you;

And the roads were hot and dusty, and the plains were burnt and brown,

And no doubt you're better suited drinking lemon-squash in town.

Yet, perchance, if you should journey down the very track you went

In a month or two at furthest you would wonder what it meant,

Where the sunbaked earth was gasping like a creature in its pain

You would find the grasses waving like a field of summer grain,

And the miles of thirsty gutters blocked with sand and choked with mud,

You would find them mighty rivers with a turbid, sweeping flood;

For the rain and drought and sunshine make no changes in the street,

In the sullen line of buildings and the ceaseless tramp of feet;

But the bush hath moods and changes, as the seasons rise and fall,

And the men who know the bush land -- they are loyal through it all.

But you found the bush was dismal and a land of no delight,

Did you chance to hear a chorus in the shearers' huts at night?

Did they "rise up, William Riley" by the campfire's cheery blaze?

Did they rise him as we rose him in the good old droving days?

And the women of the homesteads and the men you chanced to meet --

Were their faces sour and saddened like your "faces in the street,"

And the "shy selector children" -- were they better now or worse

Than the little city urchins who would greet you with a curse?

Is not such a life much better than the squalid street and square

Where the fallen women fluant it in the fierce electric glare,

Wehere the sempstress plies her sewing till her eyes are sore and red

In a filthy, dirty attic toiling on for daily bread?

Did you hear no sweeter voices in the music of the bush

Than the roar of trams and 'busses and the war-whoop of "the push"?

Did the magpies rouse your slumbers with their carol sweet and strange?

Did you hear the silver chimng of the bell-birds on the range?

But, perchance, the wild birds' music by your senses was despised,

For you say you'll stay in townships till the bush is civilised.

Would you make it a tea-garden and on Sundays have a band

Where the "blokes" might take their "dionahs" with a "public" close at hand?

You had better stick to Sydney and make merry with "the push,"

For the bush will never suit you, and you'll never suit the bush.

First published in The Bulletin, 23 July 1892

Bulletin debate poem #2.

| Reviews of The Patron Saint of Eels by Gregory Day. |

Description: "A contemporary fable, this book shows that when life seems dull and cruel it is the power of the natural world, and our ability to imagine it, that can bring the wonder back into living.

"In the southern Italian village of Stellanuova, in the 1700s, a Franciscan monk, Fra Ionio, becomes known as the Patron Saint of Eels when he brings a distraught fisherman's yearly catch of eels back from the dead in the village market. When Stellanuova's inhabitants emigrate to Australia in the post World War II migrations of the 1940s, 50s and 60s, the immortal saint is left looking down on an abandoned town. To fulfil his calling, he decides in heaven to migrate with his countrymen and now looks down on the state of Victoria, where he intercedes in matters relating to eels.

"In the southern Victorian town of Mangowak, Noel Lea lives with the melancholy inheritance of a place undergoing the gentrifications of contemporary Australia. Along with his oldest friend, Nanette Burns, he longs for a time when life was less complex and unexpected magic seemed to permeate the ocean town and its people. When spring rains flood a nearby swamp and hundreds of eels get trapped in the grassy ditches around Noel's family home, he and Nanette encounter the vibrant Fra Ionio and get more magic than they bargained for."

In "Australian Book Review", Sarah Kanowski finds a lot to like with the novel but then determines that the author's approach may be a limiting factor: "Gregory Day depicts a country world of pub yarns, simple happiness and a deep, if unarticulated, connecton to the land. Its heroes are old bush characters still in possession of 'that vast and intimate family knowledge born out of the gifts of improvisation and bushcraft, of getting by.' The rendering of everyday speech is not easy, and Day handles its blunt cadences well. However, a perception of the world that is dominated by telling silences necessarily falters when called on to articulate the miraculous".

On the other hand, Lisa Gorton in "The Age" doesn't have the same problems: "Day is a musician as well as a writer and The Patron Saint of Eels is composed like music, with a pattern of recurring phrases and images that carry his theme in different keys. In this way, it is a highly deliberate work, with its depths all brought to the surface, as it were. If this extreme clarity is to some extent the novel's limitation, it is also part of its charm. For it is the self-consistency of Day's style and theme that allows him to bring together so many quirky and various things: comical accounts of local characters and pious reflections on the meaning of landscape; Mangowak history and the story of how a Franciscan monk in the southern Italian village of Stellanuova became the Patron Saint of Eels."

In the Australian, Liam Davison is quite impressed with the work: "In [this] wonderful first novel, the enigma of the eel becomes the central metaphor for the charming contemporary fable about migration and belonging, and mortality and belief." Which, on the face of it, seems to stretch the bonds of credibility somewhat. But Davison is a major novelist himself so he knows where a reader might be a little dubious: "In another writer's hands, this quasi-religious fable with its veiled social and environmental agenda might have tested the credulity and goodwill of its readers. Day, though, understands the power of the story and the way local mythology and folklore invests a place with its own magic."

Michelle Griffin profiles the author in "The Age".

In "The Bulletin", Barry Oakley looks at James Bradley's The Resurrectionist and considers that: "Like [the anatomist] exposing layer after layer in his quest for the secret of life, Bradley pushes past the blood and gore in a search for the secret of identity." We also have the "transcends the genre" phrase in the review. Not one I'm keen on, as it comes across as condescending. I don't think Oakley meant it that way but grumpy old bastards like me tend to look for stuff like this.

Also, at the same webpage, Salley Blakeney reviews M.J. Hyland's second novel Carry Me Down, which turns out to be "a page turner -- a gripping story told so well that it changes the way you see things. M.J.Hyland has the potential to be an Irish literary artist, not one of the blarney gang." And Judith White looks at Tegan Bennett Daylight's novel Safety and finds: "This is a young writer who more than fulfils her early promise. Ten years after her first book, Bombora, the writing is still fresh, elegant and precise. And now her canvas is expanding, her characters gaining depth. May she continue to take her time; her work is worth waiting for."

In "The Age", James Ley reviews the novel Rifling Paradise by Jem Poster: "There are indications that Poster has the capacity to be an accomplished stylist, but his dialogue is as mawkish and wooden as that of any soap opera. This would be less of a problem if he did not force the dialogue to carry so much of the burden of exposition...Rifling Paradise is, nevertheless, a readable and well-paced novel, but one which is, for all it good intentions, rather unremarkable."

Christoper Bantick is impressed with Sara Douglass's new novel Darkwitch Rising, the third volume in her Troy Game series. "Douglass's feel for character melds real time with imagined place most felicitously. With an assured narrative voice and animated characters - who quickly begin to matter to us as people - Darkwitch Rising is a book that will please Douglass's established audience. It also deserves to win new readers."

Andrew Reimer thinks DBC Pierre's novel Ludmilla's Broken English is "weird and wonderfully outrageous". So the verdicts on this are going to be widely spread it seems.

Jason Steger, in "The Age", reports that writers in Victoria will this year vie for the richest literary prize in Australia. "The annual Melbourne Prize, which was awarded last year for urban sculpture, is focusing this year on writing. It will give $60,000 to one writer in recognition of a body of work, $30,000 to a writer under 40 for "best writing", and a $3000 "people's choice" prize to the finalist who gets the most votes from the public." Considering that the Miles Franklin award carries a prize of $42,000 and the various state literary awards range from $15,000 to $25,000, this is a major prize indeed. Entries open on May 15 and close on July 14. Finalists will be announced in September and the winners on November 15.