|

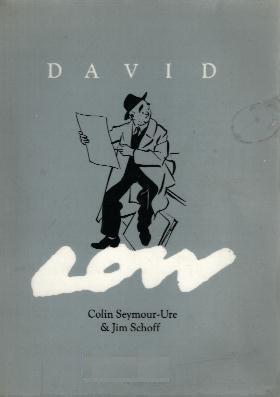

David Low Colin Seymour-Ure and Jim Schoff 1985 |

|

Dustjacket synopsis: From precocious beginnings in his native New Zealand, through the war years on Beaverbrook's Evening Standard to his final work for the Guardian, Low's skill in capturing the spirit of his time was undisputed. Politicians courted or damned him, Hitler and Mussolini banned him, but nobody could ignore this brilliant pictorial journalist who drew his leading articles instead of writing them and influenced a whole generation of cartoonists on both sides of the Atlantic. Such characters as the immortal Colonel Blimp and the TUC carthorse are stamped on the nation's consciousness, and Low's now classic portrait caricatures for the New Statesman are widely sought by collectors. In this, the first full-length appreciation of Low's life and work, Colin Seymour-Ure provides a fascinating account of the artist's technique, attitudes and impact and presents, with Jim Schoff, a selection of over 150 of his very best illustrations, drawing on archive material and persona1 sketchbooks hitherto unavailable and including a number of cartoons considered too controversial to publish in their day. Low liked to call himself 'a nuisance dedicated to sanity'. This book is a tribute to a critical but constructive spirit. First Paragraph from the Introduction: Sir David Low - he accepted a knighthood in 1962 - was the most celebrated cartoonist of his age. He was born in New Zealand on 7 April 1891 and died in London on 19 September 1963. He was an established success on the Bulletin in Australia by his mid-twenties and on the London evening Star before he was thirty. Lord Beaverbrook coaxed him to the Evening Standard in 1927, and there he displayed a mastery of his art for more than twenty years. From 1950 to 1953 he worked on the Daily Herald and then for ten years, before his death, the Manchester Guardian. On the great international issue of the 1930s - the rise of European Fascism - he was triumphantly and tragically correct. More generally, he observed events from a left-of-centre vantage point; but he was never extreme enough, in opinion or style, to lose touch with his large (mainly middle-class) audience or to seem strident and predictable. On the contrary, he expressed with great skill the conventional wisdom of the day - for purposes, more often than not, of challenging it. Whatever the issue, domestic or foreign, Low's mockery helped his contemporaries, and can help us still, to understand the attitudes he criticised as well as those he shared. Later generations are bound to lose many of the nuances and associations of his cartoons. None the less he has surely fixed, more than anyone else, the lasting image of Hitler and Mussolini. In Colonel Blimp, too, he created an image of reactionary stupidity which has taken on a life of its own. ('Gad, Sir! Baldwin may have no brains, but he's a true Englishman.') People who look blank at the name Low will smile in recognition at the name Blimp. From the Seeker & Warburg paperback edition, 1985. |